详细剧情

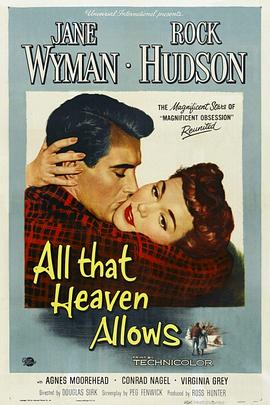

Cary Scott(简·怀曼 Jane Wyman 饰)虽然是一个有着两个孩子的中年寡妇,身边却依然不缺追求者。一天她在自己的花园里邂逅了新来的园丁,已故的老园丁的儿子——年轻的Ron Kirby(罗克·赫德森 Rock Hudson 饰)。几次接触后,Cary了解到Ron对于种植的喜爱,于是Ron带着Cary去了他的家。年龄的差距并不能阻止两人坠入爱河,然而他们的爱情却要面对许多考验。首先提出反对的是Cary的儿子和女儿,她的儿子甚至以离家出走来威胁母亲放弃这段关系。而当整个镇上都充满了关于两人的流言蜚语时,Cary也感到了巨大的压力。她试着带上Ron去参加俱乐部的派对,却遭遇了一些不快的事情。Cary还是选择了和Ron分开,但两人却还是爱着对方......

长篇影评

1 ) 喜欢视觉呈现,不喜欢故事

Several memorable lines: "security comes from inside himself,” “home is where you are,” “you are running away from something important because you are afraid,” and etc.

Carefully designed costumes and props. The film starts with Sarah, wearing a bright blue dress, stepping out of her richly blue car. The color choice is, first, visually attractive and, second, speaks of her extroversive personality. Later, the rather casual clothes of Ron’s friends at the dinner contrast with the exquisite suits and dresses in the cocktail party of Cary’s friend. The costumes highlight the stark difference between the circles of Ron and Cary, indicating their different social positions and life styles. Cary's different outfits throughout the film are also carefully chosen. She starts from a widow's grey suit. After meeting Ron, she puts on a vibrantly red dress for the country club. She shift back to the widow's black velvet on Christmas Eve after breaking up with Ron. These all suggest Cary's mental activities.

Some hints are given to foreshadow later developments in the story. At first is the branch that Ron gave to Cary, which she treated like a bouquet of flowers and placed in a beautiful vase. The second is the broken Wedgwood porcelain. Other elements are used to indicate the ideology of the film. An example would be the book, Walden, that Cary picked up at the Andersons'.

The curated lighting is my favorite element of this film. It uses high-key lighting in the garden scene and the party scene to create more realistic settings. Low-key lighting, on the other hand, is used in more emotionally charged scenarios. For the conversations between Cary and Ron and Cary and her son, high contrast of light and darkness hides and reveals the facial expressions of the characters. The most memorable scene for me is when Ron and Cary stand in front of the large glass window. The cold and blue lights from the snow outdoors juxtaposed with the warm and orange lights of fireplace illuminating behind the couple generate such a peaceful yet secretly melancholy atmosphere. This also foretells the following warm proposal and cold conflict.

