更新时间:2024-04-13 01:42

详细剧情

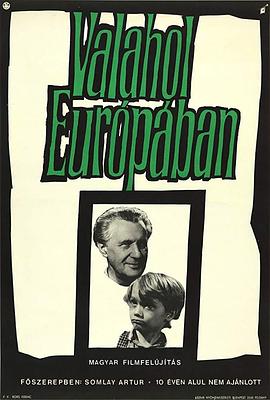

Somewhere in the remote region, the war ends. In the midst of ruined cities and houses in the streets, in rural hamlets, everywhere where people still live, are children who have lost their homes and parents. Abandoned, hungry, and in rags, defenseless and humiliated, they wander through the world. Hunger drives them. Little streams of orphans merge into a river which rushes forward and submerges everything in its path. The children do not know any feeling; they know only the world of their enemies. They fight, steal, struggle for a mouthful of food, and violence is merely a means to get it. A gang led by Cahoun finds a refuge in an abandoned castle and encounters an old composer who has voluntarily retired into solitude from a world of hatred, treason, and crime. How can they find a common ground, how can they become mutual friends? The castle becomes their hiding place but possibly it will also be their first home which they may organize and must defend. But even for this, the price will be very high. To this simple story, the journalist, writer, poet, scriptwriter, movie director, and film theoretician Béla Balázs applied many years of experience. He and the director Géza Radványi created a work which opened a new postwar chapter in Hungarian film. Surprisingly, this film has not lost any of its impact over the years, especially on a profound philosophical level. That is to say, it is not merely a movie about war; it is not important in what location and in what period of time it takes place. It is a story outside of time about the joyless fate of children who pay dearly for the cruel war games of adults. At the time it was premiered, the movie was enthusiastically received by the critics. The main roles were taken by streetwise boys of a children's group who created their roles improvisationally in close contact with a few professional actors, and in the children's acting their own fresh experience of war's turmoil appears to be reflected. At the same time, their performance fits admirably into the mosaic of a very complex movie language. Balázs's influence revealed itself, above all, in the introductory sequences: an air raid on an amusement park, seen in a montage of dramatic situations evoking the last spasms of war, where, undoubtedly, we discern the influence of classical Soviet cinematography. Shooting, the boy's escape, the locomotive's wheels, the shadows of soldiers with submachine guns, the sound of a whistle—the images are linked together in abrupt sequences in which varying shots and expressive sharp sounds are emphasized. A perfectly planned screenplay avoided all elements of sentimentality, time-worn stereotypes of wronged children, romanticism and cheap simplification. The authors succeeded in bridging the perilous dramatic abyss of the metamorphosis of a children's community. Their telling of the story (the scene of pillaging, the assault on the castle, etc) independently introduced some neorealist elements which, at that time, were being propagated in Italy by De Sica, Rossellini, and other film artists. The rebukes of contemporary critics, who called attention to "formalism for its own sake" have been forgotten. The masterly art of cameraman Barnabás Hegyi gives vitality to the poetic images. His angle shots of the children, his composition of scenes in the castle interior, are a living document of the times, and underline the atmosphere and the characters of the protagonists. The success of the picture was also enhanced by the musical art of composer Dénes Buday who, in tense situations, inserted the theme of the Marseilaise into the movie's structure, as a motive of community unification, as an expression of friendship and the possibility of understanding. Valahol Europaban is the first significant postwar Hungarian film. It originated in a relaxed atmosphere, replete with joy and euphoria, and it includes these elements in order to demonstrate the strength of humanism, tolerance, and friendship. It represents a general condemnation of war anywhere in the world, in any form.

长篇影评

1 ) 经典

经典的儿童电影。在匈牙利影史排名落后于《我的二十世纪》、《米菲斯特》、《辛巴德》真是亏待了这部杰作。该片完全不逊于意大利新现实主义作品。

不少镜头、灯光和阴影打的很让人惊艳,就是结尾处俗套了点

8。战末匈牙利某村某群小孩

被遗忘的电影 被遗忘的人

2018312 一星平庸

马赛曲。这是全世界最流行的国歌吧。

不知道匈牙利人为何如此喜欢《马赛曲》。被俘老头一坐下弹的就是《马赛曲》,然后背景音乐、口哨、口琴到处是它的片段。扬索的《红军与白军》结尾,红军齐唱的也是《马赛曲》,而不是《国际歌》

到马赛曲的高潮都是很好的,光影的运用,暴力时拍摄墙上挂着的肖像、雕塑的微笑。但这之后就是个平庸的革命故事了。重复运用马赛曲反而折射出了这个故事的单薄。虽然这是1948的匈牙利电影,不能说这个故事“俗套”,但确实很单薄。

某个地方可以做普遍地方的折射角度。

描述一群孩子在二战接近尾声时的遭遇百度云

练习偷窃,抢劫,欺骗,练习暴力,练习活着,在残暴的世界只有“恶童”。大人的自由要加上多少的形容词,而对孩子只要一个就够了:游戏。镜头可喜

最沉重的囚牢就是苦难。

看到某资源博发才想起以前看过这部...

故事狗血,形式精彩,Propaganda+Italian Neorealism。

相似于禁忌的遊戲,只是相對直接一點,並且結局沒有那麼絕望。

说教,脸谱化,该背黑锅的背黑锅,该挨枪的挨枪。

动乱时期的孩子,很容易走上歧路,何况一群穷孩子。幸运的话,碰上一个优秀的导师。

感谢字幕人

战争孤儿流浪记,儿童视角反思战争罪行,指挥家的出现让一群流浪儿通过音乐实现了启蒙和成长。

他们的未来自由吗。