详细剧情

长篇影评

1 ) 我看到了淡淡的一缕忧伤,进而感叹浮生若梦

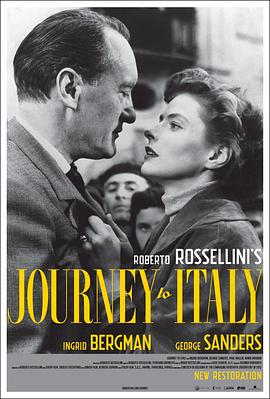

1948年,《卡萨布兰卡》女主角英格丽·褒曼被名导罗西里尼的战争三部曲之一《罗马,不设防的城市》深深感动,并写给他一封信表示期望能与之合作,罗西里尼也为之动容。两年之后,两人在合作拍摄《火山边缘之恋》时坠入情网,褒曼给罗西里尼产下一子,褒曼清纯贤惠形象被毁,舆论哗然。不久,褒曼与丈夫离婚,并与罗西里尼结婚。此后一段时期就被称为罗西里尼的“英格丽·褒曼时代”。但是两人的事业并未因此更进一步,相反地,他们遭到了以好莱坞为首的电影界的抵制,两人后来合作的电影大都在业内颇有口碑却难以与观众见面。整体来看,这段时期的作品反响远不如其他时期作品。 本片就是这个时期的作品,2013年《视与听》杂志邀请846位影评人共同参与投票,每人选出个人心中的影史十佳。票数汇总之后,得出影史佳片的50强。本片荣登Top50 #41,该片也曾入选《电影手册》年度十佳。 本片故事内容是战后一对中产阶级夫妻的在意大利的一次旅行,通过彼此感情的碰撞展示了战后欧洲民众的生态。故事的男主人公喜欢沾花惹草,女主人公喜欢感怀伤逝。在这次旅途中,男女主人公因为情感不和,中途各奔东西。但是经历这段不美好的意大利之旅,随着时间的推移,俩人逐渐认识到时光易逝,生命短暂,而爱情也并非永恒,需要彼此妥协,彼此维护。通过这对男女的感情变故,罗西里尼向我们展示了战后欧洲普通人的精神面貌,隐约显露出一股淡淡的忧伤。 通观全片,不能绝对地说这个故事的情感重点是婚姻感情,我觉得罗西里尼似乎有意识地情感重点停靠在“战争”这个点上。整部电影自始至终,镜头里都充斥着战后人们消极、迷茫、颓废的生活态度。罗西里尼通过这对男女的情感变故来展现欧洲战后普通人的情感变化,从他们游历途中的所见,以及自身的情感波动,反映出整个欧洲的思想意识形态。导演没有采用形式主义手法,刻意夸大人们的情感变动,而是把这种变动隐含在“婚姻变故”中。从这对恋人的爱情横生出来的枝节,看出欧洲二战之后的一种精神面貌。 男主角代表了这样一类人。客观地看待现状,并不想主动倾注自己的精力去改变现状。男主角面对婚变的做法是“逃避”,因为跟女主角的一些意见不合,男主角在某天清晨突然消失的无影无踪。他之所以寻欢作乐,不过是为了逃避目前的现状,而不是真的想要跑去玩乐。这一点,在男主人面对妓女的时候表现的极为明显。表面上,他在调情,但实质上,他也牵挂着女主角。这类人经历了战争,遭受了战争的创伤,他们却并不想着去改变什么,而是选择逃避,即便他们再怎么关爱着欧洲的现状。 而影片中,女主角在面对婚变时,她努力表现得若无其事,她明知道自己过得不够快乐,却努力装得美好非常。我们关心的并不是男主人的“游览”,而是女主角的“游览”,她的所见给我们展示了欧洲战后的现状。自然景观冷清,带着颓废,某处安放的一排排尸骨,静谧,哀伤。当镜头从女主角角度看去的时候,我们才真正感受到那股淡淡的忧伤。它不仅仅关乎男女主角之间破裂的爱情,更关乎整个欧洲的情感裂痕。 面对陈列的尸骨和被挖掘出来的死尸时,女主角几欲泪流。她因而想到了时光短暂,爱情未能永远,看到了爱情最终败给了生命,看到了她所不能接受的一切。 一个民族不经历战争,就不会懂得战争之痛。一个人不见识死亡,就揣摩不到生命的厚度,就不知道现在拥有的究竟何等珍贵。 《卧虎藏龙》里有句台词,我们能够触摸的,都没有永远。一切能够现在把握的,都看不到永久。能在一起的时候,请别轻易分离。 又突然想到李白一首诗。“夫天地者,万物之逆旅;光阴者,百代之过客。而浮生若梦,为欢几何?”想到此处,反观本片,这股淡淡的忧伤便越发明显。

2 ) 名大于实

3 ) 罗西里尼眼中的社会和生活

做为打酱油的非专业人士,纯粹是冲着罗西里尼的名气看的。如果当作一个爱情风光片,那槽点确实很多,但想到罗西里尼是意大利新现实主义的代表人物,就必须从时代的角度去体会他想表达的主题。

他选择在维苏威火山爆发中被毁灭的庞贝古城作为片中风景素材,应该映射结束不久的二战给世界带来的灾难,而那些希腊神话主题雕塑、古要塞引发的是对历史的思考,正义与邪恶,善与美,生命和死亡,这些永恒的主题一直在轮回。片中很多那不勒斯的市井风情和节日场面,又不断将观众带回到现实生活,同时,这一切元素全部融在明媚的阳光和美丽的海景中,伴随着悠扬的拿波里民歌,时空就这样交织在一起。

男女主人公的婚姻并不只是一对夫妻的爱情命运,而寓意着每一个人的命运,在一次世界毁灭之后,生活总会开始,但生活会走向哪里?这不正是战后整个世界的思考吗?当二人看到庞贝新发掘出来的一对夫妇的石膏尸体模型,妻子悲伤之情不能自已,在灾难面前,一切都是那么脆弱和无力,而又有多少相爱的人能一起死去?那死在一起的夫妇是真正相爱吗?