2 ) 随想

《深锁春光一院愁》: 完成度非常高,台词设置精巧,画面色彩鲜明。 这么忧伤动人的剧情,带来的艰难与抉择堪比初三时看《罗马假日》。看了一点后意识到启发了托德海因斯的《远离天堂》。但远离天堂似乎才是现实,没有happy ending. 中产阶级妇女都爱园丁。洛克哈德森的脸简直了,完美得跟雕塑一样。这张脸自高三起一直贴在我屋子,某期《看电影》杂志里的小海报。 和《蔚蓝深海》一样,医生都扮演知心大哥的角色:因为逃避,所以头痛。你甚至比过去更加孤独。你高尚的牺牲有什么意义呢。如果他真爱我,他会来找我的。不!你要是爱他,你该去找他!You are ready for a love affair,but not for love. 要是坐在电影院大银幕前,定会在光影之中泪流满面吧。 It won't be easy时甚至想起John and Yoko. 经典台词: 有你在的地方就是家。你回家来了。 多少人都生活在平静的绝望中。 She doesnt want to make her own mind,no girl does.She wants you to make up for her. ironic:1.女儿满嘴弗洛伊德,研究社会学心理学,分析各种案例。看起来很先锋很自由,说寡妇不该被埋葬,这又不是古埃及,要活出自我,不在乎别人的想法。但到自己身上就行不通了。是个彻底的理论派。 罗恩是彻底的行动派。这是罗恩的bible吗。不,罗恩的bible就是活出自我。他从来不会让不重要的东西变得重要。活出真正的自我。安全感源于自我,无法被带走。VIP-very independent person. 2.电视机。孤独的老女人最后的避难所。只要轻轻旋转按钮,戏剧,喜剧,生活,就在你的指缝中展开。 关于什么是自私,什么是活出自我,究竟如何判定。自私不过是忠于内心的另一种表达方式。 儿女、罗恩哪个不自私呢。上一秒他们还说你自私,下一秒你无私了,你的无私就恰恰被他们的自私所利用。 鹿 很多事情答案很简单,但你要用很久才可以想明白。那不是一夜就能figure out的。

3 ) All That Heaven Allows: An Articulate Screen by Laura Mulvey

Douglas Sirk once said: “This is the dialectic—there is a very short distance between high art and trash, and trash that contains an element of craziness is by this very quality nearer to art.” When All That Heaven Allows was released by Universal Pictures in 1955, it was just another critically unnoticed Hollywood genre product, designed to appeal to the trashy “women’s weepie” audience. Now, in retrospect, it is considered to be closer to the art side of Sirk’s dialectic, and one of his key films. But this is part of a wider process of critical reevaluation in which his entire body of work has been rediscovered and reappraised by successive generations of filmmakers and historians.

No one seeing the film at the time of its release would have imagined its director to be an elegant, extremely erudite European whose career started in the theater of Weimar Germany and who was an early director of Bertolt Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera. After a short but successful career at UFA studios in the vacuum left by the massive emigration of Jewish talent after the Nazis came to power in 1933, Sirk made his way to Hollywood, directing his first film there in 1942. Following an unsuccessful attempt to return to Germany in 1949–50, he signed a contract with Universal. His movie career then culminated with his highest-profile films, the melodramas of 1952–58. By 1959, he was Universal’s most successful director. At that very moment, he left moviemaking and America. Until his death in 1987, he and his wife, Hilde, lived in Lugano, Switzerland.

All That Heaven Allows marks the final turning point in Sirk’s strange and varied career. On the back of Magnificent Obsession’s success the previous year, Universal gave him a budget and freedom that enabled his mature style to blossom. All That Heaven Allows contains all the elements of characteristically Sirkian composition: light, shade, color, and camera angles combine with his trademark use of mirrors to break up the surface of the screen. Here are all the components of the “melodramatic” style on which Sirk’s critical reputation is based and that has made him the favorite of later generations of filmmakers, from Rainer Werner Fassbinder to Quentin Tarantino, from John Waters to Pedro Almodóvar.

But at the time, Universal was just anxious to repeat its successful pairing of Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson in a romance between an older woman and an extremely handsome younger man. Wyman was still a big star but, by then, past her prime. Recently divorced from Ronald Reagan, and aware that her future lay with the soap-opera audience, she was pleased to be teamed with Hudson again. At the time, he was the new Hollywood heartthrob, who, although “out of the closet” in his personal life, had to be continually shut back in publicly and professionally by an anxious studio.

