更新时间:2024-04-13 01:38

详细剧情

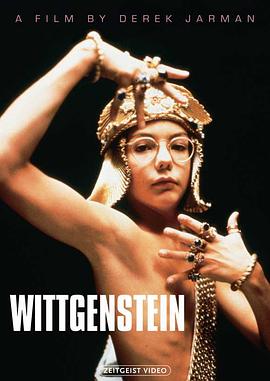

这是一部现代风格的戏剧,介绍了生于维也纳,在剑桥读书的哲学家Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951)的生平及思想。他的主要兴趣在于研究语言的本质与极限。 电影使用最简单的黑色背景,所有的投资都用在服装、演员以及灯光上,构图就像黑暗的启蒙主义绘画。Wittgenstein以一个小男孩的形象出现,他的少年时代很压抑,银幕上他的家人都身穿罗马人的宽外袍。一系列的小场景描述了他从小时候,到第一次世界大战,再到最终在剑桥当教授和Bertrand Russell以及John Maynard Keynes合作的生平。导演Derek Jarman使用了一些戏剧小品,还有富于想象力的小花招,比如出现了火星侏儒,来表现Wittgenstein的贵族举止,犹太背景,以及同性恋倾向。

长篇影评

1 ) Philosophers and Queers

-Are you philospher?

-Yes, I am.

-Are you happy?

-......(slience)

-You know. You really shoul give it up.

Get out while you still can.

That's what Wittgenstein tells Jonny at their fist meet.

-I'd quite like to have composed a philosphical work which consisted entirelly of jokes.

-Why didn't you?

-Sadly, I didn't have that sense of humour.

That's what Wittgenstein say when extremely close to death.

I love queers, especially handsome queers, like Wittgenstein. It's really pityful that the actor who plays him in the film isn't, but his lover, Johnny is. It seems that the image of philopher is always so crazy, miserable, misunderstandable. Well, maybe it's also the deep image of Derek Jarman himself. Queers are prodigies, who can't be understood by the world.

Why I chose the two diaglogue is that philosphers seem to be tradgic and philosphy is pretty ridiculous while we've been strongly attracted by it and can't help dying for it.

-Yes, I am.

-Are you happy?

-......(slience)

-You know. You really shoul give it up.

Get out while you still can.

That's what Wittgenstein tells Jonny at their fist meet.

-I'd quite like to have composed a philosphical work which consisted entirelly of jokes.

-Why didn't you?

-Sadly, I didn't have that sense of humour.

That's what Wittgenstein say when extremely close to death.

I love queers, especially handsome queers, like Wittgenstein. It's really pityful that the actor who plays him in the film isn't, but his lover, Johnny is. It seems that the image of philopher is always so crazy, miserable, misunderstandable. Well, maybe it's also the deep image of Derek Jarman himself. Queers are prodigies, who can't be understood by the world.

Why I chose the two diaglogue is that philosphers seem to be tradgic and philosphy is pretty ridiculous while we've been strongly attracted by it and can't help dying for it.

2 ) Derek Jarman’s Personal Narrative

我很少看把电影看第二遍……但这部传记片实在是太有趣了。

对于大众来说为什么牛逼:

成本低,概念高。演员也都选得好

而导演Jarman也是很下功夫。当时几近失明的他,把维老他的人和他的思想都读透了。改写剧本时Jarman大胆想象,写成了这么一部轻松诙谐加自我调侃的同志哲人传记片。我就喜欢这种先锋的自我解读,而不是循规蹈矩走传统传记路线。

对于我个人来说为什么牛逼:

感情呈现的起乘转折的节奏把握得特别好。不乏感人的台词,尤其是结尾凯恩斯的那段独白比喻,听得心都融化了。

我和片中偏执地寻找『私人语言』维老有同感。时常在个人的孤独感中纠结与人交流时所遇到的困难。

他认为 解决这种孤独 尤其是哲人的孤独(brooding over its private experience) 的方式就是寻找公共语言

而完善这种语言的方式就是让所有人的逻辑体系都是理性的、一致的。

当有人对他做侮辱手势的时候,他开始意识到,人类的语言不可能完美。

他执着而天真 聪明而钻牛角尖 不爱都不行。

好吧其实是为了贴作业的,调研贾曼的两部电影

中心论点在第一段。。关于电影中的同志题材和场景设置

Derek Jarman’s Personal Narrative—Exploring Ludwig Wittgenstein and Michelangelo Caravaggio’s Brilliance and Queer Identities

As one of the best-known British queer directors, Derek Jarman produced several unique biopics of talented men tortured by their repressed homosexuality. Notably, Jarman started his career in feature film by working with Ken Russell, a director who reinvented the artist biopic by “introducing startling fantasy sequences and ostentatious camera movements.” Jarman continued Russell’s revolt against conventional realist representation of historical figures. Also using biopics as a form of documentation, Jarman has sought to reenact experience and thereby reconstruct affective relations. He identifies with brilliant queer men who are often too radical for their times. By portraying queer figures, Jarman interprets art and philosophy as well as repressed emotions and loneliness of queer men. Even during the conservative periods, Jarman’s nuanced films carried many provocative themes that were not only political but also highly personal. Caravaggio (1986) and Wittgenstein (1993) exemplify these aspects of Jarman’s individualistic, subjective approach. Jarman admits to strongly identifying with Wittgenstein: “I have much of Ludwig in me. Not in my work, but in my life.” Jarman has also stated in interviews that his artistic dilemmas are similar to those experienced by Caravaggio. This research paper attempts to capture the richness of Jarman's personal relationship with these two figures by discussing both films’ use of mise-en-scene and their thematic concern with queer identity.

Jarman engages with the lives of Wittgenstein and Caravaggio by referencing and paying homage to their work on a theoretical level. A painter and former set designer, Jarman emphasizes the use of mise-en-scene as substitute for literal narrative. In Jarman's films, staging and visual imagery are the most important qualities, while “narrative takes second place". While the lack of emphasis on logical narrative granted him more space to experiment, viewers with little knowledge of the characters are often confused. Jarman concentrates on constructing the plot around Caravaggio's paintings rather than his life and times. Critics have pointed out the absence of a clear narrative in Caravaggio. The characters and their relations to Caravaggio are unclear and sometimes misleading. Many supporting characters do not have presence in the plot that was fully distinct from their respective paintings. Yet Jarman believed he had to establish a unique perspective in order to capture Caravaggio’s dramatic “Hollywood template” life in a 90-minute film without resorting to clichés. Narrative ambiguity allows Jarman to “recreate many details of [his] life and, bridging the gap of centuries and cultures, to exchange a camera with a brush.” He interweaves the paintings with the plot with a painstakingly reworked script that involved 16 rewrites, as well as magnificent tableaux vivant production sets. Jarman focuses on Caravaggio’s emotions, sexuality, dreams and events surrounding the creation of his paintings, redefining the genre of the artist biopic. The paintings drive the narrative, and the consciousness depicted is not that of independently conceived characters but that of the artist himself, Jarman-Caravaggio.

