详细剧情

突然之间,特里发现自己被卷入了十分危险的事件中去,来自某个神秘人物的追杀更加让他下定了要追查到底的决心。他知道,真相永远隐藏在巨大的权利背后,而自己随时都面临着生命危险,在这样动荡的环境下,能够相信的只有自己。

长篇影评

1 ) 《凶线》:我要你心底的恨

Q:关于录音的电影不少。

L:是啊,《窃听风暴》、黑泽清的《降灵》、科波拉的《对话》,很牛逼;许秦豪的《春逝》、《鬼信号》,也算不错。因此,对录音题材的电影,首先,我兴趣很大,其次,我期望也比较高。

Q:这部《凶线》如何?

L:相当失望。想不通CC为什么要收这部片子。首先,戏剧张力不足,剧情过于拖沓,人物行为趋势明显,却扭扭捏捏,总是顾左右而言他;其次,人物塑造不力,男女主角都不丰满,反面角色也相当单薄,以侧面表现为主的反动政治势力,也只是点到为止,一点儿都不深刻。最后,一些象征,比如结尾在美国国旗下男主角杀掉杀手,过于直白,生怕观众看不出来。你看片子无趣到什么地步,我说的首先其次最后,都想不起个具体例子,只剩下看片时的观感。

Q:原因何在呢?

L:主创对政治肯定不熟悉,看得出,他既想涉及政治,又底气不足,不敢着力表现,导致政治在这部片子里,背景不是背景,总是打断叙事,主线不是主线,一直断断续续。这种片子,要么就让政治纯属作为背景,重点去探讨不变的人性,就像《窃听风暴》和科波拉的《对话》,要么就让凶杀案作为引子,着力揭露政治的黑暗与龌龊,像奥利弗·斯通的《JFK》、《尼克松》。

Q:看来还是要拍自己熟悉的对象。

L:熟悉只是基本前提,最关键是要有感情:如果你热爱政治,你可以去拍“歌德派”电影,当然真挚不真挚谁都看得出来;如果你憎恶政治,那就把你心底里的憎恶拍出来。就情感来说,艺术,必须要有极致的情感,哪怕是冷漠,也得是极致的冷漠。

2 ) pauline-kael的评论

转载于://scrapsfromtheloft.com/2018/07/17/blow-out-pauline-kael/

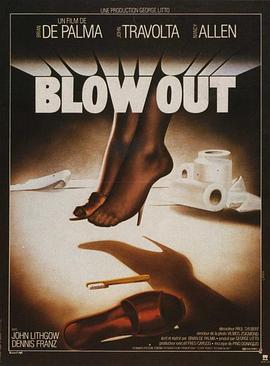

At forty, Brian De Palma has more than twenty years of moviemaking behind him, and he has been growing better and better. Each time a new film of his opens, everything he has done before seems to have been preparation for it. With Blow Out, starring John Travolta and Nancy Allen, which he wrote and directed, he has made his biggest leap yet. If you know De Palma’s movies, you have seen earlier sketches of many of the characters and scenes here, but they served more limited—often satirical—purposes. Blow Out isn’t a comedy or a film of the macabre; it involves the assassination of the most popular candidate for the presidency, so it might be called a political thriller, but it isn’t really a genre film. For the first time, De Palma goes inside his central character—Travolta as Jack, a sound effects specialist. And he stays inside. He has become so proficient in the techniques of suspense that he can use what he knows more expressively. You don’t see set pieces in Blow Out—it flows, and everything that happens seems to go right to your head. It’s hallucinatory, and it has a dreamlike clarity and inevitability, but you’ll never make the mistake of thinking that it’s only a dream. Compared with Blow Out, even the good pictures that have opened this year look dowdy. I think De Palma has sprung to the place that Altman achieved with films such as McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Nashville and that Coppola reached with the two Godfather movies—that is, to the place where genre is transcended and what we’re moved by is an artist’s vision. And Travolta, who appeared to have lost his way after Saturday Night Fever,makes his own leap—right back to the top, where he belongs. Playing an adult (his first), and an intelligent one, he has a vibrating physical sensitivity like that of the very young Brando.