The All That Heaven Allows version of the May-September romance formula has Wyman playing Cary Scott, a well-to-do widow with two college-age children and a dull social life at the country club. The emptiness at the heart of her existence is filled when she meets Ron Kirby, the young gardener–turned–tree farmer who prunes the trees that line her all-American suburban yard—and then comes back to court her. This simple love story is disrupted by the vicious snobbery of her children and high-society acquaintances. Early in the film, Cary is at her dressing table, preparing for an evening with the Stoningham “elite.” To one side stands a vase containing the branches Ron cut for her earlier, so that Cary’s awakening interest in him carries over from the previous sequence. In a beautifully composed shot, the children first appear reflected in the mirror, coming between Cary and the vase, and then, as the camera pulls away, she is taken back into the room and toward the children. This one shot tells the story of the dilemma that Cary will face for the rest of the film and is typical of Sirk’s emblematic, economical use of cinema. His stars’ performances mesh well with this style. He gives them the screen space appropriate for their status, but the sexual charge between Cary and Ron is articulated through looks and gestures, and the roller-coaster highs and lows of their love are displaced onto the things that surround them.

Objects play their own significant part in expressing the emotions blocked by convention in small-town, middle-class 1950s America. Sirk creates a cinema in which the screen itself speaks more articulately than the protagonists, tongue-tied as they are by the codes of their fictional setting, the powers of censorship in Hollywood at the time, and the norms of the family melodrama genre. Out of these constraints, Sirk builds his film, while also using a typically melodramatic score to punctuate points and to accompany the tones and textures of the actors’ voices.

Years after their initial dismissal (and sometimes derision) by reviewers, Sirk’s successful string of big-budget soapers (and the director himself) have acquired a rich and complex critical afterlife, as different aspects and facets of the films have been reclaimed by successive phases of film criticism. For the auteurists and structuralists of the 1960s, Sirk’s mastery of cinematic language transcended the working conditions of the Hollywood studio system; feminists reclaimed him as a director of melodrama, with his women protagonists and dramas of interiority, domestic space, and sexual desire; gay critics today see a camp subtext in his films with Hudson, in which ambiguous situations can be read as double entendre.

The gap between the contemporary perception of All That Heaven Allows and that of the later critics is closed by Sirk himself, who once explained the conditions of work at the studio: “At least I was allowed to work on the material—so that I restructured to some extent some of the rather impossible scripts of the films I had to direct. Of course, I had to go by the rules, avoid experiments, stick to family fare, have ‘happy endings,’ and so on. Universal didn’t interfere with either my camera work or my cutting—which meant a lot to me.” Although All That Heaven Allows does, on the face of it, have a happy ending, its “happiness” is twisted with more than a touch of Sirkian irony. This piece originally appeared in the Criterion Collection’s 2001 DVD edition of All That Heaven Allows.

Jun 10, 2014

摘自CC官网://www.criterion.com/current/posts/96-all-that-heaven-allows-an-articulate-screen

4 ) 《深锁春光一院愁》——不要因为不重要之事改变对重要事的态度

看五六十年代的美国故事就像看宣传画一样,色彩浓郁服装华丽,妆容上更是精致到近乎苛刻,混合着尚未湮灭的贵族气息和新生力量的朝气。在奥斯卡最佳影片里,从第24届《一个美国人在巴黎》到第41届《雾都孤儿》里的众多彩色影片中,大家似乎都在尽其所能的大胆用色,在歌舞片的背景下还觉得天衣无缝新鲜有趣,放在正常故事片中便是睡前故事模样了。

在这部名字翻译的非常优美,《深锁春光一院愁》里,这种浓重色彩风格的美让影片美如油画式的走马灯。光线也是色彩搭档的好手,即便影片中园丁和富有寡妇之间的恋爱看似大胆,实际上多数时刻人们在刻意压抑、隐藏内心澎湃的情欲:当寡妇一个人在家时,客厅和走廊虽然开着灯,卧室里却是漆黑一片,这不仅反映了她内心的孤独凄冷,也侧面烘托了她与小镇多数人生活的格格不入;当她和园丁在木屋里商量着未来时,因为强烈而温暖的光线让他们留给观众的更类似是一个黑色的剪影,这时的她不再为黑暗所笼罩,不需要在黑暗中展现致命的美。

