更新时间:2024-04-13 01:40

详细剧情

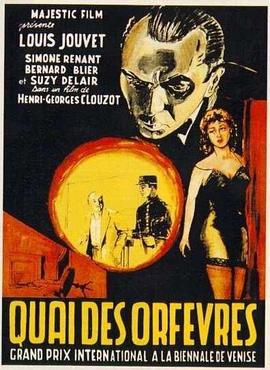

故事说的是一对在杂耍剧院表演的贫穷夫妇,男的生性嫉妒;女的却又偏怀野心,经常梦想着一天能出人头地。一次有位富商邀请该女子去拍电影,实质上想暗中勾引她;丈夫得知后妒火顿生,便痛斥富商的淫亵,扬言要杀掉富商解气。谁知就在他尚未动手之际,富商却已遭人暗杀,丈夫由此惹上官司。这对落难鸳鸯又该如何脱身?

长篇影评

1 ) 关于本片观影(之前)的三言两语

时间:2008年9月23日18:30

地点:cinematheque quebecoise魁北克电影馆

事件:olivier barrot主持观影会

今晚两大卖点:

1,能亲睹这部法国经典“国片”的35mm胶片版;

2,法国著名电视书评人和影史家olivier barrot在正片放映前的60分钟现场讲评。

故又是全场爆满。

barrot不多谈电影本身的内容,反而从影片诞生时期的大气候着眼-

二战后2-3年间,法国国内物资极度贫乏;

第三次世界大战的可能性?

冷战开场;

法国大量引进好莱坞电影制作;

……

再谈HG克鲁佐如何在对原作记忆模糊的情况下将其改编为剧本等等。

结束语来自片中警探安东万那句著名的“我这样的家伙对女人是没机会的!”(Vous êtes un type dans mon genre, vous n'avez pas de chance avec les femmes !)

地点:cinematheque quebecoise魁北克电影馆

事件:olivier barrot主持观影会

今晚两大卖点:

1,能亲睹这部法国经典“国片”的35mm胶片版;

2,法国著名电视书评人和影史家olivier barrot在正片放映前的60分钟现场讲评。

故又是全场爆满。

barrot不多谈电影本身的内容,反而从影片诞生时期的大气候着眼-

二战后2-3年间,法国国内物资极度贫乏;

第三次世界大战的可能性?

冷战开场;

法国大量引进好莱坞电影制作;

……

再谈HG克鲁佐如何在对原作记忆模糊的情况下将其改编为剧本等等。

结束语来自片中警探安东万那句著名的“我这样的家伙对女人是没机会的!”(Vous êtes un type dans mon genre, vous n'avez pas de chance avec les femmes !)

2 ) 很黑色,也很娱乐

对我个人来说,它是一部别开生面的犯罪电影。影片在绝大多数时间里,居然是处在一种欢乐,幽默的气氛之中。(这种气氛与影片的黑色主基调其实是格格不入的,这让作为观众的我觉得导演似乎有些“叙事混乱”了)。

有趣的是,导演Henri-Georges Clouzot自己说他是以记录片的手法拍摄了这部电影,可能在他看来这个世界的本色就是混乱的,不可理喻的,但是我们却应该以积极,快乐的心态来面对这一切。(但其中也应该有另一方面原因,那就是照顾到影片的娱乐性与商业性)。

直到影片临到结束之前,气氛才陡然变得紧张与严肃起来。(以男主人公试图自杀的情节开始时为分水岭)

导演最终告诉我们,女主角居然不是杀人凶手,真正的杀人其实是一个黑帮份子。

一个主流化的,大团圆的结局?!

但请注意,事实并没有这么简单,警长揭发出谋杀案真正凶手的主要动因是因为他喜欢那名女同性恋者,而并不是为了所谓的公平与正义。

典型的法国式的黑色与暧昧!

有趣的是,导演Henri-Georges Clouzot自己说他是以记录片的手法拍摄了这部电影,可能在他看来这个世界的本色就是混乱的,不可理喻的,但是我们却应该以积极,快乐的心态来面对这一切。(但其中也应该有另一方面原因,那就是照顾到影片的娱乐性与商业性)。

直到影片临到结束之前,气氛才陡然变得紧张与严肃起来。(以男主人公试图自杀的情节开始时为分水岭)

导演最终告诉我们,女主角居然不是杀人凶手,真正的杀人其实是一个黑帮份子。

一个主流化的,大团圆的结局?!

