更新时间:2023-09-01 16:23

详细剧情

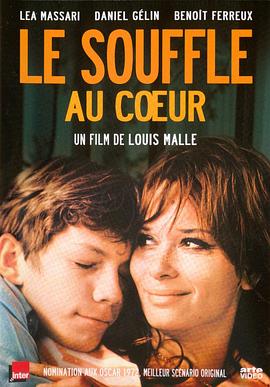

作为家中最小的儿子,罗伦特(贝努阿·费雷 Benoît Ferreux 饰)理所应当的享受着更多的照顾和关怀。罗伦特的母亲克拉拉(蕾雅·马萨利 Lea Massari 饰)是一个思想和作风都颇为开放的意大利人,这给罗伦特的成长史打上了不可磨灭的印记。罗伦特就读于一所校风极其严谨的天主教学校,在压抑和束缚之中,十五岁的罗伦特开始对“性”产生了兴趣。

长篇影评

1 ) 这位母亲的心和爱真正自由的

事发后......

——“我不要你为这件事感到不开心,羞耻或后悔,我们要以此作为很美的、庄严的一瞬间留在记忆中。但它永远不会再发生。没什么,我们再也不会提起,这是我们间的秘密。我会毫无责任地体贴地记住它,答应我,你也会这么做。”

全片最棒的一句台词。母子乱伦最佳案例没有之一。

结尾处男生去找其他人本来还不懂,看到最后简直为不知道是男孩本身成长后的聪明,还是导演设定的聪明,拍案叫绝啊。

最后 泰迪一家结尾的大笑简直是经典至极。一家都乱搞,一家都能以笑化解,相信以后也会继续乱搞。模范先驱是母亲,哥哥带弟弟,不过弟弟的身体比嘴上诚实多了,如片中那位妓女所说,“等你大点的时候会是个多情种”。

BTW 结尾全家大笑镜头中母亲咬手指的动作太赞。将那种与儿子才发生过关系后第二天那种有点纠结矛盾看见儿子尴尬又暧昧的姿态完全体现出来。

全片没有伦理片一贯那种极端、极端绝望、阴暗的氛围,结尾也是以化解尴尬的大笑收场。导演同时也在暗示母亲和儿子间的那种东西最终也会以轻松、相互的理解、成长收场。而一切的原因都是因为母亲本人的性格。在她身上体现了真正#自由的爱#。不受到任何伦理社会教条的束缚,脱离了一切后天的固话的僵化的社会化思想,她的身上有一种近乎原始的自由,她的心是真正自由的、公正的,在她从心所欲又并不表现得浪荡堕落的背后,是源自她身上充斥着的强烈的爱。

人原本是原始的、生物的,而所谓文明的发展就是加入了很多后天的社会化的东西在里面。这样的约束的确一定程度上保证了人类社会生活的稳定,但另一方面也不可避免制约了人类的本性,为了更高层的发展和文明,一些自发的东西必须要舍弃。就如同为了基因的优良,近亲繁殖必须禁止,这是畸形婴出现的教训。就如同越是发达的资本主义国家,人与人之间有一种接近于冷漠的礼貌,这是因为人类天然的好奇心和窥探欲会侵害隐私。

而很多时候,爱让人痛苦,也是源自这些外在的社会化条款。人的性别被限制、阶层被限制、血缘被限制,有的时候种族被限制,因为宗教也被限制。这些限制无一例外出自两方面,一是先天生理上的残缺,繁育和培育更优良品质这一人类繁衍生息的原始目标被破坏。二十后天社会上的利益损伤,人的一切活动都围绕利己产生,财产、名誉这两大世俗标准被损害。因为这先天和后天这两方面原因,人的感情很多时候受到限制。所以,作为社会规则下衍生的名词,才出现禁忌恋的说法。同性恋、母子恋、兄妹恋,在一定社会时期黑人打破规则与白人相恋,穆斯林与外族人相恋......而在这一系列的禁忌恋中,破坏了社会规则的恋情(如因为阶层、宗教)依据地理地点、历史时期而可能出现更变,相对也较好。而真正严重、最受到谴责和强烈内疚感罪恶感的,是破坏生物性的恋情(母子恋、父女恋等有血缘关系的),原本想拉上同性恋,但最近形式已经改善很多了。可能是因为比起生出让人厌恶的畸形婴,同性恋是并不会产生什么实质上恶果,这样的“无为”也让人难以真正将让其坐上罪证。