影片的故事很简单,一个富有的寡妇和她家的园丁相爱了,园丁的朋友十分欢迎优雅迷人的寡妇,而寡妇的朋友、邻居、儿女以及她生活阶层的所有人却持反对意见,二人相爱的压力与日俱增,终于在寡妇儿子离家出走、女儿在学校受人嘲笑后关系崩溃,而她,又该如何继续今后的人生呢。

对寡妇的苛刻是古往今来男权世界对女性的隐形酷刑,在否定了她们人身自由、性爱自由、思想自由后甚至还以殉葬强行保住死去男人的名声。所谓的坚贞不仅从理论上否定了女人有同等享受性爱的权利,甚至否定了女性对性爱的需求,直接将女人贬低为男性享受欢愉的工具。在这种不健康观念的压制下年老的寡妇往往沦为男性的帮凶,将她们扭曲了的女人生活的观念传输给下一代。《月亮河》里寡妇要为丈夫的死负责,并终生留在寡妇之家;中国有贞节牌坊,莫名其妙的集体狂欢把他们的意志强加给不相干的人;片中博学的女儿不赞成寡妇被迫守寡,不然就像埃及妻子必须给丈夫殉葬一样落后和无耻。与之形成对比的,是男人们对寡妇忠贞爱情的歌颂,好像寡妇的欲望和灵魂只能随着丈夫死去,活成一尊行尸样的牌坊才能保住全天下男人的颜面。奇特的是,通常这种观念越强烈的男人越管不住自己的小弟弟,他们从不相信身心合一的坚贞爱情只能属于一个人,那位喊着“存天理灭人欲”的理学家便当仁不让的传出了和儿媳乱伦的丑闻。

除却整个舆论环境对寡妇的变态围观,女性在婚姻中的角色扮演和她与儿女的关系也是令人关注的重点。为了挽回离家出走的儿子的心,以及不让正在恋爱时的女儿被人指指点点,寡妇选择了和园丁分手。她的失意、苦闷、寂寞都成了心头上的一块病,让本来健康的她患上了头痛症。朋友照样举行着派对、儿子照样不回家、女儿迅速嫁了人,寡妇撕心裂肺的痛苦并没有换来任何人的谅解和同情,相反,他们认为只有她的寂寞孤独才值得歌颂,仿佛在寡妇无欲无求的时候他们才能在自己的性生活里从容不迫的延长一分钟。

当许久不回家的儿子平安夜之后回到家中,因为买了一台母亲一直毫无兴趣的电视机而被自己的机智打动时,画面停留在了电视机里映衬出的寡妇痛苦的面庞,美丽和生气荡然无存。那是她的儿子为她建造的监狱,冠以爱的名义,这是全片最残忍的一幕。

5 ) [Film Review] All That Heaven Allows (1955) 8.4/10

An auteur maudit of his time, German émigré Douglas Sirk's renown has been considerably reappraised with much admiration for his trademark disposition of light and color, the swelling watchability sublimated from its saccharine source material, aka. the often derogated melodrama, and affecting emotional flux elicited from his sharply tricked-out players (Rock Hudson is among the staple).