片尾,当夫妇被节日的游行队伍冲散,最后拼命寻找对方,相聚之后的那一段话应该是罗西里尼想表达的主题思想:我们本来相爱,却总是彼此折磨,可能是我们太容易被伤害了!

此外,片中那不勒斯风光和民俗风情的场景很值得细细品味,对了解意大利南部的传统文化有帮助。例如浓重的宗教色彩,看到圣像后满街人狂热的追随和跪拜;男主人向别墅里的意大利胖女仆要水的一段令人捧腹的对话,典型的朴实、泼辣、传统保守的南部大妈形象。这类有意思的细节在片中很多。

4 ) 从庞贝挖掘出来的尸体说起

亚历山大刚和妻子坦白离婚的事,夫妇被热情地邀请去看尸骨挖掘,这一段处理得非常棒,把拥抱在一起的夫妇尸体与亚历山大夫妇的情感状态建立了某种神秘的联系。生命太过脆弱了,爱情也败给了它,谁又能知道那对拥抱着死去的夫妇是真心相爱呢?兴许也是在不断的妥协与退让中,只是死亡成就了它们的爱情,将其永恒化了。那么,影片最后亚历山大夫妇在神面前的相拥和解就一定是因为爱吗?不过是害怕再度迷失,害怕再度虚空,不过是无处取暖时祈求对方的一点温度罢了,毕竟这里到处弥漫着死亡,需要新生命(孩子)来弥补破裂的情感。因此,透过女主角的眼睛,我们可以看到战后的街上,婴儿和孕妇都增加了。可以说,整个民族的情感创伤都企图通过婴孩来弥合。

5 ) Letter on Rossellini

Letter on Rossellini Jacques Rivette Translated by Tom Milne.

'Ordinance protects. Order reigns.'

You don't think much of Rossellini; you don't, so you tell me, like Voyage to Italy; and everything seems to be in order. But no; you are not assured enough in your rejection not to sound out the opinion of Rossellinians. They provoke you, worry you, as if you weren't quite easy in your mind about your taste. What a curious attitude!

But enough of this bantering tone. Yes, I have a very special admiration for Rossellini's latest film (or rather, the latest to be released here). On what grounds? Ah, that's where it gets more difficult. I cannot invoke exaltation, emotion, joy: these are terms you will scarcely admit as evidence; but at least you will, I trust, understand them. (If not, may God help you.)

To gratify you, let us change the tone yet again. Mastery, freedom, these are words you can accept; for what we have here is the film in which Rossellini affirms his mastery most clearly, and, as in all art, through the free exercise of his talents; I shall come back to this later. First I have something to say which should be of greater concern to you: if there is a modern cinema, this is it. But you still require evidence.

- If I consider Rossellini to be the most modern of film-makers, it is not without reason; nor is it through reason, either. It seems to me impossible to see Voyage to Italy without receiving direct evidence of the fact that the film opens a breach, and that all cinema, on pain of death, must pass through it. (Yes, that there is now no other hope of salvation for our miserable French cinema but a healthy transfusion of this young blood.) This is, of course, only a personal impression. And I should like forthwith to forestall a misunderstanding: for there are other films, other film-makers doubtless no less great than this; though less, how shall I put it, exemplary. I mean that having reached this point in their careers, their creation seems to close in on itself, what they do is of importance for, and within the perspectives of, this creation. Here, undoubtedly, is the culmination of art, no longer answerable to anyone but itself and, once the experimental fumblings and explorations are past, discouraging disciples by isolating the masters: their domain dies with them, along with the laws and the methods current there. Renoir, Hawks, Lang belong here, of course, and in a certain sense, Hitchcock. Le Carrosse d'Or may inspire muddled copies, but never a school; only presumption and ignorance make these copies possible, and the real secrets are so well hidden within the series of Chinese boxes that to unravel them would probably take as many years as Renoir's career now stretches to; they merge with the various mutations and developments undergone over thirty years by an exceptionally keen and exacting creative intelligence. In its energy and dash, the work of youth or early maturity remains a reflection of the movements of everyday life; animated by a different current, it is shackled to time and can detach itself only with difficulty. But the secret of Le Carrosse d'Or is that of creation and the problems, the trials, the gambles it subjects itself to in order to perfect an object and give it the autonomy and the subtlety of an as yet unexplored world. What example is there here, unless that of discreet, patient work which finally effaces all traces of its passage? But what could painters or musicians ever retain from the later works of Poussin or Picasso, Mozart or Stravinsky -- except a salutary despair. There is reason to think that in a decade or so Rossellini too will attain (and acclimatise himself to) this degree of purity; he has not reached it yet -- luckily, it may be said; there is still time to follow him before within him in his turn eternity . . . (1); while the man of action still lives in the artist.

- Modern, I said; after a few minutes watching Voyage to Italy, for instance, a name kept recurring in my mind which seems out of place here: Matisse. Each image, each movement, confirmed for me the secret affinity between the painter and the film-maker. This is simpler to state than to demonstrate; I mean to try, however, though I fear that my main reasons may seem rather frivolous to you, and the rest either obscure or specious. All you need do, to start with, is look: note, throughout the first part, the predilection for large white surfaces, judiciously set off by a neat trait, an almost decorative detail; if the house is new and absolutely modem in appearance, this is of course because Rossellini is particularly attracted to contemporary things, to the most recent forms of our environment and customs; and also because it delights him visually. This may seem surprising on the part of a realist (and even neo-realist); for heaven's sake, why? Matisse, in my book, is a realist too: the harmonious arrangement of fluid matter, the attraction of the white page pregnant with a single sign, of virgin sands awaiting the invention of the precise trait, all this suggests to me a more genuine realism than the overstatements, the affectations, the pseudo-Russian conventionalism of Miracle in Milan; all this, far from muffling the film-maker's voice, gives him a new, contemporary tone that speaks to us through our freshest, most vital sensibility; all this affects the modem man in us, and in fact bears witness to the period as faithfully as the narrative does; all this in fact deals with the honnete homme of 1953 or 1954; this, in fact, is the theme.