回到片中,其实这个泰迪一家都是过着这样的生活。看似上层体面的家族,儿子是学校学习上的优等生宗教上的模范代表,人人称目的好学生,还是那考上大学仪表堂堂的哥哥,再加上那个片中一笔带过的实则娶了毫无身份因为一夜情未婚先育16岁母亲的医生。在社会规则下明显处于优势的一家,实则背后个个无视这套规则。母亲是代表,不然哪来的后面三个内在跟她模板刻出只是表现形式稍不同的儿子。

就说社会上,“幻想”过母亲的儿子一定不在少数,但能够相片中男孩一样跟母亲“一夜泯恩仇”,然后迅速去找到其他女孩证明自己可以长大的男生是少数。大多数人,带着那个“俄狄浦斯情结”,懦弱得变成了个妈宝男。

所以本片大赞。歌颂这自由的母子之爱。

——“我不要你为这件事感到不开心,羞耻或后悔,我们要以此作为很美的、庄严的一瞬间留在记忆中。但它永远不会再发生。没什么,我们再也不会提起,这是我们间的秘密。我会毫无责任地体贴地记住它,答应我,你也会这么做。”

全片最棒的一句台词。母子乱伦最佳案例没有之一。

结尾处男生去找其他人本来还不懂,看到最后简直为不知道是男孩本身成长后的聪明,还是导演设定的聪明,拍案叫绝啊。

最后 泰迪一家结尾的大笑简直是经典至极。一家都乱搞,一家都能以笑化解,相信以后也会继续乱搞。模范先驱是母亲,哥哥带弟弟,不过弟弟的身体比嘴上诚实多了,如片中那位妓女所说,“等你大点的时候会是个多情种”。

BTW 结尾全家大笑镜头中母亲咬手指的动作太赞。将那种与儿子才发生过关系后第二天那种有点纠结矛盾看见儿子尴尬又暧昧的姿态完全体现出来。

全片没有伦理片一贯那种极端、极端绝望、阴暗的氛围,结尾也是以化解尴尬的大笑收场。导演同时也在暗示母亲和儿子间的那种东西最终也会以轻松、相互的理解、成长收场。而一切的原因都是因为母亲本人的性格。在她身上体现了真正#自由的爱#。不受到任何伦理社会教条的束缚,脱离了一切后天的固话的僵化的社会化思想,她的身上有一种近乎原始的自由,她的心是真正自由的、公正的,在她从心所欲又并不表现得浪荡堕落的背后,是源自她身上充斥着的强烈的爱。

人原本是原始的、生物的,而所谓文明的发展就是加入了很多后天的社会化的东西在里面。这样的约束的确一定程度上保证了人类社会生活的稳定,但另一方面也不可避免制约了人类的本性,为了更高层的发展和文明,一些自发的东西必须要舍弃。就如同为了基因的优良,近亲繁殖必须禁止,这是畸形婴出现的教训。就如同越是发达的资本主义国家,人与人之间有一种接近于冷漠的礼貌,这是因为人类天然的好奇心和窥探欲会侵害隐私。

而很多时候,爱让人痛苦,也是源自这些外在的社会化条款。人的性别被限制、阶层被限制、血缘被限制,有的时候种族被限制,因为宗教也被限制。这些限制无一例外出自两方面,一是先天生理上的残缺,繁育和培育更优良品质这一人类繁衍生息的原始目标被破坏。二十后天社会上的利益损伤,人的一切活动都围绕利己产生,财产、名誉这两大世俗标准被损害。因为这先天和后天这两方面原因,人的感情很多时候受到限制。所以,作为社会规则下衍生的名词,才出现禁忌恋的说法。同性恋、母子恋、兄妹恋,在一定社会时期黑人打破规则与白人相恋,穆斯林与外族人相恋......而在这一系列的禁忌恋中,破坏了社会规则的恋情(如因为阶层、宗教)依据地理地点、历史时期而可能出现更变,相对也较好。而真正严重、最受到谴责和强烈内疚感罪恶感的,是破坏生物性的恋情(母子恋、父女恋等有血缘关系的),原本想拉上同性恋,但最近形式已经改善很多了。可能是因为比起生出让人厌恶的畸形婴,同性恋是并不会产生什么实质上恶果,这样的“无为”也让人难以真正将让其坐上罪证。