Sirk's second Wyman-Hudson vehicle, ALL THAT HEAVEN ALLOWS, is a lean, Technicolor-fueled, frippery-free, love-overcoming-moral-prejudice romantic drama, a middle-class suburban widow Cary Scott (Wyman) gallantly accepts the marriage proposal from her much younger boyfriend Ron Kirby (Hudson), who is hailed from a different class bracket and has no ambition in pursuing affluence. What transpires in the wake of her decision trenchantly discloses the selfishness, snobbery, myopia and hypocrisy inherently pertaining to the objectionable mindset of small-town bourgeoisie. On paper, the story sounds platitudinous, but Sirk’s wow factor is, as always, his divine composition of the palette and setting, everything is undergone through a minutely preparatory process, from the impeccable cosmetic furnishing and elegant garbs of its dramatis personae, to its almost storybook environs, however, to counterpoise the richness on one’s eyes, Sirk is quite self-aware of not overreaching himself, ergo, the plot pans out in a reductive but expressively accurate manner, sansdevious routes, to sustain a vigorous lifeline that magically keeps a spectator rapt.

It goes without saying this approach often lives and dies with the performers, and in this case, it totally hits the bull-eye. Jane Wyman is a screen paragon who can yoke unperturbed grace with understated determination in a pinch, and step by step, Cary’s liberation from those fetters chained to a lonesome widow is limned through her pitch-perfect, layered felicity that it hits every right spot to accompany a viewer’s mirrored, visceral journey. Rock Hudson, a quintessential specimen of American masculinity and good looks, aptly elicits Ron’s larger-than-life symbol of perfection but at the same time, conveys his vulnerability and misery with pinpricks of impatience and disappointment, which injects a more personal note to the character.

As regards the peripheral roles,Gloria Talbott andWilliam Reynolds, who play Cary’s college-age children, both stoutly take it to themselves as the cardinal negative force impeding their mother’s new romance, with the former’s talk-the-talk, walk-the-walk turnabout and the latter’s sheer self-seeking callousness, god bless our offspring. But one’s heart easily goes with a solicitous Agnes Moorehead, who is always a pleasant sight as Cary’s matter-of-fact confidant and an effulgent Virginia Grey, radiating warmth even if she is not necessarily needed to do so.

Lastly, the purportedly compromised ending, stank with the inimical Catholic precept that one must suffer (both physically and mentally) plenty before finally gaining the reward, comes off as a fly in the ointment to wring a quasi-tearjerking effect, nonetheless, as vouched by Liszt’s timelessly enchanting Consolation No. 3 in the beginning, ALL THAT HEAVEN ALLOWS oozes a vintage vitality in its most luscious taste, isn’t that a delight?

referential films: Sirk’s MAGNIFICENT OBSESSION (1954, 7.1/10), WRITTEN ON THE WIND (1956, 8.0/10); Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s ALI: FEAR EATS THE SOUL (1974, 8.7/10); Todd Haynes FAR FROM HEAVEN (2002, 9.2/10).

6 ) 塞克式的幻灭与希望

新妆宜面下朱楼,深锁春光一院愁。行到中庭数花朵,蜻蜓飞上玉搔头。

刘禹锡这首闺怨词的第二小句,被用作美国电影All That Heaven Allows的译名,尽管电影中的季节不是春天(这里大约是取美好的岁月、时光之意)。“新妆宜面”本是期待爱情的状态;而锁住女主人公的,是那庭院深深,和庭院内外的傲慢与偏见。

影片的情节初看极为老套甚至浮夸。一位上流社会富有的中年寡妇Cary,一位年轻英俊、朝气蓬勃的园丁Ron,两人的爱情遭到Cary子女、朋友的一致反对。面对世俗压力,Cary放弃了这段感情。直到关键时刻,Cary才终于决定听从自己的内心回到Ron身边……