- On the canvas, a spontaneous curve circumscribes, without ever pinning down, the most brilliant of colors; a broken line, nevertheless unique, encompasses matter that is miraculously alive, as though transferred intact from its source. On the screen, a long parabola, pliant and precise, guides and controls each sequence, then punctually closes again. Think of any Rossellini film: each scene, each episode will recur in your memory not as a succession of shots and compositions, a more or less harmonious succession of more or less brilliant images, but as a vast melodic phrase, a continuous arabesque, a single implacable line which leads people ineluctably towards the as yet unknown, embracing in its trajectory a palpitant and definitive universe; whether it be a fragment from Paisa, a fioretto from The Flowers of St Francis, a 'station' in Europa '51, or these films in their entirety, the symphony in three movements of Germany, Year Zero, the doggedly ascending scale of The Miracle or Stromboli (musical metaphors come as spontaneously as visual ones) -- the indefatigable eye of the camera invariably assumes the role of the pencil, a temporal sketch is perpetuated before our eyes (but rest assured, without attempts to instruct us by using slow motion to analyze the Master's inspiration for our benefit) (2); we live through its progress until the final shading off, until it loses itself in the continuance of time just as it had loomed out of the whiteness of the canvas. For there are films which begin and end, which have a beginning and an ending, which conduct a story through from its initial premise until everything has been restored to peace and order, and there have been deaths, a marriage or a revelation; there is Hawks, Hitchcock, Murnau, Ray, Griffith. And there are the films quite unlike this, which recede into time like rivers to the sea; and which offer us only the most banal of closing images: rivers flowing, crowds, armies, shadows passing, curtains falling in perpetuity, a girl dancing till the end of time; there is Renoir and Rossellini. It is then up to us, in silence, to prolong this movement that has returned to secrecy, this hidden arc that has buried itself beneath the earth again; we have not finished with it yet. (Of course all this is arbitrary, and you are right: the first group prolong themselves too, but not quite in the same way, it seems to me; they gratify the mind, their eddies buoy us up, whereas the others burden us, weigh us down. That is what I meant to say.) And there are the films that rejoin time through a painfully maintained immobility; that expend themselves without flinching in a perilous position on summits that seem uninhabitable; such as The Miracle, Europa '51.

- Is it toon soon for such enthusiasms? A little too soon, I fear; so let us return to earth and, since you wish it, talk of compositions: but this lack of balance, this divergence from the customary centres of gravity, this apparent uncertainty which secretly shocks you so deeply, forgive me if once again I see the head of Matisse here, his asymmetrism, the magisterial 'falseness' in composition, tranquilly eccentric, which also shocks at first glance and only subsequently reveals its secret equilibrium where values are as important as the lines, and which gives to each canvas this unobtrusive movement, just as here it yields at each moment this controlled dynamism, this profound inclination of all elements, all arcs and volumes at that instant, towards the new equilibrium, and in the following second of the new disequilibrium towards the next; and this might be learnedly described as the art of succession in composition (or rather, of successive composition) which, unlike all the static experiments that have been stifling the cinema for thirty years, seems to me to stand to reason as the only visual device legitimate for the film-maker.

- I shall not labor the point further: any comparison soon becomes irksome, and I fear that this one has already continued too long; in any case, who will be convinced except those who see the point as soon as it is stated? But allow me just one last remark -- concerning the Trait: grace and gaucheness indissolubly linked. Render tribute in either case to a youthful grace, impetuous and stiff, clumsy and yet disconcertingly at ease, that seems to me to be in the very nature of adolescence, the awkward age, where the most overwhelming, the most effective gestures seem to burst unexpectedly in this way from a body strained by an acute sense of embarrassment. Matisse and Rossellini affirm the freedom of the artist, but do not misunderstand me: a controlled, constructed freedom, where the initial building finally disappears beneath the sketch. For this trait must be added which will resume all the rest: the common sense of the draft. A sketch more accurate, more detailed than any detail and the most scrupulous design, a disposition of forces more accurate than composition, these are the sort of miracles from which springs the sovereign truth of the imagination, of the governing idea which only has to put in an appearance to assume control, summarily outlined in broad essential strokes, clumsy and hurried yet epitomizing twenty fully rounded studies. For there is no doubt that these hurried films, improvised out of very slender means and filmed in a turmoil that is often apparent from the images, contain the only real portrait of our times; and these times are a draft too. How could one fail suddenly to recognize, quintessentially sketched, ill-composed, incomplete, the semblance of our daily existence? These arbitrary groups, these absolutely theoretical collections of people eaten away by lassitude and boredom, exactly as we know them to be, as the irrefutable, accusing image of our heteroclite, dissident, discordant societies. Europa '51, Germany, Year Zero, and this film which might be called Italy '53, just as Paisa was Italy '44, these are our mirror, scarcely flattering to us; let us yet hope that these times, true in their turn like these kindred films, will secretly orient themselves towards an inner order, towards a truth which will give them meaning and in the end justify so much disorder and flurried confusion.