但请注意,事实并没有这么简单,警长揭发出谋杀案真正凶手的主要动因是因为他喜欢那名女同性恋者,而并不是为了所谓的公平与正义。

典型的法国式的黑色与暧昧!

3 ) On the Heights of Despair

On the Heights of Despair

By Aimée

For his collaboration with the Continental during the Occupation when he made Le Corbeau (1943), Henri-Georges Clouzot was barred from filmmaking for four years. After the sanctions were lifted, Clouzot returned with a dazzling piece of comedie humaine: Quai des Orfèvres (1947). The film features an ambitious chanteuse Jenny and her hapless pianist-accompanist husband Maurice who find themselves involved in the murder of a lecherous admirer of Jenny’s. Eventually, a minor character Paolo is found guilty of the crime. After Maurice is released from prison to return home, the couple celebrates a happy Christmas together. If one takes Quai des Orfèvres at face value, the film can be read as a conventional Christmas tale with an unsurprising ending. However, a closer look at the film’s characterization and aesthetic choices suggests otherwise. The multi-layered, self-reflective film essentially resists the sentimental optimism that its Hollywood counterparts persist to promote and calls into question the fetishism of glamour and style. Clouzot further directs the spectator’s gaze onto a disenchanting world of desires and despair, and places the cinematic apparatus that produces the desires under examination.

The film presents the spectator with a study of man and women, of their desires and despair. The arriviste torch singer Jenny is constructed as the center of desires. The first time the spectator encounters Jenny is through Maurice’s surveillant yet lustful gaze. In a point of view shot, the viewer discovers Jenny sitting confidently on the table with her legs half-covered by a luxurious fur coat while she is practicing her Belle Époque-reviving risqué songs on the side of a flirtatious music producer. Maurice desires Jenny but is often overshadowed by her other more resourceful admirers. Imbued with jealousy and despair, Maurice eventually resorts to his murderous impulse. In the following shots bridged by Jenny’s alluring delivery of the voluptuous song “Avec son tra-la-la”, the viewer soon discovers another admirer Dora, who is smoking and fixatedly gazes at Jenny. It later becomes explicit that Dora has feelings for Jenny but her love is without hope and will never be requited. In the subsequent shot from Dora’s point of view, the viewer finds Jenny practicing the song in a three-way mirror and stares at the fragmented, multiplied images of herself, as if she desires her own images. The accumulation of desires finally reaches its peak as Jenny performs on the stage, exciting her audience with bubbly lines and apt body dynamics. Jenny actively seeks others’ gazes and derives pleasure in being looked at, for she believes her sexual energy and desirability will help her secure fame and money. But eventually her desire for becoming a movie star is unrealized. In one way or another, Jenny, Maurice, and Dora all become involved in the murder of Brignon because of their desires for something, whether it is love, sex, fame, or capital. Clouzot’s camera articulates the play of desires. As the film progresses, the desires create immense troubles for his characters.

It may seem that Clouzot is recycling the most widely used tropes and unimaginatively uses cinematic devices that belong to the inventory of classical Hollywood cinema from the early-to-mid century. However, while sharing some basis in narrative and aesthetics, Quai des Orfèvres differs from its Hollywood counterparts at a fundamental level for its subversive practice that aims to negate pleasure and casts ridicule on the fetishism itself. Such subversion is evidenced by Clouzot’s malicious choice of casting Simone Renant as a lesbian in plaid knit sweater, thick wool trousers, and other airtight unattractive plain clothes – a character that resists fetishistic gazes. Apart from two close-up shots that glamorize Renant’s face, Clouzot’s camera does not give the spectator access to fetishizing the body of the “highly elegant, blond and pink apparition, who at the time was regarded as the most beautiful actress in Paris” . Moreover, Renant with her eye-catching blondness and dress in American style functions as a stand-in for Hollywood fetish stars. However, by denying access to her body and glamor, Clouzot inverts her role and uses her images precisely to resist “the very objectification she appears to embody.” Another example is Jenny’s photograph that Dora takes for an American magazine. In the well-lit room where everything radiates glamour, Jenny fakes to cover her chest with her hand and strikes a mawkish lover-girl pose when Dora presses the shutter. The saccharine image is more idiotic than attractive. By framing Jenny, the supposedly most attractive and alluring female in the film, in an unattractive manner, Clouzot pokes fun at the fetishism of style.