Jack, the sound effects man, who works for an exploitation moviemaker in Philadelphia, is outside the city one night recording the natural rustling sounds. He picks up the talk of a pair of lovers and the hooting of an owl, and then the quiet is broken by the noise of a car speeding across a bridge, a shot, a blowout, and the crash of the car to the water below. He jumps into the river and swims to the car; the driver—a man—is clearly dead, but a girl (Nancy Allen) trapped inside is crying for help. Jack dives down for a rock, smashes a window, pulls her out, and takes her to a hospital. By the time she has been treated and the body of the driver—the governor, who was planning to run for president—has been brought in, the hospital has filled with police and government officials. Jack’s account of the shot before the blowout is brushed aside, and he is given a high-pressure lecture by the dead man’s aide (John McMartin). He’s told to forget that the girl was in the car; it’s better to have the governor die alone—it protects the family from embarrassment. Jack instinctively objects to this cover-up but goes along with it. The girl, Sally, who is sedated and can barely stand, is determined to get away from the hospital; the aide smuggles both her and Jack out, and Jack takes her to a motel. Later, when he matches his tape to the pictures taken by Manny Karp (Dennis Franz), a photographer who also witnessed the crash, he has strong evidence that the governor’s death wasn’t an accident. The pictures, though, make it appear that the governor was alone in the car; there’s no trace of Sally.

Blow Out is a variation on Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966), and the core idea probably comes from the compound joke in De Palma’s 1968 film Greetings: A young man tries to show his girlfriend enlarged photographs that he claims reveal figures on the “grassy knoll,” and he announces, “This will break the Kennedy case wide open.” Bored, she says, “I saw Blow-Up—I know how this comes out. It’s all blurry—you can’t tell a thing.” But there’s nothing blurry in this new film. It’s also a variation on Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), and it connects almost subliminally with recent political events—with Chappaquiddick and with Nelson Rockefeller’s death. And as the film proceeds, and the murderous zealot Burke (John Lithgow) appears, it also ties in with the “clandestine operations” and “dirty tricks” of the Nixon years. It’s a Watergate movie, and on paper it might seem to be just a political melodrama, but it has an intensity that makes it unlike any other political film. If you’re in a vehicle that’s skidding into a snowbank or a guardrail, your senses are awakened, and in the second before you hit, you’re acutely, almost languorously aware of everything going on around you—it’s the trancelike effect sometimes achieved on the screen by slow motion. De Palma keeps our senses heightened that way all through Blow Out; the entire movie has the rapt intensity that he got in the slow-motion sequences in The Fury (1978). Only now, De Palma can do it at normal speed.

This is where all that preparation comes in. There are rooms seen from above—an overhead shot of Jack surrounded by equipment, another of Manny Karp sprawled on his bed—that recall De Palma’s use of overhead shots in Get to Know Your Rabbit (1972). He goes even further with the split-screen techniques he used in Dressed to Kill (1980); now he even uses dissolves into the split screen—it’s like a twinkle in your thought processes. And the circling camera that he practiced with in Obsession (1976) is joined by circling sound, and Jack—who takes refuge in circuitry—is in the middle. De Palma has been learning how to make every move of the camera signify just what he wants it to, and now he has that knowledge at his fingertips. The pyrotechnics and the whirlybird camera are no longer saying “Look at me”; they give the film authority. When that hooting owl fills the side of the screen and his head spins around, you’re already in such a keyed-up, exalted state that he might be in the seat next to you. The cinematographer, Vilmos Zsigmond, working with his own team of assistants, does night scenes that look like paintings on black velvet so lush you could walk into them, and surreally clear daylight vistas of the city—you see buildings a mile away as if they were in a crystal ball in your hand. The colors are deep, and not tropical, exactly, but fired up, torrid. Blow Out looks a lot like The Fury; it has that heat, but with greater depth and definition. It’s sleek and it glows orange, like the coils of a heater or molten glass—as if the light were coming from behind the screen or as if the screen itself were plugged in. And because the story centers on sounds, there is a great care for silence. It’s a movie made by perfectionists (the editor is De Palma’s longtime associate Paul Hirsch, and the production design is by Paul Sylbert), yet it isn’t at all fussy. De Palma’s good, loose writing gives him just what he needs (it doesn’t hobble him, like some of the writing in The Fury), and having Zsigmond at his side must have helped free him to get right in there with the characters.