- Ah, now there is cause for misgivings: the author is showing the cloven hoof. I can hear the mutters already: coterie talk, fanaticism, intolerance. But this famous freedom, and much vaunted freedom of expression, but more particularly the freedom to express everything of oneself, who carries it further? -- To the point of immodesty, comes the answering cry; for the strange thing is that people still complain, and precisely those people who are loudest in their claims for freedom (to what end? the liberation of man? I'll buy that, but from what chains? That man is free is what we are taught in the catechism, and what Rossellini quite simply shows; and his cynicism is the cynicism of great art). 'Voyage to Italy is the Essays of Montaigne,' our friend M prettily says; this, it seems, is not a compliment; permit me to think otherwise, and to wonder at the fact that our era, which can no longer be shocked by anything, should pretend to be scandalized because a film-maker dares to talk about himself without restraint; it is true that Rossellini's films have more and more obviously become amateur films; home movies; Joan of Arc at the Stake is not a cinematic transposition of the celebrated oratorio, but simply a souvenir film of his wife's performance in it just as The Human Voice was primarily the record of a performance by Anna Magnani (the most curious thing is that Joan of Arc at the Stake, like The Human Voice, is a real film, not in the least theatrical in its appeal; but this would lead us into deep waters). Similarly, Rossellini's episode in We the Women is simply the account of a day in Ingrid Bergman's life; while Voyage to Italy presents a transparent fable, and George Sanders a face barely masking that of the film-maker himself (a trifle tarnished, no doubt, but that is humility), -- Now he is no longer filming just his ideas, as in Stromboli or Europa '51, but the most everyday details of his life; this life, however, is 'exemplary' in the fullest sense that Goethe implied: that everything in it is instructive, including the errors; and the account of a busy afternoon in Mrs. Rossellini's life is no more frivolous in this context than the long description Eckermann gives us of that beautiful day, on May 1st 1825, when he and Goethe practiced archery together. -- So there, then, you have this country, this city; but a privileged country, an exceptional city, retaining intact innocence and faith, living squarely in the eternal; a providential city; and here, by the same token, is Rossellini's secret, which is to move with unremitting freedom, and one single, simple motion, through manifest eternity: the world of the incarnation; but that Rossellini's genius is possible only within Christianity is a point I shall not labor, since Maurice Scherer' has already argued it better than I could ever hope to do, in a magazine: Les Cahiers du Cinema, if I remember right. (3)

- Such freedom, absolute, inordinate, whose extreme license never involves the sacrifice of inner rigor, is freedom won; or better yet, earned. This notion of earning is quite new, I fear, and astonishing even though evident; so the next thing is, earned how? -- By virtue of meditation, of exploring an idea or an inner harmony; by virtue of sowing this predestined seed in the concrete world which is also the intellectual world ('which is the same as the spiritual world'); by virtue of persistence, which then justifies any surrender to the hazards of creation, and even urges our hapless creator to such surrender; once again the idea becomes flesh, the work of art, the truth to come, becomes the very life of the artist, who can thereafter no longer do anything that steers clear of this pole, this magnetic point. -- And thereafter we too, I fear, can barely leave this inner circle any more, this basic refrain that is reprised chorally: that the body is the soul, the other is myself, the object is the truth and the message; and now we are also trapped by this place where the passage from one shot to the next is perpetual and infinitely reciprocal; where Matisse's arabesques are not just invisibly linked to their hearth, do not merely represent it, but are the fire itself.

- This position offers strange rewards; but grant me another detour, which like all detours will have the advantage of getting us more quickly to where I want to take you. (It is becoming obvious anyway that I am not trying to follow a coherent line of argument, but rather that I am bent on repeating the same thing in different ways; affirming it on different keyboards.) I have already spoken of Rossellini's eye, his look; I think I even made a rather hasty comparison with Matisse's tenacious pencil; it doesn't matter, one cannot stress the film-maker's eye too highly (and who can doubt that this is where his genius primarily lies?), and above all its singularity. Ah, I'm not really talking about Kino-Eye, about documentary objectivity and all that jazz; I'd like to have you feel (with your finger) more tangibly the powers of this look: which may not be the most subtle, which is Renoir, or the most acute, which is Hitchcock, but is the most active; and the point is not that it is concerned with some transfiguration of appearances, like Welles, or their condensation, like Murnau, but with their capture: a hunt for each and every moment, at each perilous moment a corporeal quest (and therefore a spiritual one; a quest for the spirit by the body), an incessant movement of seizure and pursuit which bestows on the images some indefinable quality at once of triumph and agitation: the very note, indeed, of conquest. -- (But perceive, I beg you, wherein the difference lies here; this is not some pagan conquest, the exploits of some infidel general; do you perceive the fraternal quality in this word, and what sort of conquest is implied, what it comprises of humility, of charity?)

- For 'I have made a discovery': there is a television aesthetic; don't laugh, that isn't my discovery, of course; and what this aesthetic is (what it is beginning to be) I learned just recently from an article by Andre Bazin (4) which, like me, you read in the colored issue of Cahiers du Cinema (definitely an excellent magazine). But this is what I realized: that Rossellini's films, though film, are also subject to this direct aesthetic, with all it comprises of gamble, tension, chance and providence (which in fact chiefly explains the mystery of Joan of Arc at the Stake, where each shot change seems to take the same risks, and induce the same anxiety, as each camera change). So there we are, because of a film this time, ensconced in the darkness, holding our breath, eyes riveted to the screen which is at last granting us such privileges: spying on our neighbor with the most appalling indiscretion, violating with impunity the physical intimacy of people who are quite unaware of being exposed to our fascinated gaze; and in consequence, to the imminent rape of their souls. But in just punishment, we must instantly suffer the anguish of anticipating, of prejudging what must come after; what weight time suddenly lends to each gesture; one does not know what is going to happen, when, how; one has a presentiment of the event, but without seeing it take shape; everything here is fortuitous, instantly inevitable; even the sense of hereafter, within the impassive web of duration. So, you say, the films of a voyeur? -- or a seer.