In the same scene, Clouzot further raises awareness of existence of the invisible cinematic apparatus that projects glamour and desire on the screen. The scene begins with a disorienting shot in washed-out whiteness. The light bulb on the upper left corner of the screen becomes discernable as Dora wields her lighting equipment to another direction away from the camera. These images are reminiscent of cinematographic projection and the experience of watching a movie, as traditionally the viewers would be sitting in a dark theatre and watching optically constructed images on the screen by virtue of a shaft of light from the projector. As the camera pans to track Dora as she approaches Jenny, Clouzot deliberates shows the several small pieces of lighting equipment positioned around Jenny. Evidently, the few small pieces of light equipment essentially are not capable of producing the abundant lighting that illuminates Jenny’s face and body. In a semi-revealing-of-device manner, Clouzot directs the attention of the viewer to the technology and the very process of mechanical production of images. With Jenny’s sickly-sweet photograph dietetically produced and overly sweet sentimentality spreads over the screen, it seems that the camera suggests to the viewer that the other glamorous images produced through the history of cinema are ultimately illusionary.

The composition of the shot where Dora stands by her lighting equipment also resonates with the opening scene, in which lights burst through the window of a smoky, dark cell from the upper left corner, spawning a sense of hopelessness and entrapment. The prison images not only function diegetically to create a dank atmosphere for the forthcoming crime and to foreshadow the fate of the murderer. Furthermore, invoking Plato’s allegory of the cave, the static images of dark cell become a metaphor for the film. As Jean-Louis Baudry maintains, “Plato’s prisoner is the victim of an illusion reality…he is the prey of an impression, of an impression of reality”. In this sense, a credulous spectator is the prisoner. Fascinated by the glamorous images, he or she embraces the romance between Jenny and Maurice and the engrossing policier in its totality. Quai des Orfèvres itself is producing an impression of reality, a mysterious dark underground world readily to be consumed by the viewer. However, Clouzot's self-conscious camera is also creating counter-images that bring the apparatus capable of fabricating such an impression reality to the forefront, to visualize the invisible and remind the spectator of the images’ illusionary nature. In another place, self-reflectively, Clouzot has a police officer shout out “not in the river!” in surprise as Maurice tells the policemen his gun, which is considered as the gun Maurice uses that kills Brignon, is at home. Referring to the common trope, it is as if Clouzot almost intended to have someone shout out that this was only a movie.

As one scrutinizes the film, it is also not difficult to discern the two-faced, complex nature of the town and its inhabitants: the modern, independent lesbian Dora takes naked photographs of young women to make money, and her sweater with her name inscribed begs for attention; the meek husband Maurice is actually a man of great passion, capable of executing a passion crime; the sardonic, world-weary investigator Antoine nevertheless harbors kindness for others and cares deeply for the adopted mulatto kid; the romance between Jenney and Maurice, while may be genuine, is often only manifested by their fulsome protestations of their love. Here, Clouzot offers a meticulously three-dimensional and almost Balzacian study of men and women, and invites the viewer to celebrate the diversity of humankind while acknowledging its dark yearnings, unsatisfied desires, and despair. Clouzot is not an ascetic, but he does not grant the spectator access to consuming the sentimental optimism and hope without a grain of despair and dissatisfaction. In the original novel, the wife is the murderer. Clouzot re-worked the ending. In the film, Paolo miraculously enters the narrative to exempts Jenny and Maurice from prison time. However, the view still needs to see Maurice commit suicide while the Christmas bell ringing merrily and to see the graphic images of his blood flowing through cracks of prison wall in order to get to the happy ending.