As a lifelong painter, Jarman appreciates the narrative power of mise-en-scene and highlights it in the set designs for both films. Jarman is fascinated by Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro to create the illusion of depth. He praised Caravaggio for inventing cinematic light and the noir style shadowed backgrounds. Jarman pays homage to this technique through tightly controlled lighting effects. The tone and shade of the walls and skin color convey more about the scene than the script. In most scenes, Jarman meticulously replicates Caravaggio’s light sources, which usually come from the left and therefore elicits stronger responses from the viewers. Jarman attempts to show that the chiaroscuro is effective to capture intense emotions not only on canvas but also in film. He pays homage to Caravaggio by employing light and emphasizes the timelessness of classic art techniques.

While Jarman painted cinema like the artist Caravaggio, he also philosophized it, as expressed in the mise-en-scene of Wittgenstein. Jarman portrays Wittgenstein’s general estrangement from a painfully foreign world as a result of both his abstract philosophy and his difficulties accepting his sexuality. Jarman shows a world that appears absurd from Wittgenstein’s perspective: the highly stylized acting and flamboyant costumes of other characters contrast with Wittgenstein’s naturalistic acting and gray tweed jacket. Wittgenstein questions himself throughout the film: “How can I be a logician before I am a human being? The most important thing is to settle accounts with myself!” He travels across Europe, fighting in the Great War, teaching in a rural school, and escaping to Ireland or Norway to familiarize himself with the strange world, yet its meaning is still “problematic.” Wittgenstein, troubled by his sexuality, also wished to live an ethical life guided by strict logic. Yet this longing for perfection is disrupted by the messiness of life and the fickleness of passions.

Jarman places symbolic visuals in the biopic, which remind sophisticated audiences of “Wittgenstein’s epigrammatic style” of writing. Lady Ottoline paints Bertrand Russell on canvas as a red monochrome. When he wrote the script, Jarman also tried to understand Wittgenstein’s personal life by reading his books. Remarks on Colour provided him with cinematic context to relate to Wittgenstein’s ideas: “Remarks on Colour was a path for me back to the Tractatus [Logico-Philosophicus].” Furthermore, Jarman’s schematic use of color contrasts between the repression of private feelings and the expression of straightforward colors. "The black annihilates the decorative and concentrates so my characters shine in it like red dwarfs—and green giants. Yellow lines and blue stars”, Jarman references the schematic use of colors in Wittgenstein poetically. Jarman later wrote an entire book—Chroma— to show how colors are solely products of human interaction. In Wittgenstein’s words: “I think that it is worthless and of no use whatsoever for the understanding of painting to speak of the characteristics of the individual colours.” Through referencing Wittgenstein’s ideas on colors in the mise-en-scene as well as script text, Jarman pays homage to the philosopher. Jarman also successfully uses film medium to explore abstract theories and overcomes limitations of language.

Jarman engages with Wittgenstein and Caravaggio not only on a theoretical level but also reads into their personal struggles with homosexuality. Similar to abstract theories, Jarman’s Wittgenstein believed that homosexuality is an area that restricts language as a mode of expression. “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent,” Wittgenstein once wrote. In Jarman’s dialogue and cinematography, Wittgenstein's struggles to come to terms with his own philosophical ideas were inseparable from his attitude towards his sexuality. In one scene, three cyclists dressed in anachronistic jumpsuits abuse him with homophobic slurs and the insulting V-sign. Wittgenstein is flabbergasted and realizes there is no “logical structure” in the V-sign – the main argument of his first book. He plans to commit suicide but then rethinks his entire philosophy of language, completing his magnum opus Philosophical Investigations. Wittgenstein is confused by the logic of a curse, but Jarman sets the scene to suggest that Wittgenstein is confounded by homophobia. Jarman explains that Wittgenstein found a black hole in the logic, “for [the picture of Queer] there was no language.” Later, Bertrand Russell is infuriated after Wittgenstein convinces his student Johnny to work and drives him away from philosophy. Russell criticizes Wittgenstein for idealizing the common folk and “infecting too many young men” with his thought experiments. Jarman hints at Wittgenstein’s homosexual relationships with students through these double entendres. Wittgenstein's euphemisms, too, reflect his embarrassment concerning these relationships: He has “known” Johnny three times. Following this scene, Jarman places the mentally tormented Wittgenstein in a suspended cage. Wittgenstein ponders upon his relationships with his university and exclaims painfully: “Philosophy is the sickness of the mind. I mustn’t infect too many young men… living in a world where such a love is illegal and trying to live openly and honestly is a complete contradiction.” John Maynard Keynes, also clearly homosexual in the film, consoles Wittgenstein: “If you’d just allow yourself to be a little more sinful, you’d stand a chance of salvation.” Both Wittgenstein’s sexuality and philosophy alienates him from the real world. Jarman portrays a Wittgenstein who finds it difficult to distinguish between his philosophy and sexual passions.

Similarly, Jarman regards Caravaggio as the most homosexual of painters, based on his paintings rather than his biography. Jarman notes that Caravaggio paints his own face staring from the back of the crowd in The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew. He hypothesizes that “[Caravaggio] gazes wistfully at the hero slaying the saint. It is a look no one can understand unless he has stood till 5 a.m. in a gay bar hoping to be fucked by that hero. The gaze of the passive homosexual at the object of his desire, he waits to be chosen, he cannot make the choice”. Jarman reads Caravaggio's paintings for insights into his psychology and romantic relationships, and places these readings into his film. Caravaggio suffers creative drought while painting The Martyrdom. He encounters the attractive, masculine yet poor Ranuccio and selects him as a model. Ranuccio, the object of desire, inspires Caravaggio to finish the painting. Caravaggio showers him with gold coins in a suggestive fashion and also delivers one of the coins mouth to mouth. At the final stage, Caravaggio gazes intensely at Ranuccio still posed as the Martyr, forming a tableau vivant of the painting. His role as the artist desiring for Caravaggio and man yearning for St. Matthew in the painting is blurred. Caravaggio says in a voiceover, “I will seek him, whom my soul loves. I sought him, but found him not.” Jarman depicts Caravaggio as having romantic yet passive sentiments for the undesirable and shows this through ingenious mise-en-scene.

Elsewhere, Jarman portrays Caravaggio’s passivity as a product of the hypocrisy of the Roman Catholic establishment’s homophobia. He reads in the same painting “pernicious self-hatred [homosexuals] fostered among themselves… which is the key to Caravaggio’s life and destruction—it’s written all over the painting.” Jarman also identifies many of Caravaggio’s paintings as claustrophobic. Believing that there is a connection between Caravaggio’s style and his state of mind, Jarman films all of the scenes in studio with claustrophobic environments to suggest Caravaggio’s suffocation in a homophobic society. There is only one exterior scene in Caravaggio, in which Ranuccio and Lena are engaging in heterosexual foreplay. The restriction of space is emphasized as Caravaggio recounts the open spaces of the ocean or grasslands on his deathbed, yet the film includes not a single shot of the sky.