- Here we have a dangerous word, which has been made to mean a good many silly things, and which I don't much like using; again you're going to need a definition. But what else can one call this faculty of seeing through beings and things to the soul or the ideal they carry within them, this privilege of reaching through appearances to the doubles which engender them? (Is Rossellini a Platonist? -- Why not, after all he was thinking of filming Socrates.) Because as the screening went on, after an hour went by I wasn't thinking of Matisse any more, I'm afraid, but of Goethe: the art of associating the idea with the substance first of all in the mind, of blending it with its object by virtue of meditation; but he who speaks aloud of the object, through it instantly names the idea. Several conditions are necessary, of course: and not just this vital concentration, this intimate mortification of reality, which are the artist's secret and to which we have no access; and which are none of our business anyway. There is also the precision in the presentation of this object, secretly impregnated; the lucidity and the candor (Goethe's celebrated 'objective description'). This is not yet enough; this is where ordering comes into play, no, order itself, the heart of creation, the creator's design; what is modestly known in professional terms as the construction (and which has nothing to do with the assembling of shots currently in vogue; it obeys different laws); that order, in other words, which, giving precedence to each appearance according to merit, within the illusion that they are simply succeeding one another, forces the mind to conceive another law than chance for their judicious advent. This is something narrative has known, in film or novel, since it grew up. Novelists and film-makers of long standing, Stendhal and Renoir, Hawks and Balzac, know how to make construction the secret element in their work. Yet the cinema turned its back on the essay (I employ A. M. 's (5) word), and repudiated its unfortunate guerrillas, Intolerance, La Regle du Jeu, Citizen Kane. There was The River, the first didactic poem: now there is Voyage to Italy which, with absolute lucidity, at last offers the cinema, hitherto condemned to narrative, the possibility of the essay.

- For over fifty years now the essay has been the very language of modern art; it is freedom, concern, exploration, spontaneity; it has gradually -- Gide, Proust, Valery, Chardonne, Audiberti -- buried the novel beneath it; since Manet and Degas it has reigned over painting, and gives it its impassioned manner, the sense of pursuit and proximity. -- But do you remember that rather appealing group some years ago which had chosen some number or other as their objective and never stopped clamouring for the 'liberation' of the cinema; (6)don't worry, for once it had nothing to do with the advancement of man; they simply wanted the Seventh Art to enjoy a little of that more rarefied air in which its elders were flourishing; a very proper feeling lay behind it all. It appears, however, that some of the survivors don't care at all for Voyage to Italy; this seems incredible. For here is a film that comprises almost everything they prayed for: metaphysical essay, confession, log-book, intimate journal -- and they failed to realize it. This is an edifying story, and I wanted to tell you the whole of it.

- I can see only one reason for this; I fear I may be being malicious (but maliciousness, it seems, is to today's taste): this is the unhealthy fear of genius that holds sway this season. The fashion is for subtleties, refinements, the sport of smart-set kings; Rossellini is not subtle but fantastically simple. Literature is still the arbiter: anyone who can do a pastiche of Moravia has genius; ecstasies are aroused by the daubings of a Soldati, Wheeler, Fellini (we'll talk about Mr. Zavattini another time); tiresome repetitions and longueurs are set down as novelistic density or the sense of time passing; dullness and drabness are the effect of psychological subtlety. -- Rossellini falls into this swamp like a butterfly broken on the wheel; reproving eyes are turned away from this importunate yokel. (7) And in fact nothing could be less literary or novelistic; Rossellini does not care much for narration, and still less for demonstration; what business has he with the perfidies of argumentation? Dialectic is a whore who sleeps with all odds and ends of thought, and offers herself to any sophism; and dialecticians are riff-raff. -- His heroes prove nothing, they act; for Francis of Assisi, saintliness is not a beautiful thought. If it so happens that Rossellini wants to defend an idea, he too has no other way to convince us than to act, to create, to film; the thesis of Europa '51, absurd as each new episode starts, overwhelms us five minutes later, and each sequence is above alt the mystery of the incarnation of this idea; we resist the thematic development of the plot, but we capitulate before Bergman's tears, before the evidence of her acts and of her suffering; in each scene the film-maker fulfils the theorist by multiplying him to the highest unknown quantity. But this time there is no longer the slightest impediment: Rossellini does not demonstrate, he shows. And we have seen: that everything in Italy has meaning, that all of Italy is instructive and is part of a profound dogmatism, that there one suddenly finds oneself in the domain of the spirit and the soul; all this may perhaps not belong to the kingdom of pure truths, but is certainly shown by the film to be of the kingdom of perceptible truths, which are even more true. There is no longer any question of symbols here, and we are already on the road towards the great Christian allegory. Everything now seen by this distraught woman, lost in the kingdom of grace, these statues, these lovers, these pregnant women who form for her an omnipresent, haunting cortege, and then those huddled corpses, those skulls, and finally those banners, that procession for some almost barbaric cult, everything now radiates a different light, everything reveals itself as something else; here, visible to our eyes, are beauty, love, maternity, death, God.