Works Cited

Baudry, Jean-L., “The Apparatus: Metapsychological Approaches to the Impression of Reality in Cinema,” In Film Theory and Criticism, edited by L. Braudy and M. Cohen, 690-707. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Bianchi, Pietro and Mignani, Rigo. “Henri-Georges Clouzot,” Yale French Studies 17 (1956), 21-26.

Mayne, Judith. “Dora the image-maker, and Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Quai des Orfèvres,” Studies in French Cinema 4 (2004), 41-52.

By Aimée

For his collaboration with the Continental during the Occupation when he made Le Corbeau (1943), Henri-Georges Clouzot was barred from filmmaking for four years. After the sanctions were lifted, Clouzot returned with a dazzling piece of comedie humaine: Quai des Orfèvres (1947). The film features an ambitious chanteuse Jenny and her hapless pianist-accompanist husband Maurice who find themselves involved in the murder of a lecherous admirer of Jenny’s. Eventually, a minor character Paolo is found guilty of the crime. After Maurice is released from prison to return home, the couple celebrates a happy Christmas together. If one takes Quai des Orfèvres at face value, the film can be read as a conventional Christmas tale with an unsurprising ending. However, a closer look at the film’s characterization and aesthetic choices suggests otherwise. The multi-layered, self-reflective film essentially resists the sentimental optimism that its Hollywood counterparts persist to promote and calls into question the fetishism of glamour and style. Clouzot further directs the spectator’s gaze onto a disenchanting world of desires and despair, and places the cinematic apparatus that produces the desires under examination.

The film presents the spectator with a study of man and women, of their desires and despair. The arriviste torch singer Jenny is constructed as the center of desires. The first time the spectator encounters Jenny is through Maurice’s surveillant yet lustful gaze. In a point of view shot, the viewer discovers Jenny sitting confidently on the table with her legs half-covered by a luxurious fur coat while she is practicing her Belle Époque-reviving risqué songs on the side of a flirtatious music producer. Maurice desires Jenny but is often overshadowed by her other more resourceful admirers. Imbued with jealousy and despair, Maurice eventually resorts to his murderous impulse. In the following shots bridged by Jenny’s alluring delivery of the voluptuous song “Avec son tra-la-la”, the viewer soon discovers another admirer Dora, who is smoking and fixatedly gazes at Jenny. It later becomes explicit that Dora has feelings for Jenny but her love is without hope and will never be requited. In the subsequent shot from Dora’s point of view, the viewer finds Jenny practicing the song in a three-way mirror and stares at the fragmented, multiplied images of herself, as if she desires her own images. The accumulation of desires finally reaches its peak as Jenny performs on the stage, exciting her audience with bubbly lines and apt body dynamics. Jenny actively seeks others’ gazes and derives pleasure in being looked at, for she believes her sexual energy and desirability will help her secure fame and money. But eventually her desire for becoming a movie star is unrealized. In one way or another, Jenny, Maurice, and Dora all become involved in the murder of Brignon because of their desires for something, whether it is love, sex, fame, or capital. Clouzot’s camera articulates the play of desires. As the film progresses, the desires create immense troubles for his characters.

It may seem that Clouzot is recycling the most widely used tropes and unimaginatively uses cinematic devices that belong to the inventory of classical Hollywood cinema from the early-to-mid century. However, while sharing some basis in narrative and aesthetics, Quai des Orfèvres differs from its Hollywood counterparts at a fundamental level for its subversive practice that aims to negate pleasure and casts ridicule on the fetishism itself. Such subversion is evidenced by Clouzot’s malicious choice of casting Simone Renant as a lesbian in plaid knit sweater, thick wool trousers, and other airtight unattractive plain clothes – a character that resists fetishistic gazes. Apart from two close-up shots that glamorize Renant’s face, Clouzot’s camera does not give the spectator access to fetishizing the body of the “highly elegant, blond and pink apparition, who at the time was regarded as the most beautiful actress in Paris” . Moreover, Renant with her eye-catching blondness and dress in American style functions as a stand-in for Hollywood fetish stars. However, by denying access to her body and glamor, Clouzot inverts her role and uses her images precisely to resist “the very objectification she appears to embody.” Another example is Jenny’s photograph that Dora takes for an American magazine. In the well-lit room where everything radiates glamour, Jenny fakes to cover her chest with her hand and strikes a mawkish lover-girl pose when Dora presses the shutter. The saccharine image is more idiotic than attractive. By framing Jenny, the supposedly most attractive and alluring female in the film, in an unattractive manner, Clouzot pokes fun at the fetishism of style.