In Wittgenstein, Jarman further restricts the mise-en-scene space and uses nothing but a black background. Yet Wittgenstein does not experience the engulfing black as simply a form of claustrophobia. By using the black drape, Jarman was not only able to film the documentary on a minimal budget, but could also suggest that “the historicising attitude to biopic is totally irrelevant.” Jarman, who sought to make a philosophical film, said that “to redefine film, like language, needs a leap—in this case, the black drapes [defy] the narrative without junking it”. Time, space, and color are happening, juxtaposing an eternal and persistent void. Wittgenstein’s biographer Ray Monk lauded this approach in a review, saying that the black background embodies Wittgenstein’s “ahistorical, existential style of philosophizing and creates the entirely apposite impression that this is a story that is happening, not in any particular place, but rather in somebody’s—Wittgenstein’s—mind.” Eventually, on his deathbed, as Wittgenstein accepts his queer desires in an imperfect world, the child version of him rises out of the black drapes and flies up to the sky (a backdrop) on aeronautic wings. Wittgenstein leaves the alienating world that has been portrayed thus far in the film.

Jarmanesque props are also an important mise-en-scene element. Jarman references Leonardo da Vinci’s engineering drawings by giving Wittgenstein kite wings and having him hold lawn sprinklers in his hands. The sprinklers' jets of water resemble the spinning propellers of a plane. Jarman’s anachronistic choice of props was inspired by the props in Caravaggio’s paintings. In Penitent Magdelane, only the pearls and bottle of perfume indicate that the subject is Mary Magdalene. Her identity is otherwise unclear because the model is a prostitute dressed in 16th century clothing. Caravaggio’s mix of historical and contemporary objects suggests a connection between the historical subject and the viewer. Like the props in Caravaggio’s paintings, those in Jarman’s films suggest that history exists within the present and is embodied by contemporary models and objects. In one scene of Caravaggio, the aristocratic banker pompously fiddles with an electronic calculator that shows the timeless relationship between art and commerce. The vicious art critic attacks Caravaggio’s paintings and sexuality using a typewriter, perhaps referring to contemporary Tories that attacked Jarman personally in Sunday Times. The pope jeers at Caravaggio with a modern term “you little bugger” when he claims that art only helps the status quo. Through anachronistic props, Jarman shows the timelessness of artists’ tension with the establishment.

Jarman engages with Caravaggio and Wittgenstein’s theoretical ideas as well as personal dilemmas to show that they are not only brilliant but also troubled by their queer sexuality. Equipped with mise-en-scene elements such as lighting techniques, schematic colors and anachronistic props incorporated in his meticulously written script, Jarman directed nuanced films such as Wittegenstein and Caravaggio that explore many provocative themes during conservative eras. As an artist, Jarman feels responsible to show those details and nuances that cannot yet be fitted into a theoretically coherent framework, where the “attrition between private and public worlds” is felt strongest. Jarman used cinema “to express his beliefs, his dreams, his emotions, his ideologies, his needs. That is the difference between the artist and the technician who both make films.” Combining extraordinary vision, intellect and effort, he effectively conveyed his personal and theoretical readings of the two figures’ queer identities in Caravaggio and Wittgenstein.

Bibliography

Beristain, Gabriel. Caravaggio (DVD audio commentary). Dir. Derek Jarman. Cinevista, 1986. DVD. Zeitgeist Films. 2008.

Clark, James. "Jarman's Wittgenstein." Jim's Reviews. http://jclarkmedia.com/jarman/jarman10.html (accessed December 5, 2010).

Ellis, Jim. Derek Jarman's Angelic Conversations. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Fox, Sharon. A perceptual basis for the lighting of Caravaggio's faces. Journal of Vision. August 1, 2004 vol. 4 no. 8 article 215. <http://www.journalofvision.org/content/4/8/215.abstract>

Jarman, Derek. Caravaggio. Thames and Hudson, London, 1986. 44.

Jarman, Derek. Dancing Ledge. Quartet Books, London, 1984.

Jarman, Derek. "This is Not a Film of Ludwig Wittgenstein." In Wittgenstein: the Terry Eagleton script, the Derek Jarman film. London: British Film Institute, 1993. 63-67.

Jarman, Derek, and Roger Wollen. Derek Jarman: a portrait. London: Thames And Hudson, 1996.

Monk, Ray. ‘Between Earth and Ice: Derek Jarman’s Film of the life of Wittgenstein’. In The Times Literary Supplement, 19 March 1993.

Nash, Mark. 'Innocence and of Experience,' Afterimage 12, Autumn 1985. 30.

Pencak, William. “Caravaggio and the Italian Renaissance” and “Wittgenstein: The Grey Flame and the Early Twentieth Century.” In The films of Derek Jarman. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2002. 70-84, 108-119.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Remarks on Colour. Oxford: Blackwell, 1977.

Wymer, Rowland. Derek Jarman. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Michelangelo Caravaggio’s The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew.

Appendix 2: Wittgenstein, the da Vinci design, and sprinklers. Wittgenstein

Appendix 3: Caravaggio’s Penitent Magdelane

豆瓣Appendix 4:写着两部片儿的起因

最近又有新的电影paper要写 8-10p 随便什么topic都行

我苦思冥想数日 从伍迪艾伦到wes anderson,从青年文化想到记者类电影,都因为各种原因被我自己一一否决。(太平庸 太日常 被说烂了 我已经知道太多有偏见的,etc)(选research电影难度在于,又要喜欢研究对象,又不能太喜欢——否则你没办法置身于高处去评判!!比如wes anderson……)

昨天随意浏览豆瓣电影的时候看到以前打5星的《维特根斯坦因》 正好里面很多我没理解的概念 同时觉得很牛逼 于是come up with the rough thesis:When Jarman narrates Ludwig Wittgenstein's life in the film, how does is the director incorporating the philosopher’s ideas on language?

随后让季先生帮我借了N本关于维叔叔和他理论的书……爽~~

今天去找老师的时候 他听到我选择这部电影时就笑出来了

“我为什么笑啊,其实我应该为你高兴才对嘛,只不过我是太久以前看的了(刚出的时候老师就看了……),所以觉得又惊又喜!”持续表达自己的惊讶,“What a surprising choice!You have an interest in philosophy?” 他没想到我对哲学还有兴趣

我解释了一番thesis,老师又问我为什么想处这个的 我说 因为一直觉得哲人的思想与他们的真实生活之间的联系很微妙。老师质问,什么是‘真实’?我说,想法与生活态度毕竟还是两回事。 他说,嗯确实,随即开始自言自语“电影能体现出image's immediacy”什么的,我也顺手记下来了

建议:1 don't try to become a master on wittgenstein's ideas. 很多人花一辈子都没整明白

2 focus on the text itself, don't be too absorbed with w's thoughts

说不定要拿这个作为主体,与《蓝》、《Jubilee》的风格做一些联系(“Jubilee is a very accessible film。你对朋克文化感兴趣吗?里面有所涉及”“嗯,有的”)(我居然说得这么淡定)

他也非常喜欢Jarman,把他与queer vision联系起来,因为同性恋男导们其实都一种独特的表达方式,虽然往往与同性恋这个主题不是很相关

“You are such an unusual student!在我看来,你对抽象的想法这么感兴趣,你以后应该很喜欢电影理论的。可惜啊~你不在我下学期的queer vision课上~我们要讨论帕索里尼啊~以及他对天主教的各种奇怪见解”

“帕索里尼,是拍索多玛的对吧?”