然而道格拉斯·塞克在通俗的情节背后藏着更多的表达。

塞克式美学,有一种让人心凉的幻灭感。《深锁春光一院愁》中,Cary想放弃与Ron感情的导火索,是儿子的离家出走:“如果你要嫁给他,别指望我来看望你。”看似讲道理的女儿也认为母亲不该嫁给一个一无所有的园丁。Ron对Cary说的话其实点出了问题的本质:“他们不喜欢我,是因为我不像他们的爸爸。我不是成功的商人,不是国家的栋梁。”得知Cary解除婚约后,儿子回家了,说他即将出国,给母亲买了一台电视机——一个Cary之前就跟朋友谈论过并不感兴趣的物件。当儿子兴奋地向母亲诉说这台电视有多好的时候,他没有注意到的,是映在电视机中母亲悲怆忧愁的脸庞。这个镜头让人痛心,Cary的脸被死死框在那个年代的奢侈品——电视机里,如同囿于她所处的上流社会。儿子出国,女儿嫁人,儿子甚至要考虑卖掉母亲住的房子,这时身处大宅中的Cary,体会到一种深深的孤寂。

如同塞克在下一年拍摄的作品《苦雨恋春风》中那个“一入豪门深似海”的故事,塞克的镜头里看似表现的是上流社会豪华的住宅、华美的着装、永无尽头的宴会、奢侈的生活方式,但其中无比饱满的人物情感、层次分明的色彩、恰到好处的配乐却给人一种不真实的感觉。影片中,Cary最初坚持要让Ron见她的朋友们,带他去赴宴,希望她的“朋友们”能接纳他。宴会上人们衣冠楚楚,觥筹交错;而等待她的,却是含沙射影的嘲讽与旧日曾追随她不成的男人的调戏。Ron并不会因为换上一身西装就被接纳;两人最终离开了熙熙攘攘的人群。与周围的吵闹声不匹配的,是两人深深的失望与孤独,和观众可以解读得出的隔阂。来自德国的塞克,此时营造出其同胞布莱希特提出的间离效果。如同Ron是Cary朋友圈子的局外人,我们也成为了局外人,旁观影片中纷纷攘攘人群的精神世界。

无怪乎塞克的影片被认为带有某种辛辣的讽刺性。他将一群人拍得尽可能华美,目的却不是为了赞美。《苦雨恋春风》中的Lucy,《深锁春光一院愁》中的Cary,都是贵妇人的角色,只是处在人生的不同阶段。她们的本意没有错,要对自己的家庭负责任;但是各种因素却将不应有的重负压在她们身上。Lucy的丈夫因为生育问题终日酗酒,但是她仍对其富有耐心不离不弃,直到Lucy好不容易怀孕后却又怀疑孩子不是他的,一巴掌将她打流产;Cary的儿女赞成守寡的母亲嫁人,但却必须要嫁给他们认为社会地位与其相匹配的对象,否则便粗暴地加以反对,只顾自己的面子,丝毫不顾母亲的感受。某种程度上,她们的善良被“利用”了,成为了他人自私行为的牺牲品。而两人最终的结局,都是离开了原有的家。两部影片中洛克·哈德森都扮演了“拯救者”式的角色,他来自普通家庭、做着普通的工作,他让女主角离开旧生活,和他一起开始一段全新的征程。

但是塞克的讽刺不是恶毒的,而是充满着关怀与希望。与其说他在批判上流社会的精神面貌,抑或世俗偏见对女性造成的伤害,倒不如说他在反思如何走出困境。阶级偏见、性别偏见要消除谈何容易,正因此,有人说《深锁春光一院愁》的结局过于理想化。但我以为,这正说明了塞克的乐观态度和他对人性、对爱的信任。影片中,女儿最终向母亲道歉,这是一种和解。塞克的目的,并不在说明上流社会的一切都是恶的;他描绘的,是有时表面的浮华遮蔽了人们的双眼,而事实上传统的阶级与性别偏见不应成为精神富足与幸福的障碍。

影片从金色的深秋到银白的冬季,色彩十分迷人。在我看来主人公的着装也富有暗示。Cary和Ron感情在正轨的时候,Ron穿的都是红色的衣服(准确说是红黑格子);两人面临压力处于分手边缘的时候,他的衣着颜色明显变深变暗。等到又有转机(圣诞相遇),他又穿上了红衣。另外,Cary女儿回来告诉母亲她要结婚的时候,穿的是一条红裙,与黑色着装满怀心事的憔悴母亲形成了鲜明对比,让人想起Cary影片开头阶段穿的红色礼服——那时她还没有经历这一切,尚且神采奕奕。从亮色到暗色,隐喻着因为爱情遭受的世俗偏见带给Cary的折磨。