- All rather outmoded notions; yet there they are, visible; all you can do is cover your eyes or kneel. There is a moment in Mozart where the music suddenly seems to draw inspiration only from itself, from an obsession with a pure chord, all the rest being but approaches, successive explorations, and withdrawals from this supreme position where time is abolished. All art may perhaps reach fruition only through the transitory destruction of its means, and the cinema is never more great than in certain moments that transcend and abruptly suspend the drama: I am thinking of Lillian Gish feverishly spinning round, of Jannings' extraordinary passivity, the marvelous moments of tranquility in The River, the night sequence in Tabu with its slumbers and awakenings; of all those shots which the very greatest film-makers can contrive at the heart of a Western, a thriller, a comedy, where the genre is suddenly abolished as the hero briefly takes stock of himself (and above all of those two confessions by Bergman and Anne Baxter, those two long self-flashbacks by heroines who are the exact center and the kernel of Under Capricorn and I Confess). What am I getting at? This: nothing in Rossellini better betokens the great film-maker than those vast chords formed within his films by all the shots of eyes looking; whether those of the small boy turned on the ruins of Berlin, or Magnani's on the mountain in The Miracle, or Bergman's on the Roman suburbs, the island of Stromboli, and finally all of Italy; (and each time the two shots, one of the woman looking, then her vision; and sometimes the two merged); a high note is suddenly attained which thereafter need only be held by means of tiny modulations and constant returns to the dominant (do you know Stravinsky's 1952 Cantata?); similarly the successive stanzas of The Flowers of St Francis are woven together on the ground bass (readable at sight) of charity. -- Or at the heart of the film is this moment when the characters have touched bottom and are trying to find themselves without evident success; this vertiginous awareness of self that grips them, like the fundamental note's own delighted return to itself at the heart of a symphony. Whence comes the greatness of Rome, Open City, of Paisa, if not from this sudden repose in human beings, from these tranquil essays in confronting the impossible fraternity, from this sudden lassitude which for a second paralyses them in the very course of the action? Bergman's solitude is at the heart of both Stromboli and Europa '51: vainly she veers, without apparent progress; yet without knowing it she is advancing, through the attrition of boredom and of time, which cannot resist so protracted an effort, such a persistent concern with her moral decline, a lassitude so unweary, so active and so impatient, which in the end will undoubtedly surmount this wall of inertia and despair, this exile from the true kingdom.

- Rossellini's work 'isn't much fun'; it is deeply serious, even, and turns its back on comedy; and I imagine that Rossellini would condemn laughter with the same Catholic virulence as Baudelaire; (and Catholicism isn't much fun either, despite its worthy apostles. -- Dov'e la liberta? should make very curious viewing from this point of view). What is it he never tires of saying? That human beings are alone, and their solitude irreducible; that, except by miracle or saintliness, our ignorance of others is complete; that only a life in God, in his love and his sacraments, only the communion of the saints can enable us to meet, to know, to possess another being than ourselves alone; and that one can only know and possess oneself in God. Through all these films human destinies trace separate curves, which intersect only by accident; face to face, men and women remain wrapped in themselves, pursuing their obsessive monologues; delineation of the 'concentration camp world' (8) of men without God. Rossellini, however, is not merely Christian, but Catholic; in other words, carnal to the point of scandal; one recalls the outrage over The Miracle; but Catholicism is by vocation a scandalous religion; the fact that our body, like Christ's, also plays its part in the divine mystery is something hardly to everyone's taste, and in this creed which makes the presence of the flesh one of its dogmas, there is a concrete meaning, weighty, almost sensual, to flesh and matter that is highly repugnant to chaste spirits: their 'intellectual evolution' no longer permits them to participate in mysteries as gross as this. In any case, Protestantism is more in fashion, especially among skeptics and free-thinkers; here is a more intellectual religion, a shade abstract, that instantly places the man for you: Huguenot ancestry infallibly hints at a coat of arms. -- I am not likely to forget the disgusted expressions with which, not so long ago, some spoke of Bergman's weeping and snivelling in Stromboli. And it must be admitted that this goes (Rossellini often does) to the limits of what is bearable, of what is decently admissible, to the very brink of indelicacy. The direction of Bergman here is totally conjugal, and based on an intimate knowledge less of the actress than of the woman; we may also add that our little world of cinema finds it difficult -- when the couple are not man and wife (9) -- to accept a notion of love like this, with nothing joyous or extravagant about it, a conception so serious and genuinely carnal (let us not hesitate to repeat the word) of a sentiment more usually disputed nowadays by either eroticism or angelism; but leave it to the Dolmances (10) among us to take offence at the way it is presented (or even just its reflection, like a watermark, on the face of the submissive wife), as though at some obscenity quite foreign to their light, amusing -- and so very modern -- fancies.

- Enough of that; but do you now understand what this freedom is: the freedom of the ardent soul, cradled by providence and grace which, never abandoning it to its tribulations, save it from perils and errors and make each trial redound to its glory. Rossellini has the eye of a modern, but also the spirit; he is more modern than any of us; and Catholicism is still as modern as anything. You are weary of reading me; I am beginning to tire of writing to you, or at least my hand is; I would have liked to tell you many more things. One will suffice: the striking novelty of the acting, which here seems to be abolished, gradually killed off by a higher necessity; all flourishes, all glowing enthusiasms, all outbursts must yield to this intimate pressure which forces them to efface themselves and pass on with the same humble haste, as though in a hurry to finish and be done with it. This way of draining actors must often infuriate them, but there are times when they should be listened to, others when they should be silenced. If you want my opinion, I think that this is what acting in the cinema tomorrow will be like. Yet how we have loved the American comedies, and so many little films whose charm lay almost entirely in the bubbling inventiveness of their movements and attitudes, the spontaneous felicities of some actor, the pretty poutings and fluttering eyelashes of a smart and saucy actress; that one of the cinema's aims should be this delightful pursuit of movement and gesture was true yesterday, and even true two minutes ago, but after this film may not be so any longer; the absence of studied effects here is superior to any successful pursuit, the resignation more beautiful than any glow of enthusiasm, the inspired simplicity loftier than the most dazzling performance by any diva. This lassitude of demeanor, this habit so deeply ingrained in every movement that the body no longer vaunts them, but rather restrains them, keeps them within itself, this is the only kind of acting we shall be able to take for a long time to come; after this taste of pungency, all sweetness is but insipid and unremembered.