“对”

“嗯。。确实会很有意思呢。话说你看戏剧作品《马拉/萨德》了吗?”

“没有!我本应该去看的!悔恨啊!我消息太闭塞了;以后一定要找到获取这些信息的渠道!”

总之跟电影老师每次谈话都很欢乐很活跃~~虽然我们两个人都有点shy~

对于大众来说为什么牛逼:

成本低,概念高。演员也都选得好

而导演Jarman也是很下功夫。当时几近失明的他,把维老他的人和他的思想都读透了。改写剧本时Jarman大胆想象,写成了这么一部轻松诙谐加自我调侃的同志哲人传记片。我就喜欢这种先锋的自我解读,而不是循规蹈矩走传统传记路线。

对于我个人来说为什么牛逼:

感情呈现的起乘转折的节奏把握得特别好。不乏感人的台词,尤其是结尾凯恩斯的那段独白比喻,听得心都融化了。

我和片中偏执地寻找『私人语言』维老有同感。时常在个人的孤独感中纠结与人交流时所遇到的困难。

他认为 解决这种孤独 尤其是哲人的孤独(brooding over its private experience) 的方式就是寻找公共语言

而完善这种语言的方式就是让所有人的逻辑体系都是理性的、一致的。

当有人对他做侮辱手势的时候,他开始意识到,人类的语言不可能完美。

他执着而天真 聪明而钻牛角尖 不爱都不行。

好吧其实是为了贴作业的,调研贾曼的两部电影

中心论点在第一段。。关于电影中的同志题材和场景设置

Derek Jarman’s Personal Narrative—Exploring Ludwig Wittgenstein and Michelangelo Caravaggio’s Brilliance and Queer Identities

As one of the best-known British queer directors, Derek Jarman produced several unique biopics of talented men tortured by their repressed homosexuality. Notably, Jarman started his career in feature film by working with Ken Russell, a director who reinvented the artist biopic by “introducing startling fantasy sequences and ostentatious camera movements.” Jarman continued Russell’s revolt against conventional realist representation of historical figures. Also using biopics as a form of documentation, Jarman has sought to reenact experience and thereby reconstruct affective relations. He identifies with brilliant queer men who are often too radical for their times. By portraying queer figures, Jarman interprets art and philosophy as well as repressed emotions and loneliness of queer men. Even during the conservative periods, Jarman’s nuanced films carried many provocative themes that were not only political but also highly personal. Caravaggio (1986) and Wittgenstein (1993) exemplify these aspects of Jarman’s individualistic, subjective approach. Jarman admits to strongly identifying with Wittgenstein: “I have much of Ludwig in me. Not in my work, but in my life.” Jarman has also stated in interviews that his artistic dilemmas are similar to those experienced by Caravaggio. This research paper attempts to capture the richness of Jarman's personal relationship with these two figures by discussing both films’ use of mise-en-scene and their thematic concern with queer identity.

Jarman engages with the lives of Wittgenstein and Caravaggio by referencing and paying homage to their work on a theoretical level. A painter and former set designer, Jarman emphasizes the use of mise-en-scene as substitute for literal narrative. In Jarman's films, staging and visual imagery are the most important qualities, while “narrative takes second place". While the lack of emphasis on logical narrative granted him more space to experiment, viewers with little knowledge of the characters are often confused. Jarman concentrates on constructing the plot around Caravaggio's paintings rather than his life and times. Critics have pointed out the absence of a clear narrative in Caravaggio. The characters and their relations to Caravaggio are unclear and sometimes misleading. Many supporting characters do not have presence in the plot that was fully distinct from their respective paintings. Yet Jarman believed he had to establish a unique perspective in order to capture Caravaggio’s dramatic “Hollywood template” life in a 90-minute film without resorting to clichés. Narrative ambiguity allows Jarman to “recreate many details of [his] life and, bridging the gap of centuries and cultures, to exchange a camera with a brush.” He interweaves the paintings with the plot with a painstakingly reworked script that involved 16 rewrites, as well as magnificent tableaux vivant production sets. Jarman focuses on Caravaggio’s emotions, sexuality, dreams and events surrounding the creation of his paintings, redefining the genre of the artist biopic. The paintings drive the narrative, and the consciousness depicted is not that of independently conceived characters but that of the artist himself, Jarman-Caravaggio.

As a lifelong painter, Jarman appreciates the narrative power of mise-en-scene and highlights it in the set designs for both films. Jarman is fascinated by Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro to create the illusion of depth. He praised Caravaggio for inventing cinematic light and the noir style shadowed backgrounds. Jarman pays homage to this technique through tightly controlled lighting effects. The tone and shade of the walls and skin color convey more about the scene than the script. In most scenes, Jarman meticulously replicates Caravaggio’s light sources, which usually come from the left and therefore elicits stronger responses from the viewers. Jarman attempts to show that the chiaroscuro is effective to capture intense emotions not only on canvas but also in film. He pays homage to Caravaggio by employing light and emphasizes the timelessness of classic art techniques.

While Jarman painted cinema like the artist Caravaggio, he also philosophized it, as expressed in the mise-en-scene of Wittgenstein. Jarman portrays Wittgenstein’s general estrangement from a painfully foreign world as a result of both his abstract philosophy and his difficulties accepting his sexuality. Jarman shows a world that appears absurd from Wittgenstein’s perspective: the highly stylized acting and flamboyant costumes of other characters contrast with Wittgenstein’s naturalistic acting and gray tweed jacket. Wittgenstein questions himself throughout the film: “How can I be a logician before I am a human being? The most important thing is to settle accounts with myself!” He travels across Europe, fighting in the Great War, teaching in a rural school, and escaping to Ireland or Norway to familiarize himself with the strange world, yet its meaning is still “problematic.” Wittgenstein, troubled by his sexuality, also wished to live an ethical life guided by strict logic. Yet this longing for perfection is disrupted by the messiness of life and the fickleness of passions.