影片结尾,Cary守护在昏迷的Ron床前。Ron醒来,说你回家了?Cary说是的,亲爱的,我回家了。落地窗外,是白色的雪与凝视他们的鹿。电视锁住了心,窗子却打开心看向外面的世界。

“我回家了”,她终于让Ron的家成为她的归宿;她说的是“回来”,这是内心、爱情、精神意义上的“回来”;这个结尾,我愿将其视作塞克的明亮希望。

(原写于2016年7月,作了一些修改与整理。)

瑟克的场面调度是对于平行蒙太奇的替代,而非如同(巴赞所提及的)奥森·威尔斯形成一种时空的完整性,反而暴露了时间的凝缩机制,成为好莱坞的一个潜在的自反时刻,甚至是《鸟人》,或迪士尼动画,高概念影片中技术处理之下的伪长镜头之雏形。另一方面,对于时间的迷恋构成了全片南方哥特基调,瑟克高饱和度的美国小镇是一个过去的精致镇纸,并随着儿子寄来的电视机——一个“新”技术物——构成了对人物精神的最后一击,作为50年代对于电影行业最大的冲击,电视在《深》中并非属于将来,而是沉浸在一种无法改变的秩序之中,维持gossip的包围——当然,也可以被理解为影像媒介本身的自反——因此吊诡的地方出现了,如果现代性无法形成某种解放,那么过时的银幕亲吻或作为道德的农场生活也不行。

瑟克使用了大量布莱希特式的疏离工具:框架镜头;歌曲插入;闪回;讽刺与戏讽;过分明显的俗套象征主义与颜色象征主义;反自然布光,等等。但这些工具并没有让观众从经常呈现情绪浓烈的主人公们的身上疏离。相反,他的电影高度情绪化,观众也严重融入角色。加之煽情音乐对于催泪效果的推波助澜,反而强化了瑟克“泪片大师”的盛名。

女人都是要别人替他决定;可是即使过了100年,我们仍要为他人而活。

瓦尔登湖、弗洛伊德,小镇中产阶级生活方式和道德(电视机)VS自由人的联合体,表现主义的色彩和用光、十分诗意,透过寡妇和年轻男子的爱情讲述了更深的主题。

男主是典型的好莱坞老式帅哥~可是男对女的爱也太突然了吧 如果你要说“这就是爱情” ok 我服了。= =。可是结尾也太drama啦 女守在昏迷的男身边,他就醒了 囧。 我若是导演,就让她在看着儿子送来的电视机时哀怨的结束~~不过这样会被观众骂死的哈哈~~【男主的真相竟然是小基友!】色彩和光线很美好~

小城之春董夫人,人言可畏苏丽珍,深锁一屋霓虹光,此身谁料是李纨,世上寂寞寡妇夜,愁煞多少电视机

好好看的melodrama! 看得我柔肠百转与千回... PS.看完之后在卫生间排队,一群奶奶在讨论Hudson好帅好帅这件事,让我想到了In Jackson Heights里面那几个老奶奶在Espresso 77一边织毛衣一边说着“我喜欢的男明星都是gay...”哈哈哈~

精准地拿捏了“寂寞”的频率,是欲语对方却挂断电话的失望与欲望,或话已说完仍情留半晌;最后沙发的黄色用得真美,非复古风格可以模仿;看的过程中,曲意地想起鲁迅的话,不惮以最坏的恶意揣测国人,他人的恶意构成的多层次地狱,是剧本最精彩之处,当然还有剧本的细腻与完整性。

stunning cinematography, fell in love with Douglas Sirk; doesn't Rock Hudson look like a greasy version of Gregory Peck

Melodrama,表现主义传统在色彩上的反映。瑟克极大影响了法斯宾德和阿尔莫多瓦,如前者酷爱的镜子框子和后者的色彩运用。剧作的社会意义在于女性独立及“传统社会”之人言可畏和子一代的对家庭瓦解(MD这就是个狗血版的小津啊)。音乐是大交响。

Everybody knows melodrama is a form of cliche, but somehow funny to make a analysis towards it.