In the same scene, Clouzot further raises awareness of existence of the invisible cinematic apparatus that projects glamour and desire on the screen. The scene begins with a disorienting shot in washed-out whiteness. The light bulb on the upper left corner of the screen becomes discernable as Dora wields her lighting equipment to another direction away from the camera. These images are reminiscent of cinematographic projection and the experience of watching a movie, as traditionally the viewers would be sitting in a dark theatre and watching optically constructed images on the screen by virtue of a shaft of light from the projector. As the camera pans to track Dora as she approaches Jenny, Clouzot deliberates shows the several small pieces of lighting equipment positioned around Jenny. Evidently, the few small pieces of light equipment essentially are not capable of producing the abundant lighting that illuminates Jenny’s face and body. In a semi-revealing-of-device manner, Clouzot directs the attention of the viewer to the technology and the very process of mechanical production of images. With Jenny’s sickly-sweet photograph dietetically produced and overly sweet sentimentality spreads over the screen, it seems that the camera suggests to the viewer that the other glamorous images produced through the history of cinema are ultimately illusionary.

The composition of the shot where Dora stands by her lighting equipment also resonates with the opening scene, in which lights burst through the window of a smoky, dark cell from the upper left corner, spawning a sense of hopelessness and entrapment. The prison images not only function diegetically to create a dank atmosphere for the forthcoming crime and to foreshadow the fate of the murderer. Furthermore, invoking Plato’s allegory of the cave, the static images of dark cell become a metaphor for the film. As Jean-Louis Baudry maintains, “Plato’s prisoner is the victim of an illusion reality…he is the prey of an impression, of an impression of reality”. In this sense, a credulous spectator is the prisoner. Fascinated by the glamorous images, he or she embraces the romance between Jenny and Maurice and the engrossing policier in its totality. Quai des Orfèvres itself is producing an impression of reality, a mysterious dark underground world readily to be consumed by the viewer. However, Clouzot's self-conscious camera is also creating counter-images that bring the apparatus capable of fabricating such an impression reality to the forefront, to visualize the invisible and remind the spectator of the images’ illusionary nature. In another place, self-reflectively, Clouzot has a police officer shout out “not in the river!” in surprise as Maurice tells the policemen his gun, which is considered as the gun Maurice uses that kills Brignon, is at home. Referring to the common trope, it is as if Clouzot almost intended to have someone shout out that this was only a movie.

As one scrutinizes the film, it is also not difficult to discern the two-faced, complex nature of the town and its inhabitants: the modern, independent lesbian Dora takes naked photographs of young women to make money, and her sweater with her name inscribed begs for attention; the meek husband Maurice is actually a man of great passion, capable of executing a passion crime; the sardonic, world-weary investigator Antoine nevertheless harbors kindness for others and cares deeply for the adopted mulatto kid; the romance between Jenney and Maurice, while may be genuine, is often only manifested by their fulsome protestations of their love. Here, Clouzot offers a meticulously three-dimensional and almost Balzacian study of men and women, and invites the viewer to celebrate the diversity of humankind while acknowledging its dark yearnings, unsatisfied desires, and despair. Clouzot is not an ascetic, but he does not grant the spectator access to consuming the sentimental optimism and hope without a grain of despair and dissatisfaction. In the original novel, the wife is the murderer. Clouzot re-worked the ending. In the film, Paolo miraculously enters the narrative to exempts Jenny and Maurice from prison time. However, the view still needs to see Maurice commit suicide while the Christmas bell ringing merrily and to see the graphic images of his blood flowing through cracks of prison wall in order to get to the happy ending.

Works Cited

Baudry, Jean-L., “The Apparatus: Metapsychological Approaches to the Impression of Reality in Cinema,” In Film Theory and Criticism, edited by L. Braudy and M. Cohen, 690-707. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Bianchi, Pietro and Mignani, Rigo. “Henri-Georges Clouzot,” Yale French Studies 17 (1956), 21-26.