Jarman places symbolic visuals in the biopic, which remind sophisticated audiences of “Wittgenstein’s epigrammatic style” of writing. Lady Ottoline paints Bertrand Russell on canvas as a red monochrome. When he wrote the script, Jarman also tried to understand Wittgenstein’s personal life by reading his books. Remarks on Colour provided him with cinematic context to relate to Wittgenstein’s ideas: “Remarks on Colour was a path for me back to the Tractatus [Logico-Philosophicus].” Furthermore, Jarman’s schematic use of color contrasts between the repression of private feelings and the expression of straightforward colors. "The black annihilates the decorative and concentrates so my characters shine in it like red dwarfs—and green giants. Yellow lines and blue stars”, Jarman references the schematic use of colors in Wittgenstein poetically. Jarman later wrote an entire book—Chroma— to show how colors are solely products of human interaction. In Wittgenstein’s words: “I think that it is worthless and of no use whatsoever for the understanding of painting to speak of the characteristics of the individual colours.” Through referencing Wittgenstein’s ideas on colors in the mise-en-scene as well as script text, Jarman pays homage to the philosopher. Jarman also successfully uses film medium to explore abstract theories and overcomes limitations of language.

Jarman engages with Wittgenstein and Caravaggio not only on a theoretical level but also reads into their personal struggles with homosexuality. Similar to abstract theories, Jarman’s Wittgenstein believed that homosexuality is an area that restricts language as a mode of expression. “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent,” Wittgenstein once wrote. In Jarman’s dialogue and cinematography, Wittgenstein's struggles to come to terms with his own philosophical ideas were inseparable from his attitude towards his sexuality. In one scene, three cyclists dressed in anachronistic jumpsuits abuse him with homophobic slurs and the insulting V-sign. Wittgenstein is flabbergasted and realizes there is no “logical structure” in the V-sign – the main argument of his first book. He plans to commit suicide but then rethinks his entire philosophy of language, completing his magnum opus Philosophical Investigations. Wittgenstein is confused by the logic of a curse, but Jarman sets the scene to suggest that Wittgenstein is confounded by homophobia. Jarman explains that Wittgenstein found a black hole in the logic, “for [the picture of Queer] there was no language.” Later, Bertrand Russell is infuriated after Wittgenstein convinces his student Johnny to work and drives him away from philosophy. Russell criticizes Wittgenstein for idealizing the common folk and “infecting too many young men” with his thought experiments. Jarman hints at Wittgenstein’s homosexual relationships with students through these double entendres. Wittgenstein's euphemisms, too, reflect his embarrassment concerning these relationships: He has “known” Johnny three times. Following this scene, Jarman places the mentally tormented Wittgenstein in a suspended cage. Wittgenstein ponders upon his relationships with his university and exclaims painfully: “Philosophy is the sickness of the mind. I mustn’t infect too many young men… living in a world where such a love is illegal and trying to live openly and honestly is a complete contradiction.” John Maynard Keynes, also clearly homosexual in the film, consoles Wittgenstein: “If you’d just allow yourself to be a little more sinful, you’d stand a chance of salvation.” Both Wittgenstein’s sexuality and philosophy alienates him from the real world. Jarman portrays a Wittgenstein who finds it difficult to distinguish between his philosophy and sexual passions.

Similarly, Jarman regards Caravaggio as the most homosexual of painters, based on his paintings rather than his biography. Jarman notes that Caravaggio paints his own face staring from the back of the crowd in The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew. He hypothesizes that “[Caravaggio] gazes wistfully at the hero slaying the saint. It is a look no one can understand unless he has stood till 5 a.m. in a gay bar hoping to be fucked by that hero. The gaze of the passive homosexual at the object of his desire, he waits to be chosen, he cannot make the choice”. Jarman reads Caravaggio's paintings for insights into his psychology and romantic relationships, and places these readings into his film. Caravaggio suffers creative drought while painting The Martyrdom. He encounters the attractive, masculine yet poor Ranuccio and selects him as a model. Ranuccio, the object of desire, inspires Caravaggio to finish the painting. Caravaggio showers him with gold coins in a suggestive fashion and also delivers one of the coins mouth to mouth. At the final stage, Caravaggio gazes intensely at Ranuccio still posed as the Martyr, forming a tableau vivant of the painting. His role as the artist desiring for Caravaggio and man yearning for St. Matthew in the painting is blurred. Caravaggio says in a voiceover, “I will seek him, whom my soul loves. I sought him, but found him not.” Jarman depicts Caravaggio as having romantic yet passive sentiments for the undesirable and shows this through ingenious mise-en-scene.

Elsewhere, Jarman portrays Caravaggio’s passivity as a product of the hypocrisy of the Roman Catholic establishment’s homophobia. He reads in the same painting “pernicious self-hatred [homosexuals] fostered among themselves… which is the key to Caravaggio’s life and destruction—it’s written all over the painting.” Jarman also identifies many of Caravaggio’s paintings as claustrophobic. Believing that there is a connection between Caravaggio’s style and his state of mind, Jarman films all of the scenes in studio with claustrophobic environments to suggest Caravaggio’s suffocation in a homophobic society. There is only one exterior scene in Caravaggio, in which Ranuccio and Lena are engaging in heterosexual foreplay. The restriction of space is emphasized as Caravaggio recounts the open spaces of the ocean or grasslands on his deathbed, yet the film includes not a single shot of the sky.

In Wittgenstein, Jarman further restricts the mise-en-scene space and uses nothing but a black background. Yet Wittgenstein does not experience the engulfing black as simply a form of claustrophobia. By using the black drape, Jarman was not only able to film the documentary on a minimal budget, but could also suggest that “the historicising attitude to biopic is totally irrelevant.” Jarman, who sought to make a philosophical film, said that “to redefine film, like language, needs a leap—in this case, the black drapes [defy] the narrative without junking it”. Time, space, and color are happening, juxtaposing an eternal and persistent void. Wittgenstein’s biographer Ray Monk lauded this approach in a review, saying that the black background embodies Wittgenstein’s “ahistorical, existential style of philosophizing and creates the entirely apposite impression that this is a story that is happening, not in any particular place, but rather in somebody’s—Wittgenstein’s—mind.” Eventually, on his deathbed, as Wittgenstein accepts his queer desires in an imperfect world, the child version of him rises out of the black drapes and flies up to the sky (a backdrop) on aeronautic wings. Wittgenstein leaves the alienating world that has been portrayed thus far in the film.

Jarmanesque props are also an important mise-en-scene element. Jarman references Leonardo da Vinci’s engineering drawings by giving Wittgenstein kite wings and having him hold lawn sprinklers in his hands. The sprinklers' jets of water resemble the spinning propellers of a plane. Jarman’s anachronistic choice of props was inspired by the props in Caravaggio’s paintings. In Penitent Magdelane, only the pearls and bottle of perfume indicate that the subject is Mary Magdalene. Her identity is otherwise unclear because the model is a prostitute dressed in 16th century clothing. Caravaggio’s mix of historical and contemporary objects suggests a connection between the historical subject and the viewer. Like the props in Caravaggio’s paintings, those in Jarman’s films suggest that history exists within the present and is embodied by contemporary models and objects. In one scene of Caravaggio, the aristocratic banker pompously fiddles with an electronic calculator that shows the timeless relationship between art and commerce. The vicious art critic attacks Caravaggio’s paintings and sexuality using a typewriter, perhaps referring to contemporary Tories that attacked Jarman personally in Sunday Times. The pope jeers at Caravaggio with a modern term “you little bugger” when he claims that art only helps the status quo. Through anachronistic props, Jarman shows the timelessness of artists’ tension with the establishment.