回到片中,其实这个泰迪一家都是过着这样的生活。看似上层体面的家族,儿子是学校学习上的优等生宗教上的模范代表,人人称目的好学生,还是那考上大学仪表堂堂的哥哥,再加上那个片中一笔带过的实则娶了毫无身份因为一夜情未婚先育16岁母亲的医生。在社会规则下明显处于优势的一家,实则背后个个无视这套规则。母亲是代表,不然哪来的后面三个内在跟她模板刻出只是表现形式稍不同的儿子。

就说社会上,“幻想”过母亲的儿子一定不在少数,但能够相片中男孩一样跟母亲“一夜泯恩仇”,然后迅速去找到其他女孩证明自己可以长大的男生是少数。大多数人,带着那个“俄狄浦斯情结”,懦弱得变成了个妈宝男。

所以本片大赞。歌颂这自由的母子之爱。

2 ) 只是好奇的心

一个有才华的,典型的中产阶级家庭长大的小男孩。有着与其他同龄少男少女一样的好奇心。

而且这些好奇与尝试仅仅是认识世界的一个过程而已。

尽管有着强烈的好奇心,但是,我猜他最终的人生轨迹应该会是如他父亲一样的成功且循规蹈矩。

只是少年时期的短暂回忆罢了。影片结尾说明了一切。

而且这些好奇与尝试仅仅是认识世界的一个过程而已。

尽管有着强烈的好奇心,但是,我猜他最终的人生轨迹应该会是如他父亲一样的成功且循规蹈矩。

只是少年时期的短暂回忆罢了。影片结尾说明了一切。

3 ) 人们可以彼此尊重到什么程度?

人们可以彼此尊重到什么程度?

电影里的男孩儿纵容了妈妈的外遇,心里也老大不乐意。但是他依然将这一切容忍,他和美丽的母亲结成了同盟——

“无论你做什么,我都会支持你。”

我把它理解为“尊重”——尊重你心爱的人的自由,尊重你心爱的人的爱情,尊重你心爱的人的心愿。但是请注意这个人是你的家人是你的爹妈是你的血亲。

还假装无动于衷呢。

要是纯嫉妒也不对,那是男孩的父亲该做的事儿,即使他自己也确实在嫉妒——

“你像个小丈夫,法兰西小丈夫!”她妈妈这样笑他。

关键是,男孩儿并没把这些事儿视为“背叛”,这一切反倒成为他和他漂亮老妈之间推心置腹的资本。

什么恋母啊什么乱伦啊我也懒得去探究了,我只是好奇他们的底线到底在哪里。

我觉得这种因爱而生的宠溺和纵容已经有些可怕,因为爱到连占有欲都不见了。即使他们是母子,他们也是独立的个体,互相尊重互不干涉。

这个男孩儿——噢,应该说这些男孩儿,他们教养良好,懂得优雅,精通叛逆。可以把隐私拿来当游戏。一个个还霸道傲慢的恰到好处。火候拿捏的神准,真可怕。

我看不到底线,他们都无比优雅挺胸昂头的活着。这多么好。

也多么让人难过。

电影里的男孩儿纵容了妈妈的外遇,心里也老大不乐意。但是他依然将这一切容忍,他和美丽的母亲结成了同盟——

“无论你做什么,我都会支持你。”