De Palma has been accused of being a puppeteer and doing the actors’ work for them. (Sometimes he may have had to.) But that certainly isn’t the case here. Travolta and Nancy Allen are radiant performers, and he lets their radiance have its full effect; he lets them do the work of acting too. Travolta played opposite Nancy Allen in De Palma’s Carrie (1976), and they seemed right as a team; when they act together, they give out the same amount of energy—they’re equally vivid. In Blow Out, as soon as Jack and Sally speak to each other, you feel a bond between them, even though he’s bright and soft-spoken and she looks like a dumb-bunny piece of fluff. In the early scenes, in the hospital and the motel, when the blonde, curly-headed Sally entreats Jack to help her, she’s a stoned doll with a hoarse, sleepy-little-girl voice, like Bette Midler in The Rose—part helpless, part enjoying playing helpless. When Sally is fully conscious, we can see that she uses the cuddly-blonde act for the people she deals with, and we can sense the thinking behind it. But then her eyes cloud over with misery when she knows she has done wrong. Nancy Allen takes what used to be a good-bad-girl stereotype and gives it a flirty iridescence that makes Jack smile the same way we in the audience are smiling. She balances depth and shallowness, caution and heedlessness, so that Sally is always teetering—conning or being conned, and sometimes both. Nancy Allen gives the film its soul; Travolta gives it gravity and weight and passion.

Jack is a man whose talents backfire. He thinks he can do more with technology than he can; he doesn’t allow for the human weirdnesses that snarl things up. A few years earlier, he worked for the police department, but that ended after a horrible accident. He had wired an undercover police officer who was trying to break a crime ring, but the officer sweated, the battery burned him, and, when he tried to rip it off, the gangster he hoped to trap hanged him by the wire. Yet the only way Jack thinks that he can get the information about the governor’s death to the public involves wiring Sally. (You can almost hear him saying “Please, God, let it work this time.”) Sally, who accepts corruption without a second thought, is charmed by Jack because he gives it a second thought. (She probably doesn’t guess how much thought he does give it.) And he’s drawn to Sally because she lives so easily in the corrupt world. He’s encased in technology, and he thinks his machines can expose a murder. He thinks he can use them to get to the heart of the matter, but he uses them as a shield. And not only is his paranoia justified but things are much worse than he imagines—his paranoia is inadequate.

Travolta—twenty-seven now—finally has a role that allows him to discard his teenage strutting and his slobby accents. Now it seems clear that he was so slack-jawed and weak in last year’s Urban Cowboy because he couldn’t draw upon his own emotional experience—the ignorant-kid role was conceived so callowly that it emasculated him as an actor. As Jack, he seems taller and lankier. He has a moment in the flashback about his police work when he sees the officer hanging by the wire. He cries out, takes a few steps away, and then turns and looks again. He barely does anything—yet it’s the kind of screen acting that made generations of filmgoers revere Brando in On the Waterfront: it’s the willingness to go emotionally naked and the control to do it in character. (And, along with that, the understanding of desolation.) Travolta’s body is always in character in this movie; when Jack is alone and intent on what he’s doing, we feel his commitment to the orderly world of neatly labeled tapes—his hands are precise and graceful. Recording the wind in the trees just before the crash of the governor’s car, Jack points his long, thin mike as if he were a conductor with a baton calling forth the sounds of the night; when he first listens to the tape, he waves a pencil in the direction from which each sound came. You can believe that Jack is dedicated to his craft because Travolta is a listener. His face lights up when he hears Sally’s little-girl cooing; his face closes when he hears the complaints of his boss, Sam (Peter Boyden), who makes sleazo “blood” films—he rejects the sound.

At the end, Jack’s feelings of grief and loss suggest that he has learned the limits of technology; it’s like coming out of the cocoon of adolescence. Blow Out is the first movie in which De Palma has stripped away the cackle and the glee; this time he’s not inviting you to laugh along with him. He’s playing it straight and asking you—trusting you—to respond. In The Fury, he tried to draw you into the characters’ emotions by a fantasy framework; in Blow Out, he locates the fantasy material inside the characters’ heads. There was true vitality in the hyperbolic, teasing perversity of his previous movies, but this one is emotionally richer and more rounded. And his rhythms are more hypnotic than ever. It’s easy to imagine De Palma standing very still and wielding a baton, because the images and sounds are orchestrated.