- With the appearance of Voyage to Italy, all films have suddenly aged ten years; nothing is more pitiless than youth, than this unequivocal intrusion by the modem cinema, in which we can at last recognize what we were vaguely awaiting. With all due deference to recalcitrant spirits, it is this that shocks or troubles them, that vindicates itself today, it is in this that truth lies in 1955. Here is our cinema, those of us who in our turn are preparing to make films (did I tell you, it may be soon); as a start I have already suggested something that intrigues you: is there to be a Rossellini school? and what will its dogmas be? -- I don't know if there is a school, but I do know there should be: first, to come to an understanding about the meaning of the word realism, which is not some rather simple scriptwriting technique, nor yet a style of mise en scene, but a state of mind: that a straight line is the shortest distance between two points; (judge your De Sicas, Lattuadas and Viscontis by this yardstick). Second point: a fig for the skeptics, the rational, the judicious; irony and sarcasm have had their day; now it is time to love the cinema so much that one has little taste left for what presently passes by that name, and wants to impose a more exacting image of it. As you see, this hardly comprises a program, but it may be enough to give you the heart to begin. This has been a very long letter. But the lonely should be forgiven: what they write is like the love letter that goes astray. To my mind, anyway, there is no more urgent topic today. One word more: I began with a quotation from Peguy; here is another in conclusion: 'Kantism has unsullied hands'(shake hands, Kant and Luther, and you too, Jansen), 'but it has no hands'.

Yours faithfully,

Jacques Rivette

NOTES:

- A reference to the first line of Mallarme's poem, Le Tombeau d'Edgar Poe: 'Tel qu'en Lui-meme enfin l'etemite le change'. (Trans.)

- A reference to Clouzot's Le Mystere Picasso. (Trans.)

- 'Genie du Christianisme' by Maurice Scherer (Eric Rohmer) in Cahiers du Cinema No. 25. July 1953.

- 'Pour contribuer a une erotologie de la Television' in Cahiers du Cinema, No, 42.

- Probably Andre Martin. (Trans.)

- Possibly a reference to Ricciotto Canudo (1879-1923) and his Club des Amis du Septieme Art. (Trans.)

- Rivette's original of this sentence reads: 'Rossellini tombe dans ce marecage comme le pave de ('ours; on se detourne avec des moues reprobatrices de ce paysan du Danube.' The bear and the Danube peasant are references to Fables by La Fontaine. (Trans.)

- Rivette was referring to David Roussel's book, L'Univers Concenrationnaire. (Trans.)

- The adulterous affair between Rossellini and Bergman. which began during the shooting of Stromboli (1949); and their subsequent child, caused an enormous press scandal which virtually exiled Bergman from Hollywood. (Ed.)

- A character in De Sade's La Philosophie dans le boudoir. (Trans.)

Originally appeared in Cahiers du cinema April 1955, no. 46. This translation reprinted from Rivette: Texts and Interviews (British Film Institute, 1977): p. 54-64

6 ) 意大利之旅 (CINE FAN 2013) (寫於2013年7月23日)

【意大利之旅】是英格烈‧褒曼與導演 Roberto Rossellini 合作的五齣電影之一,故事圍繞一對婚姻瀕臨破裂的英國夫婦,在意大利遇見的人與事。電影雖有栗妹喜愛的英格烈‧褒曼,無奈男女主角那滿臉不耐煩的表情,實在太過難看,所以播了約15分鐘,已然進入半睡半醒的狀態。

好不容易等到電影播完,本想立即離開;但見主辦單位請了講者,心想既然電影看得不清不楚,就聽影後座談來個拉上補下吧,誰料竟聽出些趣味來。

講者先介紹女主角與導演之間的關係。原來英格烈‧褒曼為了 Rossellini 拋夫棄子,這跟英瑪‧褒曼的情況類似呢!不過今次的主人翁言語不通,比電影大師那一對又困難些。之後講者續道,Rossellini 拍電影,是邊拍邊改劇本的,這讓男女主角很不自在 (所以他們的表情才那麼臭!)。英格烈‧褒曼更說過,如果換成希治閣,肯定會破口大罵 (希治閣的準備功夫做得十分充足)。

同場有一位觀眾指出,導演可能想透過電影,諷刺英國人的死板沉悶。姑勿論導演的意圖為何,從文化的角度去看,這齣電影其實是挺有趣的,因為英國人跟意大利人的生活習慣,大大不同,文化衝擊十分明顯。

第一次發現,原來影後座談也可為電影添姿采。

IMDB:http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0046511/

豆瓣:http://movie.douban.com/subject/1303576/

意大利风景和歌谣都抵不住中产阶级内心的焦虑。丈夫夜归那场戏里的褒曼特写太美了,那个打光,全是来自导演的爱啊

看修复版还是被男女尸骸触动,到了某一刻你定会怀疑自己是否可以与身边的这个人一起死去,而怀疑最终变成恐惧和自省,结局是偶然还是注定。

三部曲部部完美,作为终章,不知是否在暗示褒曼和罗西里尼婚姻的走向?(他们正是结婚七年后宣布分手。)火山,废墟,残骸,博物馆… 这些代表着时间的东西,让爱情显得更加渺小、无处可寻。并且三部结尾都归于宗教,耐人寻味... 看完让人非常想去那不勒斯!