我把它理解为“尊重”——尊重你心爱的人的自由,尊重你心爱的人的爱情,尊重你心爱的人的心愿。但是请注意这个人是你的家人是你的爹妈是你的血亲。

还假装无动于衷呢。

要是纯嫉妒也不对,那是男孩的父亲该做的事儿,即使他自己也确实在嫉妒——

“你像个小丈夫,法兰西小丈夫!”她妈妈这样笑他。

关键是,男孩儿并没把这些事儿视为“背叛”,这一切反倒成为他和他漂亮老妈之间推心置腹的资本。

什么恋母啊什么乱伦啊我也懒得去探究了,我只是好奇他们的底线到底在哪里。

我觉得这种因爱而生的宠溺和纵容已经有些可怕,因为爱到连占有欲都不见了。即使他们是母子,他们也是独立的个体,互相尊重互不干涉。

这个男孩儿——噢,应该说这些男孩儿,他们教养良好,懂得优雅,精通叛逆。可以把隐私拿来当游戏。一个个还霸道傲慢的恰到好处。火候拿捏的神准,真可怕。

我看不到底线,他们都无比优雅挺胸昂头的活着。这多么好。

也多么让人难过。

4 ) Murmur of the Heart: All in the Family

Murmur of the Heart: All in the Family

By Michael Sragow

Murmur of the Heart (1971), Louis Malle’s comic masterpiece, is the most American of great French films. Indeed, with its youthful charm and rebellion, the film feels even more characteristically American than the mature and elusive masterpieces Malle went on to direct in America—Atlantic City, in 1980; My Dinner with Andre, the following year; and Vanya on 42nd Street, in 1994. From the start of his career, aspects of U.S. culture had always brought a special resonance to Malle’s movies: a Miles Davis soundtrack ignites Elevator to the Gallows (1957); the tiny heroine of Zazie dans le métro (1960) buys American jeans; the suicidal hero of The Fire Within (1963) chooses F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby to be the final thing he reads. But Malle continually carbonates Murmur of the Heart with a Yankee-flavored fizz. Jazz by Charlie Parker and others fills the soundtrack. Visual and verbal references to American popular culture abound. Most importantly, Malle’s free-for-all view of haute-bourgeois family life has an American-style spontaneity and rambunctiousness. The adolescents in this film may be chic, but they’re iconoclastic, too. And even though the movie depicts psychologically charged material—including incest—that would normally resist comic handling, Malle gives the whole shebang a crackpot symmetry worthy of Hollywood screwball comedy at its peak.

Murmur of the Heart was, in fact, a turning point for Malle—or, rather, the turning point after a turning point. Malle emerged into world cinema seemingly full-grown, as a sleek craftsman boasting a rangy intelligence and stylistic invention and audacity. Whether codirecting Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s marine documentary The Silent World (1956); creating an inspired erotic update of an eighteenth-century short story (The Lovers [1958], from “No Tomorrow,” by Vivant Denon); or keenly rendering modern classics (Zazie dans le métro, from Raymond Queneau’s novel), Malle appeared to be the kind of director who became “personal” by melding his sensibility with that of a primary author. (Even Elevator to the Gallows comes from a thriller by Noel Calef.)

Yet his best movies pivoted on signature moments of violent or chaotic release—there was always a volatile temperament simmering under that virtuoso surface. After the frolic of Viva Maria! (1965) and the period adaptation The Thief (1966), however, Malle began to worry that he might become a cliché: one more accomplished French director putting out a worthy picture every year. Mentally blocked from tackling, head-on, autobiographical material or incendiary political subjects, yet too antsy and ambitious to settle into complacent professionalism, Malle took an extraordinary step. In 1968, without any set shooting plan or preconceived notions, he journeyed to India with a soundman and a cameraman, submerged himself in the society and the culture, and came out with the material for the theatrical documentary Calcutta (1969) and the seven-part TV series Phantom India (1969). “I think this experience of relying on my instincts was quite decisive in my work,” Malle told Philip French, in the early nineties. “I’ve always tried to rediscover the state of innocence that I found so extraordinary working in India.”

This new reliance on hunch and intuition empowered Malle to reach further down into himself and confront his most intimate concerns. It would take him years to relate, in Au revoir les enfants (1987), the wartime trauma that had haunted him since childhood—the Nazis’ arrest of a Jewish classmate posing as a gentile in Malle’s Catholic boarding school. But starting with Murmur of the Heart, he began operating as an archaeologist of his own heart, putting together insights and observations from every era that he had lived through and exposing his own most personal reactions to fraught or perilous circumstances. The complexity of his portrait of a young French collaborator in World War II, Lacombe, Lucien (1974), derives as much from his earlier, aborted attempt to grapple with his countrymen’s colonial battles in Algiers (in 1962, at age thirty, he spent twenty-four hours in a fortress in east Algeria, then found the subject too incendiary) as it does from his experiences as a boy in occupied France.

What’s remarkable about Malle’s portraits of youth—what allows him to tap bottomless wells of humor and pathos—is that they’re both empathetic and pitiless. Zazie is a one-girl youth movement, as exhausting as she is exhilarating. The movie dares you to keep up with her, and Malle’s artistry transforms it into a happy challenge. Lucien Lacombe swings almost arbitrarily from potential Resistance fighter to collaborator, from coexecutioner to savior of his Jewish lover and her grandmother; we eventually see him as an overgrown feral child. Malle is ruthlessly objective about his alter ego in Au revoir les enfants, right up to the moment when his furtive glance at his Jewish pal reveals the lad’s identity to the Nazis—who, of course, would have caught the poor boy anyway.