Mayne, Judith. “Dora the image-maker, and Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Quai des Orfèvres,” Studies in French Cinema 4 (2004), 41-52.

雖然個中情節如今觀來著實有點小兒科 不過這幾個人物塑造得那個真叫有血有肉啊

悬念欠少许,情节推进中规中矩。波澜不惊的剧情,令人憧憬的光明收场。对劳动阶级的描述是全片的亮点:被贿赂的偷车贼、大晒人力成本对政府抱怨的警长,同时也从侧面反映了当时糟糕的治安状况。相对而言,本片更具有意大利现实主义特色,而不像自法国出土。

黑色悲喜剧,克鲁佐在战后还是拍了这样不那么阴暗的故事,所以看起来比较不像,有受意大利的影响。开篇比较散,光顾着活跃气氛了,但是进入正题之后还是好,尤其室内戏,尤其后半段。几个配乐很突兀,但也尚可。整体略微亚于巅峰时期。

maybe this is the one that has fewest tension or suspense plots among the four of his films released by CC, but it's still a good movie.

保持原汁原味的同时,设计了大众喜闻乐见的圆满结局,为实现战后欧洲资本主义社会和谐做出了突出贡献。

学习了弱关联元素的运动。另外,不是贫穷的杂耍艺人。丈夫是富裕家庭出身,他们的房子也是大房子啊。

布局精巧,细节丰富,人物立体,大赞!

里面每一个角色出现时都不仅仅为剧情主线服务,他们总要针对自己的生活世界抱怨一通,让全片显得更有生气

看好多人,我总感觉他们像胖子,即便事实上他们不像。唉。片子悬疑不够,不过音乐场面不错的。

本片的类型还是更偏向犯罪片,悬疑感相对有些弱,不过人物的塑造还是很立体的,在赞颂善良的同时也看到了他们的人性弱点。

感觉不怎么克鲁佐啊,很不像,不悲惨也不黑色更不法式希区,,

斜风细雨没带伞@打浦桥 久闻克鲁佐暗影重重 乌鸦亦是被期待久长的心头好 然而到底今日始得debut囧 年代背景下看这片节奏在法语片里算是很紧凑了 谜底的揭晓看似也无玄虚 镜头和编排上都少有花哨之处 在时事的压迫之下却以平铺方式赚得全局观 对人物的刻画尤见火候 音乐女同也出彩 佩服

这更像一部平庸的现实主义电影,而非一个悬疑或者黑色电影,再加上模糊的结构和弱不禁风的角色,整体观感涣散无聊,很不克鲁佐

我们都在期待复杂的故事,没想到却是最普通的结局。喜欢同性之爱那条线。

引入了好莱坞制作,相比恶魔,悬疑的气氛差了很多,结尾来得太快,罪犯出现的也很突兀,除了警长最后那句耐人寻味的话“我和你对女人都是没机会的”。

光影极佳,意境正美实传统元素的继承;没有了《乌鸦》的悬疑诡气,但是仍然作足了心理分析

典型的人物(风骚的女主与善妒的男主)又不乏迷人的配角(女摄影师和探长)和台词,报纸点烟一节的悬疑营造很像希区柯克,视听上印象最深的是平安夜象征赎罪的钟声和不时出现的影子。其实整体气质包括配乐更近好莱坞,也确实好看。所有人都到过现场还声称自己是凶手其实都不是,颇有点剧本杀雏形的意思。8.5/10

分明像一部给『虎胆龙威』来了个性别反转的圣诞电影。描绘起一片萧条,生活艰辛的战后法国,其中的批评与戏讽依然仅止步于世态,而拒不指摘人心。叙事之高效以及塑造人物时的斟酌实在让人叹为观止,即使不过两三句台词的角色也是个个鲜活。此外克鲁佐不乏刻薄的幽默感绝对被低估。

能把一部黑色电影拍出贺岁片结局,这本身就是一个圣诞奇迹

“一提到女人,我们都没有机会”,这样的对白实在迷人,一边是一心办大案却始终碌碌无为的侦探,另一边是有同性恋倾向的女主闺蜜。而明面上的男女主角到最后与案件并没有直接关系,极具讽刺意味的黑色喜剧。