Seeing this film is like experiencing the body of De Palma’s work and seeing it in a new way. Genre techniques are circuitry; in going beyond genre, De Palma is taking some terrifying first steps. He is investing his work with a different kind of meaning. His relation to the terror in Carrie or Dressed to Kill could be gleeful because it was pop and he could ride it out; now he’s in it. When we see Jack surrounded by all the machinery that he tries to control things with, De Palma seems to be giving it a last, long, wistful look. It’s as if he finally understood what technique is for. This is the first film he has made about the things that really matter to him. Blow Out begins with a joke; by the end, the joke has been turned inside out. In a way, the movie is about accomplishing the one task set for the sound effects man at the start: he has found a better scream. It’s a great movie.

The New Yorker, July 27, 1981

3 ) 男主角太装B了,一切都不在掌控中

装B装大了,复合约翰·屈伏塔一贯的角色设定。

4 ) 恐怖片真实的临死尖叫

5 ) 《凶线》:从镜头语言浅析影片

该影片的叙事线索为两条线,一条是与主人公身份相关的尖叫声,另一条则是与凶杀案故事相关的钩子拉线声。这两条线索首尾呼应,在片中偶有穿插,使影片结构更紧凑,叙事条理清晰。

导演布莱恩·德·帕尔玛在该影片中镜头语言运用极为丰富,运镜长镜头居多,运动镜头在影片中处处可见。如在卡普尔家中,摄影机用移镜头展现卡普尔家脏乱的环境以及他的生活状态直到敲门声响起;莎丽与特里通话时镜头后拉下移到地下展现凶手;莎丽和特里在车中亲吻告别后镜头拉近到楼上的凶手,运镜拍其擦鞋子上的血迹,再用跟镜头展现凶手的运动轨迹后移动镜头聚焦到留下莎丽走进车站,全程一气呵成,没有台词但是镜头语言交代的信息量大,不仅交代了人物的关系和意图,还有周围环境与事情发现状况。在影片后段特里的“最后一分钟营救”过程中多用升格镜头,增加紧张感,也突出特里的勇敢与伟大,同时,将特里的狂奔乱撞的惊慌与着急,与街道上庆祝自由日的人群的欢乐与雀跃形成鲜明对比,在嘈杂人群中特里的逆流而上与升格镜头的结合显得格外带有悲剧色彩。当嘈杂声渐渐被悲壮的音乐取代,随着音乐的推动逐渐将影片引向高潮。当特里发现莎丽已经死了之后,单人固定镜头中,红蓝白单色光影与阴影交替变换,突出人物内心的痛苦。特里抱着莎莉时使用仰拍旋转镜头,将背景对准天上的烟花,进一步升华了人物形象,体现主角为了真相无畏而勇敢的伟大举动,即使做出牺牲,但杀死了凶手,保留了真相,在一定意义上也是一种成功,烟花歌颂他们的伟大也庆贺他们的成就。

影片中的色彩主要以红蓝为主,既呼应了美国国旗,体现美国自由日的故事背景,也不断用红色的出现反应危险的存在。整部影片霓虹灯多,色彩浓郁,饱和度较高,比较经典的美国电影色调,偏暗的色调体现凶杀案的沉重与迷离、凶手与真相的隐藏,增加影片神秘感。

影片中特写镜头少,均应用于关键转折或线索中,如特里录音麦克风、杂志上的照片、凶手的眼睛、手套和勾绳等等,大部分交代故事发展以中远景为主,将人物置于人群等大环境中(如医院、车站等),使画面丰富,故事感强,增加真实感。

结合影片主人公特里职业的特殊性,并片中声音与画面的结合尤为巧妙。声音的巧妙成为了某些暗喻或凶杀案的线索,影片中多用声音传达信息,尤其是电视的运用,交代故事背景也交代事情结果。各种声音也为影片制造悬念。