Murmur of the Heart offers an unusually full and individualized characterization of a boy whose yearnings, sensitivities, and fantasies outstrip his personality—the sort of unformed figure that creators less bold, candid, or inventive than Malle would never dare to present as their surrogate. The director told French that the setup for Murmur of the Heart was autobiographical: “My passion for jazz, my curiosity about literature, the tyranny of my two elder brothers, how they introduced me to sex—this is pretty close to home. And when I got this heart murmur, the doctors said to my mother, ‘You have to take him to this spa, that’s the best thing you can do.’” For “bizarre” reasons, they did end up sharing the same room. But everything else was invented, including the details of growing up in the 1950s, during the French downfall in Indochina, engendered by Dien Bien Phu. (Malle, of course, grew up in the 1930s and ’40s.)

Still, the atmosphere in Murmur of the Heart is hyperrealistic. It’s seductive and hilarious, as well, because of the warmth and unexpected eccentricity of the moviemaker’s observations. Malle’s fourteen-year-old hero, Laurent (played by Benoît Ferreux), has a taste for Albert Camus that upsets his Catholic schoolteachers and a yen for jazz that helps him bebop to a different drummer. Ferreux offers the perfect image for Laurent: his legs seem too long for his body, and his head too big for it; his expressions of mischief and of petulance, or even rage, are all equally beguiling. The whole movie is built on Laurent’s inchoate nature and the way it makes him, as his adoring mother puts it, unpredictable. Malle doesn’t commit the error of setting him too far apart from the other children in his class, or from his frolicsome older brothers. But the director gets across how Laurent’s imagination imbues him with more vulnerability and awareness, and also more charisma, than the others. (You can see why a little blond boy develops an innocent crush on him.)

A lot of Laurent’s distinctiveness comes out in the writing. Malle hands him lines replete with deadpan derision, and Ferreux delivers them with innocent insouciance—as though he were the first freshman or sophomore to discover the pleasures of the put-down. He’s funny when urging a recalcitrant record-shop owner (from whom he’s just shoplifted) to donate money “for France,” to support the wounded in Indochina. He’s funnier when outraging propriety-obsessed mothers at a spa by telling them that all of their daughters are lesbians, and that one of their sons told him so. But just as much of Laurent’s infectious quality comes from his off-kilter visual impression. His gangling, thin-stemmed coltishness doesn’t quite keep pace with the determined-to-be-cool looks that steal across his shrewd, observant, sometimes bemused face.

Laurent and his brothers mesh with their mother, Clara (Leá Massari), more than they do with their gynecologist father, Dr. Charles Chevalier (Daniel Gélin). The movie rebuts the Father Knows Best caricatures that have pervaded bourgeois pop culture everywhere; Malle knows that, in even the most pretentious families (perhaps in those especially), the wife and servants and sons know Father’s strengths and limitations all too well. The name Dr. Chevalier, with its reference to the lowest rank of the French Legion of Honor, mocks upper-middle-class social aspirations. He’s proud of a Corot he found in the attic; but his eldest sons have it forged, just for the elation of knowing that their old man can’t tell the difference between the original and the copy, which leads to a delicious, heart-stopping practical joke. Yet the father isn’t an ignoble man. He’s just resigned beyond his years.

With the vibrant Massari giving one of the great performances of the seventies, Clara is the character who, along with Laurent, dominates the household and the film. This passionate Italian, who grew up as the daughter of a rebellious father, says she fell for Chevalier because, with a beard, he looked like Garibaldi. She’s got a voracious appetite for sensual pleasure and freedom. She can’t help treating her sons as playmates; when she discovers them filching her money, the result is nothing more serious than a game of monkey-in-the-middle, played in her bedroom, with her as the monkey. When Laurent first discovers that Clara has a lover, he’s stricken. He runs to his father, who shoos him out of the office before he can say anything. With his heart and mind in turmoil, he’s further confused when his brothers pay for his initiation into sex with a friendly, compliant prostitute, and then, in a drunken prank, pull him off prematurely. The murmur of the heart in the title is literally the heart murmur that Laurent develops after a fever, but metaphorically it stands for the way that a sensitive adolescent’s life can seem to skip a beat. (Fittingly, the English title for Jacques Audiard’s engaging remake of James Toback’s seminal Fingers—the tale of an adolescent arrested in extremis—was The Beat That My Heart Skipped. Might Audiard have had Malle in mind, too?) Laurent and Clara move ever closer to each other during his convalescence. They go off to a spa, where they’re forced to share close quarters because of a mistake in booking. They turn from mother and son, or even friends, to soul mates. She recognizes his frustration as he comes on to a couple of pretty young patients, while he gets nearer than he wants to one of her final liaisons with her lover. For mother and son, their inebriated celebration of Bastille Day becomes a time of emotional liberation. They make love in the least incestuous incest scene imaginable. There’s no Bertolucci-like portentousness. Malle doesn’t treat it as a taboo—he ties it too closely to the needs and dreams of a drunken, amorous woman who’s still dizzy from her breakup with her lover, and of a drunken, amorous teenager who has grown to understand the emotional needs behind her adultery. Rather than set off damaging psychic depth charges, the experience gives Laurent an unexpected shot of virility. Almost immediately afterward, he goes on a night prowl for those two girls, and gets lucky with one of them. That’s true to the extroverted spirit of the whole movie. Malle doesn’t merely ridicule the clannishness and cliquishness of middle-class life; he turns those qualities inside out. The home-as-castle conservatism of the father joins with the anything-goes fervor of the mother to give their kids a springboard resilience. When they carry on like spoiled brats, playing “spinach tennis” at the dinner table while their parents are away, or rolling up the rugs for a dance party, they aren’t just being fresh—they’re filling the house with fresh air.