太喜欢了。把情节剧拍成这样了还要跟韩剧和琼瑶来比,大多观众果然只看故事。

浪漫爱情片,中年寡妇与年轻男人的爱情可以反映出很多问题,核心就是过自己想过的生活,推崇《瓦尔登湖》里的自然主义,我想喜欢这本书的,其实都是非常渴望却不敢或不能脱离世俗的生活,不要听那些流言蜚语,追求自己爱情,追求自己的幸福,为自己而活。

据说从戈达尔到阿莫多瓦都喜欢Douglas Sirk的mélo,据说法斯宾德照着这部拍出了《恐惧吞噬灵魂》,可是,可是《恐惧吞噬灵魂》比这好看太多了啊……也许是年代太久远也许是上世纪美国小镇的保守程度让人无法共情也许是男主那个五十年代万人迷标准发型(男主一出场感觉仿佛看到了Cary Grant,然后发现不是,然后觉得随便吧他们打扮也实在是差不多……)让人看着很出戏,总之除了色彩鲜艳到简直可以与Dario Argento的恐怖片相比(但又没有其他美学上形式上的追求)之外,实在不知道有啥值得注意的。也许在五十年代在美国mélo也只能拍到这样了,不能用阿莫多瓦的标准要求一个上世纪好莱坞导演……

琼瑶剧式的故事,却如此细腻动人,道格拉斯塞克很懂得节奏的掌控,不同阶层的矛盾、价值观与爱情的矛盾、人物内心的纠结与转折,每一个镜头都深思熟虑。喜欢影片的色彩~

有儿有女的卡蕾爱上小她一截的园丁罗恩,横亘在他们面前的不止闲言碎语、挖苦诋毁,还有卡蕾儿女的极力反对,于是卡蕾的世界从金黄灿烂的秋步入了冰寒冷冽的冬,无私给了爱情迎头一击,中年卡蕾缺乏的,是放手去爱,管它刀山火海的豁出去。

要欣赏塞克的作品需要的智慧真是不少,[深锁春光]这部杰作身体力行地给出了拍情节剧的方法。他用声画手法把阶级这个核心动机强调出来,让妇孺皆懂;同时又用这种强化手法制造了异化感,让人觉察到背后的讽刺。这部作品于是同时向外发出两个波段,灵敏的接收者应能捕捉到这种多声部造就的立体感。

林肯中心把这部和《恐惧吞噬灵魂》《远离天堂》三部连放简直太厉害了,一脉相承的鲜艳色彩和细腻的女性心理刻画。很多那个时代的符号,比如电视机,就像一道枷锁;女主的女儿虽然上了大学,却仍旧是传统女性的思维。瑟克片里的纽约郊区小镇,简直全是恶意和无趣啊,当然,还好我们还有园丁

结尾男主失忆认不出女主就神作了 这片子很好地印证了Klinger的批评 所谓的反抗型好莱坞也不过是主流好莱坞话语的变体 女主对自己城市中产的突破并不突破中产阶级底线 而只是建立一种新的中产生活--乡村中产 这种突破对于保守的观众是非常具有吸引力的但其真正匮乏的正是对主流的反抗

男主掉雪堆里一幕笑死我了,这老电影的演员吧 ,表演的痕迹咋都那么重呢,,表情什么的都太好玩了,这男主真是一看就不是个好东西的脸啊,看到他就想到菊花+aids