Jarman engages with Caravaggio and Wittgenstein’s theoretical ideas as well as personal dilemmas to show that they are not only brilliant but also troubled by their queer sexuality. Equipped with mise-en-scene elements such as lighting techniques, schematic colors and anachronistic props incorporated in his meticulously written script, Jarman directed nuanced films such as Wittegenstein and Caravaggio that explore many provocative themes during conservative eras. As an artist, Jarman feels responsible to show those details and nuances that cannot yet be fitted into a theoretically coherent framework, where the “attrition between private and public worlds” is felt strongest. Jarman used cinema “to express his beliefs, his dreams, his emotions, his ideologies, his needs. That is the difference between the artist and the technician who both make films.” Combining extraordinary vision, intellect and effort, he effectively conveyed his personal and theoretical readings of the two figures’ queer identities in Caravaggio and Wittgenstein.

Bibliography

Beristain, Gabriel. Caravaggio (DVD audio commentary). Dir. Derek Jarman. Cinevista, 1986. DVD. Zeitgeist Films. 2008.

Clark, James. "Jarman's Wittgenstein." Jim's Reviews. http://jclarkmedia.com/jarman/jarman10.html (accessed December 5, 2010).

Ellis, Jim. Derek Jarman's Angelic Conversations. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Fox, Sharon. A perceptual basis for the lighting of Caravaggio's faces. Journal of Vision. August 1, 2004 vol. 4 no. 8 article 215. <http://www.journalofvision.org/content/4/8/215.abstract>

Jarman, Derek. Caravaggio. Thames and Hudson, London, 1986. 44.

Jarman, Derek. Dancing Ledge. Quartet Books, London, 1984.

Jarman, Derek. "This is Not a Film of Ludwig Wittgenstein." In Wittgenstein: the Terry Eagleton script, the Derek Jarman film. London: British Film Institute, 1993. 63-67.

Jarman, Derek, and Roger Wollen. Derek Jarman: a portrait. London: Thames And Hudson, 1996.

Monk, Ray. ‘Between Earth and Ice: Derek Jarman’s Film of the life of Wittgenstein’. In The Times Literary Supplement, 19 March 1993.

Nash, Mark. 'Innocence and of Experience,' Afterimage 12, Autumn 1985. 30.

Pencak, William. “Caravaggio and the Italian Renaissance” and “Wittgenstein: The Grey Flame and the Early Twentieth Century.” In The films of Derek Jarman. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2002. 70-84, 108-119.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Remarks on Colour. Oxford: Blackwell, 1977.

Wymer, Rowland. Derek Jarman. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Michelangelo Caravaggio’s The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew.

Appendix 2: Wittgenstein, the da Vinci design, and sprinklers. Wittgenstein

Appendix 3: Caravaggio’s Penitent Magdelane

豆瓣Appendix 4:写着两部片儿的起因

最近又有新的电影paper要写 8-10p 随便什么topic都行

我苦思冥想数日 从伍迪艾伦到wes anderson,从青年文化想到记者类电影,都因为各种原因被我自己一一否决。(太平庸 太日常 被说烂了 我已经知道太多有偏见的,etc)(选research电影难度在于,又要喜欢研究对象,又不能太喜欢——否则你没办法置身于高处去评判!!比如wes anderson……)

昨天随意浏览豆瓣电影的时候看到以前打5星的《维特根斯坦因》 正好里面很多我没理解的概念 同时觉得很牛逼 于是come up with the rough thesis:When Jarman narrates Ludwig Wittgenstein's life in the film, how does is the director incorporating the philosopher’s ideas on language?

随后让季先生帮我借了N本关于维叔叔和他理论的书……爽~~

今天去找老师的时候 他听到我选择这部电影时就笑出来了

“我为什么笑啊,其实我应该为你高兴才对嘛,只不过我是太久以前看的了(刚出的时候老师就看了……),所以觉得又惊又喜!”持续表达自己的惊讶,“What a surprising choice!You have an interest in philosophy?” 他没想到我对哲学还有兴趣

我解释了一番thesis,老师又问我为什么想处这个的 我说 因为一直觉得哲人的思想与他们的真实生活之间的联系很微妙。老师质问,什么是‘真实’?我说,想法与生活态度毕竟还是两回事。 他说,嗯确实,随即开始自言自语“电影能体现出image's immediacy”什么的,我也顺手记下来了

建议:1 don't try to become a master on wittgenstein's ideas. 很多人花一辈子都没整明白

2 focus on the text itself, don't be too absorbed with w's thoughts

说不定要拿这个作为主体,与《蓝》、《Jubilee》的风格做一些联系(“Jubilee is a very accessible film。你对朋克文化感兴趣吗?里面有所涉及”“嗯,有的”)(我居然说得这么淡定)

他也非常喜欢Jarman,把他与queer vision联系起来,因为同性恋男导们其实都一种独特的表达方式,虽然往往与同性恋这个主题不是很相关

“You are such an unusual student!在我看来,你对抽象的想法这么感兴趣,你以后应该很喜欢电影理论的。可惜啊~你不在我下学期的queer vision课上~我们要讨论帕索里尼啊~以及他对天主教的各种奇怪见解”

“帕索里尼,是拍索多玛的对吧?”

“对”

“嗯。。确实会很有意思呢。话说你看戏剧作品《马拉/萨德》了吗?”

“没有!我本应该去看的!悔恨啊!我消息太闭塞了;以后一定要找到获取这些信息的渠道!”

总之跟电影老师每次谈话都很欢乐很活跃~~虽然我们两个人都有点shy~

3 ) 永远的维特根斯坦

就像维特根斯坦自己说的:“电影就像一个冲淋浴,把讲义冲走。”他喜欢看电影,讨厌研讨会。

我也可以说:“看一部歌剧形式的电影《维特根斯坦》比看他的著作有趣的多!”电影通常比较直观易懂。(另有一例是关于经济学家纳什的电影——《美丽心灵》,电影充满悬疑,帅哥美女,还很温情,但他博弈论应该不是那么好理解的。)

据说维特根斯坦是哲学界的爱因斯坦,没有几个人能理解他的思想,他却总被许多人津津乐道。他出生富裕,是罗素的学生,在战壕里写哲学著作,他是哲学家,同时也是工程师,他还是个gay。

他有个“洛克斯菲尔德”般富裕的家庭,爸爸是欧洲钢铁工业的巨头,妈妈是银行家的女儿。他的家教历史老师与希特勒是同一位。也许是某些“家族基因”在作怪(我猜的),他的两个同性恋哥哥都死于自杀,还有一个哥哥自愿参加战争失去了一只右手,成了独臂钢琴家,写过一本《左手钢琴协奏曲》。