In Murmur of the Heart, Malle’s own zest connects with the knockabout wit and curiosity of his adolescent antiheroes. He sketches even the jokey supporting parts with a satiric sort of sympathy—like the youthful snob Hubert (François Werner), who thinks it’s classy and worldly to defend colonialism. From the fleshy warmth of Ricardo Aronovich’s cinematography to the jazz percolating in Laurent’s brainpan—and, thanks to Malle, in ours—the movie boasts the high spirits to match its high intelligence. Murmur of the Heart is the opposite of a problem comedy about incest. For one thing, incest is not a problem here. Incest is the trapdoor that swings up to reveal the turbulence beneath a cozy way of life—and, in doing so, betrays the growing appetite for candor of a towering twentieth-century artist.

Michael Sragow has been the lead critic of the Baltimore Sun since 2001

By Michael Sragow

Murmur of the Heart (1971), Louis Malle’s comic masterpiece, is the most American of great French films. Indeed, with its youthful charm and rebellion, the film feels even more characteristically American than the mature and elusive masterpieces Malle went on to direct in America—Atlantic City, in 1980; My Dinner with Andre, the following year; and Vanya on 42nd Street, in 1994. From the start of his career, aspects of U.S. culture had always brought a special resonance to Malle’s movies: a Miles Davis soundtrack ignites Elevator to the Gallows (1957); the tiny heroine of Zazie dans le métro (1960) buys American jeans; the suicidal hero of The Fire Within (1963) chooses F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby to be the final thing he reads. But Malle continually carbonates Murmur of the Heart with a Yankee-flavored fizz. Jazz by Charlie Parker and others fills the soundtrack. Visual and verbal references to American popular culture abound. Most importantly, Malle’s free-for-all view of haute-bourgeois family life has an American-style spontaneity and rambunctiousness. The adolescents in this film may be chic, but they’re iconoclastic, too. And even though the movie depicts psychologically charged material—including incest—that would normally resist comic handling, Malle gives the whole shebang a crackpot symmetry worthy of Hollywood screwball comedy at its peak.

Murmur of the Heart was, in fact, a turning point for Malle—or, rather, the turning point after a turning point. Malle emerged into world cinema seemingly full-grown, as a sleek craftsman boasting a rangy intelligence and stylistic invention and audacity. Whether codirecting Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s marine documentary The Silent World (1956); creating an inspired erotic update of an eighteenth-century short story (The Lovers [1958], from “No Tomorrow,” by Vivant Denon); or keenly rendering modern classics (Zazie dans le métro, from Raymond Queneau’s novel), Malle appeared to be the kind of director who became “personal” by melding his sensibility with that of a primary author. (Even Elevator to the Gallows comes from a thriller by Noel Calef.)

Yet his best movies pivoted on signature moments of violent or chaotic release—there was always a volatile temperament simmering under that virtuoso surface. After the frolic of Viva Maria! (1965) and the period adaptation The Thief (1966), however, Malle began to worry that he might become a cliché: one more accomplished French director putting out a worthy picture every year. Mentally blocked from tackling, head-on, autobiographical material or incendiary political subjects, yet too antsy and ambitious to settle into complacent professionalism, Malle took an extraordinary step. In 1968, without any set shooting plan or preconceived notions, he journeyed to India with a soundman and a cameraman, submerged himself in the society and the culture, and came out with the material for the theatrical documentary Calcutta (1969) and the seven-part TV series Phantom India (1969). “I think this experience of relying on my instincts was quite decisive in my work,” Malle told Philip French, in the early nineties. “I’ve always tried to rediscover the state of innocence that I found so extraordinary working in India.”