一起的时候厌倦,分开的时候恐惧,开始的时候期望结局,结束的时候又重新开始。 唯独像庞贝古城这样的遗憾,被火山湮灭,留住的只有刹那间人们的恐惧神情。

5.27 唯“爱情”没有出席。最后的复合更像是因为某种恐惧,看到自身的孤独,看到对方的孤独。实景之下,Cimitero delle Fontanelle和Pompeii都好美。

褒曼很可爱啊,就是那种高高的傻乎乎的姑娘,拿波里很好玩的样子。

#SIFF2014#四星半,为结尾的重合减半星;以夫妇对峙为切入口,反思战后伤痕,那累累的尸骨像沉重镣铐,永远桎梏着他们的良心;苦苦不肯放手地绝处逢生,彼此依赖相互折磨;通过宗教/信仰/自然/神迹的启迪,意识到人之渺小,达到自我超脱;观此片仿佛目睹褒曼与罗西里尼的真实生活,太虐。

喜欢达德利·安德鲁的这段评论:罗塞里尼在这部电影中让他那些扁平人物直面那不勒斯风景表层之下的历史积累。在“小维苏威”,凯瑟琳既困惑又欣喜地发现,她对着一个洞喷了一口烟后,她身边整块区域的地下会冒出一片烟雾。但在其他场合,她却不想与汽车挡风玻璃以外的世界发生任何联系。在博物馆,凯瑟琳从看起来栩栩如生的罗马雕像那里转身走开。在地下墓穴的发掘处,死者尸骨与那不勒斯市民共处,而她却转身走开。最后,她看到庞贝出土的一对拥抱着的夫妻的遗体,他们在1900年前被火山灰埋葬,像照片一样被永远定格,而这张照片正是在她面前显影的,此时,她在彻底的领悟所带来的痛苦中转身走开。影片结束于某种“奇迹”,这是一种神恩或爱情之潮,从另外一个层面如气球般涌入,疗救了一场残破的婚姻,即便这只是暂时的。

属罗西里尼风格转型期间的作品。影片中的街道多以实景拍摄,以热闹的街景反衬人物内心的荒芜,以冰凉的遗迹映照人物内心的焦躁。这部电影的叙事结构启发了安东尼奥尼的《女朋友》和费里尼的《甜蜜生活》的制作。这是罗西里尼电影中极为鲜明的现代意识,即一种展示人内心的“现实主义”。

“浮生若梦,为欢几何”。如果结婚8年,而且没有孩子,再来重看一遍。雅克·里维特认为这部电影开启了电影现代主义。具有高度的省略性,旅程的形式是褒曼饰演的角色同那不勒斯丰盛的生命(随处可见的孕妇和婴儿)以及更丰盛的死亡)葬礼、古尸挖掘、地下墓室)的一系列遭遇,汽车挡风玻璃和本地导游先后成为她与这一切之间的屏障,但最终她不得不直接面对。

7.6 《火山边缘之恋》的火山是爆发的,吞噬整个小岛;而《游览意大利》的火山却是温和的,岩浆缓流于地下,表明意大利最为艰苦的时期已过,家园重建已经完成,矛盾已非迫在眉睫,但精神上的枷锁仍然存在,就潜藏于十二英尺的地下。游览伴随着诡异音乐,一步步加重人的渺小与生命的易逝感,仿佛此时找到自己的位置就是最为严重的事情。当褒曼的面孔与大理石的面孔交替呈现的时候,生与死的历史就与活着的人共为一体,而终又要靠爱与生命拯救,一对夫妻和好了,圣母让那不勒斯充满了婴孩,是乐观还是批判?或许只是将缕缕光芒献给褒曼罢了。

战争中你流尽鲜血,和平中你寸步难行。

不知道为什么,罗西里尼的电影总给人异常真切的感觉。让人物陷入陌生的环境(不同的自然与人文景观),以此耗尽人物原先感官的能动性,以一个只接受声音与画面的身体而存在而不再向环境发散出自然的反射。感官的崩溃,极好地建立起纯粹的视听环境,于是乎,之于观众,是向角色的内化而不再是带入。

撇開年份不說,單就角色的塑造而言,是僵硬的﹔裡頭的義大利風光也沒好看到哪裡去,不知道怎會被如此吹捧?

真像安东尼奥尼,可这是54年的片。一道光的阴影,死去的恋人和褪温的诗。枯燥的旅行,犹疑不定的心。褒曼的一幕像有泪痕,细看是深深的轮廓,大银幕的美。结局如同“卡比利亚”的神迹。

参见前天《简奥斯丁书会》观感,这种经历了长久时间的婚姻最不需要的就是【意识】(反之是【tring】),而本片用了四分之三的时间为分别做铺垫,最后一刻却套用【意识】happy ending,我觉得如果写分开会更合适....不过这些都不重要了,重要的是我在大荧幕上看褒曼了啊!!!【花痴脸

《破碎的拥抱》里他们两人一起看的黑白电影就是这部,我想我知道了克鲁兹在沙发上为什么会哭

想要成为夫妻,就先去旅行一次。——无名氏

乔伊斯的《死者》在朴素、真实又极富文学性的《意大利之旅》里起着提纲挈领的作用。荷马叔叔代表的传统生活逝去之后,经历着现代式婚姻危机的上层中产夫妻来到了古典气息浓郁的意大利。而镜头里的意大利在时间层面上断裂为两层。一面是夫妻难以融入的普通人日常生活,未来对于他们是可以期待的,正如街头巷尾的妇女们都怀着孩子。另一面则是无数的博物馆和古迹,随着影片的进行,乔伊斯中篇里的雪在这里演变成维苏威的火山灰,把夫妻俩的爱情一点一点地活埋。这样看来,影片最后突然发生的和解不能从字面意上理解。爱情已经死亡,但孤独对他们而言实在不可接受,最终的拥抱发生在两具行将就木的尸体之间,好在庞贝城毁灭之际,至少给未来的考古学家留下一个相爱的假象。

罗西里尼的褒曼和希区柯克的褒曼简直是判若两人……虽然罗西里尼不是我的菜 但经常能从他的电影中看到一些神来之笔