据说维特根斯坦曾问一位老师,“我笨吗?不笨可以学哲学,笨则可以去当飞行员。”他师从罗素在剑桥学哲学,但他讨厌剑桥,称其为“吵吵闹闹的妓院”。于是一个人住在挪威一个小村庄的小木屋里,还声称“寂寞也是一种福气”。

他还去过乡下当小学教师。有时候他会发挥他工程师的才能,修好一些机械设备,令村民们惊叹不已。聪明的学生经常能感受到他温暖的目光,但他也会将头脑笨的学生打成重伤送进医院。他的脾气很暴躁,即使在剑桥和其他著名学者交流,没等对方说上几句,他就叫了起来:“哦,不,不。不是那样的……”,说上近半个小时,最后握着对方的手说:“我们刚才的谈话很有趣,谢谢。”然后转身离开。

回到剑桥,他受不了研讨,学生说开完会,就去看电影,他才答应。他喜欢西部片和音乐剧,通常坐在最前排,让自己淹没在电影的音像中。

他总是劝他的学生去从事体力劳动,他自己也极其想去苏联做个体力劳动者。当周围的学生不理解他甚至嘲笑他的怪异的时候,他怒气冲冲的说要去自杀。不过也有喜欢他的学生说:“他如上帝般英俊、纯洁,超凡脱俗。”

他是个gay,很多时候都陷于道德上的自责,虽然别人劝慰他说:“世界上没有什么比得到满足的身体更温暖了。”可他事后依旧不安、羞愧,反省和自责。

他死于生理上的疾病,死的时候,他说了一句原创的名言:“告诉他们,我度过了美好的一生!”他也有遗憾,他想写一本完全由笑话组成的哲学书,可他流下了眼泪:“悲哀的是我毫无幽默感。”

————————————————————————

第一次接触维特根斯坦,是在一次现代西方哲学课上,他的分析哲学还有语言学让人昏头转向,极其难理解。印象深刻的是,上课的老师把维的著作《逻辑哲学论》拿给班上的同学传阅,用罗素的话说“书太短,非常难懂,但很好。”那本近乎于用“数学”的方式写的书,让我们惊叹不已。

其次是上课的老师给我们看了维给他姐姐设计的房子的照片,简洁、净穆。叹为观止!

我也可以说:“看一部歌剧形式的电影《维特根斯坦》比看他的著作有趣的多!”电影通常比较直观易懂。(另有一例是关于经济学家纳什的电影——《美丽心灵》,电影充满悬疑,帅哥美女,还很温情,但他博弈论应该不是那么好理解的。)

据说维特根斯坦是哲学界的爱因斯坦,没有几个人能理解他的思想,他却总被许多人津津乐道。他出生富裕,是罗素的学生,在战壕里写哲学著作,他是哲学家,同时也是工程师,他还是个gay。

他有个“洛克斯菲尔德”般富裕的家庭,爸爸是欧洲钢铁工业的巨头,妈妈是银行家的女儿。他的家教历史老师与希特勒是同一位。也许是某些“家族基因”在作怪(我猜的),他的两个同性恋哥哥都死于自杀,还有一个哥哥自愿参加战争失去了一只右手,成了独臂钢琴家,写过一本《左手钢琴协奏曲》。

据说维特根斯坦曾问一位老师,“我笨吗?不笨可以学哲学,笨则可以去当飞行员。”他师从罗素在剑桥学哲学,但他讨厌剑桥,称其为“吵吵闹闹的妓院”。于是一个人住在挪威一个小村庄的小木屋里,还声称“寂寞也是一种福气”。

他还去过乡下当小学教师。有时候他会发挥他工程师的才能,修好一些机械设备,令村民们惊叹不已。聪明的学生经常能感受到他温暖的目光,但他也会将头脑笨的学生打成重伤送进医院。他的脾气很暴躁,即使在剑桥和其他著名学者交流,没等对方说上几句,他就叫了起来:“哦,不,不。不是那样的……”,说上近半个小时,最后握着对方的手说:“我们刚才的谈话很有趣,谢谢。”然后转身离开。

回到剑桥,他受不了研讨,学生说开完会,就去看电影,他才答应。他喜欢西部片和音乐剧,通常坐在最前排,让自己淹没在电影的音像中。

他总是劝他的学生去从事体力劳动,他自己也极其想去苏联做个体力劳动者。当周围的学生不理解他甚至嘲笑他的怪异的时候,他怒气冲冲的说要去自杀。不过也有喜欢他的学生说:“他如上帝般英俊、纯洁,超凡脱俗。”

他是个gay,很多时候都陷于道德上的自责,虽然别人劝慰他说:“世界上没有什么比得到满足的身体更温暖了。”可他事后依旧不安、羞愧,反省和自责。

他死于生理上的疾病,死的时候,他说了一句原创的名言:“告诉他们,我度过了美好的一生!”他也有遗憾,他想写一本完全由笑话组成的哲学书,可他流下了眼泪:“悲哀的是我毫无幽默感。”

————————————————————————

第一次接触维特根斯坦,是在一次现代西方哲学课上,他的分析哲学还有语言学让人昏头转向,极其难理解。印象深刻的是,上课的老师把维的著作《逻辑哲学论》拿给班上的同学传阅,用罗素的话说“书太短,非常难懂,但很好。”那本近乎于用“数学”的方式写的书,让我们惊叹不已。

其次是上课的老师给我们看了维给他姐姐设计的房子的照片,简洁、净穆。叹为观止!

4 ) 不食人家烟火的“神人们”之间的情景爆笑喜剧

舞台背景和道具很简约的爆笑情景话剧,但是看似又没有舞台,真人版拼接的人物情景模拟效果加上精选的台词,喜剧效果十分浓厚,当然要在对维特根斯坦的故事有一定的背景知识的情况下才能感受到。此片导演把艰深的话题轻松简约而又相对通俗的在展现在观众面前,对于舞台虚拟消失化的处理,以及简单道具的应用很到位,真是一次伟大的创作。看来庄重贵族绅士的英国人有着一流的讲故事的能力,而这样的优点也体现在今天的BBC的纪录片里面。

里面有个十分可爱且帅气的小正太扮演的童年版的维特根斯坦,会时不时的以“画外音”的方式出现在故事的叙述过程中,有诙谐且点醒我们的效果。

维特根斯坦,在这个严肃的世界里,和谢耳朵一样可爱,但比谢耳朵更偏执却十足理性更具有真实感,当然很重要的原因是因为前者就是真实存在过的人吧。一个在思想上歇斯底里的凡人,一个竭力证明自己的存在的人,证明自己为何存在的人?而这个问题,是大部分人通过涌入人流的方式而终生不作考虑。直到将要逝去,他才对这个问题真正感到释然,我们之外没有疑惑,安心去吧。