This new reliance on hunch and intuition empowered Malle to reach further down into himself and confront his most intimate concerns. It would take him years to relate, in Au revoir les enfants (1987), the wartime trauma that had haunted him since childhood—the Nazis’ arrest of a Jewish classmate posing as a gentile in Malle’s Catholic boarding school. But starting with Murmur of the Heart, he began operating as an archaeologist of his own heart, putting together insights and observations from every era that he had lived through and exposing his own most personal reactions to fraught or perilous circumstances. The complexity of his portrait of a young French collaborator in World War II, Lacombe, Lucien (1974), derives as much from his earlier, aborted attempt to grapple with his countrymen’s colonial battles in Algiers (in 1962, at age thirty, he spent twenty-four hours in a fortress in east Algeria, then found the subject too incendiary) as it does from his experiences as a boy in occupied France.

What’s remarkable about Malle’s portraits of youth—what allows him to tap bottomless wells of humor and pathos—is that they’re both empathetic and pitiless. Zazie is a one-girl youth movement, as exhausting as she is exhilarating. The movie dares you to keep up with her, and Malle’s artistry transforms it into a happy challenge. Lucien Lacombe swings almost arbitrarily from potential Resistance fighter to collaborator, from coexecutioner to savior of his Jewish lover and her grandmother; we eventually see him as an overgrown feral child. Malle is ruthlessly objective about his alter ego in Au revoir les enfants, right up to the moment when his furtive glance at his Jewish pal reveals the lad’s identity to the Nazis—who, of course, would have caught the poor boy anyway.

Murmur of the Heart offers an unusually full and individualized characterization of a boy whose yearnings, sensitivities, and fantasies outstrip his personality—the sort of unformed figure that creators less bold, candid, or inventive than Malle would never dare to present as their surrogate. The director told French that the setup for Murmur of the Heart was autobiographical: “My passion for jazz, my curiosity about literature, the tyranny of my two elder brothers, how they introduced me to sex—this is pretty close to home. And when I got this heart murmur, the doctors said to my mother, ‘You have to take him to this spa, that’s the best thing you can do.’” For “bizarre” reasons, they did end up sharing the same room. But everything else was invented, including the details of growing up in the 1950s, during the French downfall in Indochina, engendered by Dien Bien Phu. (Malle, of course, grew up in the 1930s and ’40s.)

Still, the atmosphere in Murmur of the Heart is hyperrealistic. It’s seductive and hilarious, as well, because of the warmth and unexpected eccentricity of the moviemaker’s observations. Malle’s fourteen-year-old hero, Laurent (played by Benoît Ferreux), has a taste for Albert Camus that upsets his Catholic schoolteachers and a yen for jazz that helps him bebop to a different drummer. Ferreux offers the perfect image for Laurent: his legs seem too long for his body, and his head too big for it; his expressions of mischief and of petulance, or even rage, are all equally beguiling. The whole movie is built on Laurent’s inchoate nature and the way it makes him, as his adoring mother puts it, unpredictable. Malle doesn’t commit the error of setting him too far apart from the other children in his class, or from his frolicsome older brothers. But the director gets across how Laurent’s imagination imbues him with more vulnerability and awareness, and also more charisma, than the others. (You can see why a little blond boy develops an innocent crush on him.)

A lot of Laurent’s distinctiveness comes out in the writing. Malle hands him lines replete with deadpan derision, and Ferreux delivers them with innocent insouciance—as though he were the first freshman or sophomore to discover the pleasures of the put-down. He’s funny when urging a recalcitrant record-shop owner (from whom he’s just shoplifted) to donate money “for France,” to support the wounded in Indochina. He’s funnier when outraging propriety-obsessed mothers at a spa by telling them that all of their daughters are lesbians, and that one of their sons told him so. But just as much of Laurent’s infectious quality comes from his off-kilter visual impression. His gangling, thin-stemmed coltishness doesn’t quite keep pace with the determined-to-be-cool looks that steal across his shrewd, observant, sometimes bemused face.