6 ) 完美尖叫

政治惊悚片。帕尔马总有富有创造力的镜头,这部片子中的裂焦镜头多而精妙,Jake和猫头鹰、Jake听到警察和官员谈话、死鱼和女性受害者,都是非常精湛的构图。Jake在工作室里找录音带那一段9*360°的旋转镜头令人印象深刻。Jake在烟花下抱住妓女尸体的镜头明明很俗套,却拍出了超乎常人的美感。 剧作的开端很抓人,一名电影音效师,在桥上采集素材时偶然捕捉到州长开车落水前的枪响,又下水救了车里的妓女。政治迫害和州长召妓的秘密就这样偶然被Jake发觉,而召妓其实也是对手雇佣摄影师曼尼·卡普和妓女设下的圈套。Jake剪下杂志刊登的卡普拍摄的车祸照片,与录音拼凑成了完整证据,且发觉了照片中微微一抹疑似枪械的银光。而敌对势力则抹除了Jake的原录音,并时刻准备除掉三个知情人,销毁全部证据。 竞选对手其实内部不合,原方案是制造召妓丑闻取回照片,但组织中的杀手却擅自行事,直接了解了州长的姓名。杀手善后的手段很老道,偷换了事故车辆上中弹的轮胎,用爆胎混淆视听。为了做掉妓女并掩盖其真实死因,提前连杀两名具有相似体貌特征的女性,再用公用电话报警“自白”,伪造成连环杀手。最后冒充电视主持人,以协助公开真相为由约出妓女,把证据扔进湖里销毁后,在独立日游行的国旗下行凶。虽被及时赶到的Jake反杀,但Jake也永远失去了公开真相的机会。 妓女临死前的真实尖叫成为了新片中正需要的声音素材,而Jake也只能听着妓女临死前的录音怀念亡者,在剪辑室里抽着烟自嘲:真是完美的尖叫啊。

德·帕尔玛媒介自反最好的一部。此前Blow-up讲过了画面,Conversation又讲了声音,本片的巧思之处在于,从声音切入来讲声画的同步。从而将一个后肯尼迪之死时代的政治阴谋故事,嫁接到电影的后期制作过程上,继而达成一个漂亮的元电影回环。

本片可谓迷影堆彻类作品中成就最高的一部。河边录音和简报成影等几段专业操作实在太酷了!虽然观者已知创意源头来自安东的放大和科波拉的大窃听但丝毫不影响我们对它的欣赏和喜爱。另个重要迷影源头当然是希区柯克。投河救人的第一次与拯救失败的第二次显然照搬迷魂记。但个人对于用高调悬念手法(观众全知而角色不知)去处理最后一幕持保留看法。希区曾解释自己的悬念错用:过于残酷让小男孩被炸死,并非错误症结的所在。真正败笔在于观众的紧张情绪没有得到有效释放。在他们已知炸弹被带上了车,也知炸弹可能在几点爆炸的情况下,唯一合理的悬疑终结手段就是让炸弹被发现并被转移到安全处引爆。换句话说,此处情节设计虽然很写实,但却破坏了悬念的结构,没有满足和调动观众正常的心理需求……男孩之于炸弹如此,莎莉之于拯救也应是如此!三星半。

#蓝光重刷计划# 布莱恩·德·帕尔玛接过希区柯克的衣钵,看到不少致敬大师的影子,同时也把自己的风格发挥到的淋漓尽致,我倒是很爱这种留白式做减法的叙事,比如最后那个“最棒的尖叫”,更让人觉得意味深长。

整体看来,味道很怪,有希区柯克的味道,但有不仅限于希区柯克,凶杀氛围营造的很赞,很有味道,故事层层递进,但是有点闷,最后来个前后呼应,也算文章平淡做法。看到最后,在那漫天烟花下,男主角抱着死去的女主角失声痛哭时,让我给这部电影加上了爱情的标签

惊魂记浴室尖叫,西北偏北俯拍,夺魂索布假景,窃听大阴谋窃听,“放大”声音。这些他者印记加上开头戏中戏长镜和九圈360度长镜,以及野外录音剪辑处理,技巧让人跪服。故事依旧是由技术复制时代对人的异化起,但没有达到期待高度。从寻找尖叫到想摆脱尖叫,楼顶烟火忆起新桥恋人。