只有天才才能容得下天才,傻子从来是看不起天才或者只知道膜拜天才。

里面有个十分可爱且帅气的小正太扮演的童年版的维特根斯坦,会时不时的以“画外音”的方式出现在故事的叙述过程中,有诙谐且点醒我们的效果。

维特根斯坦,在这个严肃的世界里,和谢耳朵一样可爱,但比谢耳朵更偏执却十足理性更具有真实感,当然很重要的原因是因为前者就是真实存在过的人吧。一个在思想上歇斯底里的凡人,一个竭力证明自己的存在的人,证明自己为何存在的人?而这个问题,是大部分人通过涌入人流的方式而终生不作考虑。直到将要逝去,他才对这个问题真正感到释然,我们之外没有疑惑,安心去吧。

只有天才才能容得下天才,傻子从来是看不起天才或者只知道膜拜天才。

5 ) 《维特根斯坦》德吕克·贾曼

在这部影片中贾曼利用舞台和电影的结合的方式,一种怪诞的戏剧氛围描述了著名分析哲学家、逻辑学家、语言学家维特根斯坦的一生和他的哲学观点。影片前半段简要叙述了维特根斯坦早期充满戏剧性的个人经历,而在维特根斯坦重返剑桥之后,电影主要截取了维特根斯坦前后哲学观点转换时期的生活为主要叙述事件,结合他同性倾向和卓然不群的性格,体现了他在现实之中不断追求形而上的理想的孤傲精神。维特根斯坦在早期《逻辑哲学论》中讲世界结构与命题结构归结于一种具有相同逻辑结构的图式,从而揭示人们通过语言命题认识世界的方式。之后,维特根斯坦又根据本体论的角度指出了语言的自我界限以及人的意志和对世界体验的神秘主义特性。然而,在对哲学问题进行了痛苦思考之后,维特根斯坦放弃了曾经“语言是世界图式”的主张,而提出了日常语言分析哲学的“语言-游戏”理论,并要求对语言的分析必须将语言置入特定的用法环境才能显示它的特定含义。联系日常语言分析,维特根斯坦通过纠正对语言的误解来消除哲学问题,他认为哲学困境的产生在于人们混淆的使用了不同性质的语言而造成的逻辑和意义上的误解。导演德吕克·贾曼在1993年拍摄了《维特根斯坦》和《蓝》,并随后死于艾滋病。

6 ) 哲学家电影【维特根斯坦】

这是一部现代风格的戏剧,介绍了生于维也纳,在剑桥读书的哲学家Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951)的生平及思想。他的主要兴趣在于研究语言的本质与极限。 电影使用最简单的黑色背景,所有的投资都用在服装、演员以及灯光上,构图就像黑暗的启蒙主义绘画。Wittgenstein以一个小男孩的形象出现,他的少年时代很压抑,银幕上他的家人都身穿罗马人的宽外袍。一系列的小场景描述了他从小时候,到第一次世界大战,再到最终在剑桥当教授和Bertrand Russell以及John Maynard Keynes合作的生平。 导演Derek Jarman使用了一些戏剧小品,还有富于想象力的小花招,比如出现了火星侏儒,来表现Wittgenstein的贵族举止,犹太背景,以及同性恋倾向。

哲思的趣味 能把妓院和剑桥画等号的 也只有他了吧

传记的剧情化与哲学主张的复现构成某种哲学影像化的方式;舞台剧的布景陈设和台词,与其说遵循戏剧传统倒不如说是对电影形式实验性地创新;恐怕只有同性恋导演才能将色彩运用得如此骚气波普;逝世一段太美了,“但是他的心中某处还是迷恋着冰原”。

(模糊)谨记是小概率事件,剑桥无法集中精力,不幸圣人幸福的弟,教师工作就是骗人,让自己不断往高处,在还来得及的时候,把清澈的水弄浑浊,语言误解的副产品,陈述众所周知事实,语言就是世界极限,没有经验的劳动者,朱威有点不劳而获,没感到自己优越感,去享乐虔诚新教徒,维特根斯坦+民哲

过度jarman风了

THIS IS A VERY PLEASANT PINEAPPLE.

现代风格戏剧,撷取维根斯坦一生中的若干片段,刻画了一个同性恋者,一个直觉、情绪化、骄傲的天才思想家形象。简单的黑色背景,小成本制作,构图如启蒙主义画作。维根斯坦以男孩形象出现,近景对镜头讲述他的生平和思想,伴有戏剧小品、火星侏儒等小花招。当然想深入了解这部电影还需首先了解人物

没看明白

对哲学无感

不错!喜欢这个叙事方式,让我想起Orlando,Tilda的文艺片大抵相近阿,是不是因为演了太多Jarman的电影- -

各种不懂 各种美

很实验,很具有深度和冲击力。

简单了点。另外,突然觉得,当维特根斯坦觉得哲学是一种病(因而否认了哲学的重要性)的时候,他却认同了日常生活、性爱、伦理、审美、宗教等等的价值。因此,该干嘛应该继续干嘛,别因为维族人说哲学没价值就觉得活着没意思。维族人的哲学甚至跟哲学生的哲学都或许不是一个意思~

有一个年轻人,想把全世界都总结在一个理论里。头脑非常聪明的他终于实现了这个梦想。完成工作后他回望自己的成果:真是非常漂亮,一个没有不完美不正确的世界,闪闪发光的冰原延伸到地平线。年轻人决定要探索自己的世界。刚刚迈出步子的他就仰倒在了地上,忘记了冰是纯洁无瑕的,没有任何污点,也没有摩擦,所以无法行走。年轻人坐在那里哭了起来。但是随着年龄增长他渐渐明白了,粗糙并不是缺点,正是粗糙使这个世界活动起来。他想跑起来,他想跳舞。散布在地面上的语言和事物是变形了的、污秽的、模棱两可的。聪明的老人领悟到这是理所当然的,但是他的心中某处还是迷恋着冰原,在那里一切都是辉煌纯粹的。虽然他渐渐喜欢上了粗糙的地面的观点,但是他却住不了。于是他就徘徊在地面和冰原之间,在哪一边都住得不安稳。这就是他悲哀的根源。

这就是维特根斯坦的危险之所在,他的神秘主义总是把人们导向非理性,而哲学家们却总想把他读作理性主义者。

这种电影没法打分

维特根斯坦的“沉默”“反哲学”实是基于哲学本源的探讨与对不可知性的宗教式敬畏。不断拒绝“自我认同”的维特根斯坦类似克尔凯郭尔的“三重阶段”。贾曼依旧保持造型艺术但比起《卡拉瓦乔》而言多了几分戏谑与黑色幽默。难道这正是维特根斯坦临终前想要用笑话书写的哲学著作?还是导演的遗书?

竟然真的把哲学拍成了图像。

用象征主义拍语言哲学的贾曼实验,天才和疯子只隔一线。维特根斯坦8岁时就开始思考死亡,他的人生如同繁复的迷宫,而把犹太人、同性恋、维也纳、剑桥这些身份碎片糅合在一起,也只能还原历史的一个断面。

Fascinating as his ideas.

我是来看Tilda Swinton的。电影让人相信这位哲学家就是长这样子,然后就是各种看不懂。