从《放大》到希区柯克,精彩的环节还是在的,甚至前--六分之五都很好啊,但是最后部分突然搂不住了是怎么回事,拍high了吗?满溢的配乐,汹涌的情感,都让我招架不住啊。。。(另外豆瓣这个又名: 爆裂剪辑 是怎么回事。。。

35mm Im crying... absolutely amazing QAQ (每次进入没有办法100%认真看片 焦虑/轻度抑郁 学术没有心思的时候就把高潮戏翻出来看一遍 每次都会有想大哭一场的程度 以后再被问到最喜欢的电影是什么 就是这部了 无法取代了暂时)

3+...考虑到出产年份,这片还是很高质量大制作的...大家都推崇烟火场景,我倒觉得上帝视角拍屈伏塔开车穿过一片古建筑更有感...

simplistic hollywood remake of Antonioni's Blow up. It does has it's moments though.

拼接希区柯克,奥菲尔斯,科波拉,安东尼奥尼各个的一部分,放置到自我感动的故事里,真是帕尔马的平实优点和缺点,那个旋转的长镜头确实很炫......

他妈的,居然是转圈长镜头

De Palma对剪辑、摄影、配乐、音响等技法的运用出色至极,开场的段落给人一种惊艳之感!而结尾与开头的呼应也使影片更令人回味。

技法依旧神乎其神,印象最深的是听录音时通过主观视角拼贴还原案发事件,以及那个N圈的旋转镜头。音乐是败笔,无处不在的配乐塞得太满了,既然有那么牛逼的镜头语言实在没必要再靠这一招渲染气氛和情绪,少而精才是王道,成功之例可见于《惊魂记》。高潮部分慢镜+去掉背景音也有些肉麻了。

和所有的“迪庞马”片的毛病一样:虎头蛇尾。开篇slasher/giallo的致敬惊艳,“谜题”的铺陈设置貌似妙笔连连,到现象的重构时有趣的细节已被抛弃,最终的解决只能用“导演在找借口结束本片"来解释。和模仿对象Blow Up比较两片的结构完全一样,只不过一个是上坡一个是下坡

太厉害!虽然剧情和立意有点弱,但瑕不掩瑜,从技术层面来看简直棒呆,太开眼,调度、运镜、构图…快要玩出花来了,不拘一格,各种炫目和惊叹,特拉沃尔塔口音太重了,一听便知,论声效的重要性,最真实的反应源于惨烈可怖的现实体验,绝妙的呼应和衔接,又一个神结尾,为帕尔玛的硬实力献上膝盖。

四星半,偷师希区柯克和安东尼奥尼,德帕尔马是新好莱坞中最娴熟的改装主义者、技术控达人。強烈且可感知的摄影机存在,凶杀场面是典型的希区柯克在场,双屏、剪辑、音效、长摇镜头等等,不遗余力的改造强化电影的表现力,把旧有的类型和题材重新包装改造,加入更加现代的视角和技法融入到整个叙事当中。他从过去抵达现代。

华丽的技巧,十足的紧张感,开场戏中戏两个帕尔玛最拿手的长镜拼贴,结局烟花灿烂与斯人已逝的对比,一个原本普通的故事被打造得足够精彩。

感觉那个时期的布莱恩·德·帕尔玛电影都是剧本和故事很普通,但是技术很牛逼。

拍摄手法传承希区柯克,情节及节奏则有Blow-up的影子。剪辑、配乐和镜头设计都极有看头。缺点在于影片的形式远大于内容,人物二维化,表演脸谱化,以致结尾失连,前后情绪脱节。

1.录音师的真相求索之路,悬疑惊悚版[放大]。2.帕尔玛的镜头调度令人着迷,如片首戏中戏的杀手主观长镜、剪辑室9圈旋转长镜及大量大俯角镜。3.浴室尖叫致敬[精神病患者],高潮以脸上映照的烟花五彩闪光彰显惶惑凄楚心境,同质于[夺魂索]。4.地铁追逐戏如[情枭的黎明]预演。5.大桥收音分镜。(8.5/10)