Laurent and his brothers mesh with their mother, Clara (Leá Massari), more than they do with their gynecologist father, Dr. Charles Chevalier (Daniel Gélin). The movie rebuts the Father Knows Best caricatures that have pervaded bourgeois pop culture everywhere; Malle knows that, in even the most pretentious families (perhaps in those especially), the wife and servants and sons know Father’s strengths and limitations all too well. The name Dr. Chevalier, with its reference to the lowest rank of the French Legion of Honor, mocks upper-middle-class social aspirations. He’s proud of a Corot he found in the attic; but his eldest sons have it forged, just for the elation of knowing that their old man can’t tell the difference between the original and the copy, which leads to a delicious, heart-stopping practical joke. Yet the father isn’t an ignoble man. He’s just resigned beyond his years.

With the vibrant Massari giving one of the great performances of the seventies, Clara is the character who, along with Laurent, dominates the household and the film. This passionate Italian, who grew up as the daughter of a rebellious father, says she fell for Chevalier because, with a beard, he looked like Garibaldi. She’s got a voracious appetite for sensual pleasure and freedom. She can’t help treating her sons as playmates; when she discovers them filching her money, the result is nothing more serious than a game of monkey-in-the-middle, played in her bedroom, with her as the monkey. When Laurent first discovers that Clara has a lover, he’s stricken. He runs to his father, who shoos him out of the office before he can say anything. With his heart and mind in turmoil, he’s further confused when his brothers pay for his initiation into sex with a friendly, compliant prostitute, and then, in a drunken prank, pull him off prematurely. The murmur of the heart in the title is literally the heart murmur that Laurent develops after a fever, but metaphorically it stands for the way that a sensitive adolescent’s life can seem to skip a beat. (Fittingly, the English title for Jacques Audiard’s engaging remake of James Toback’s seminal Fingers—the tale of an adolescent arrested in extremis—was The Beat That My Heart Skipped. Might Audiard have had Malle in mind, too?) Laurent and Clara move ever closer to each other during his convalescence. They go off to a spa, where they’re forced to share close quarters because of a mistake in booking. They turn from mother and son, or even friends, to soul mates. She recognizes his frustration as he comes on to a couple of pretty young patients, while he gets nearer than he wants to one of her final liaisons with her lover. For mother and son, their inebriated celebration of Bastille Day becomes a time of emotional liberation. They make love in the least incestuous incest scene imaginable. There’s no Bertolucci-like portentousness. Malle doesn’t treat it as a taboo—he ties it too closely to the needs and dreams of a drunken, amorous woman who’s still dizzy from her breakup with her lover, and of a drunken, amorous teenager who has grown to understand the emotional needs behind her adultery. Rather than set off damaging psychic depth charges, the experience gives Laurent an unexpected shot of virility. Almost immediately afterward, he goes on a night prowl for those two girls, and gets lucky with one of them. That’s true to the extroverted spirit of the whole movie. Malle doesn’t merely ridicule the clannishness and cliquishness of middle-class life; he turns those qualities inside out. The home-as-castle conservatism of the father joins with the anything-goes fervor of the mother to give their kids a springboard resilience. When they carry on like spoiled brats, playing “spinach tennis” at the dinner table while their parents are away, or rolling up the rugs for a dance party, they aren’t just being fresh—they’re filling the house with fresh air.

In Murmur of the Heart, Malle’s own zest connects with the knockabout wit and curiosity of his adolescent antiheroes. He sketches even the jokey supporting parts with a satiric sort of sympathy—like the youthful snob Hubert (François Werner), who thinks it’s classy and worldly to defend colonialism. From the fleshy warmth of Ricardo Aronovich’s cinematography to the jazz percolating in Laurent’s brainpan—and, thanks to Malle, in ours—the movie boasts the high spirits to match its high intelligence. Murmur of the Heart is the opposite of a problem comedy about incest. For one thing, incest is not a problem here. Incest is the trapdoor that swings up to reveal the turbulence beneath a cozy way of life—and, in doing so, betrays the growing appetite for candor of a towering twentieth-century artist.

Michael Sragow has been the lead critic of the Baltimore Sun since 2001

5 ) 重审道德

对道德与自由的深度解构,对男孩青春期成长问题的完美托出,铺垫饱满,路易·马勒的叙事把控相当强大。长大之前,母亲是世界的镜像,一旦这个镜像被成长打破,男孩的视线将转移到其他异性,以替代对母亲的依恋。男孩一夜长大,开始寻花问柳,法国人用极其轻松、淡然、毫无负担的合家大笑,让一个男孩的成长烦恼变得美丽、自然,以及自由。母子越界之后,妈妈那段话诠释了一切:“我不要你为这件事感到不开心,羞耻或后悔,我们要以此作为很美的、庄严的一瞬间留在记忆中。但它永远不会再发生。没什么,我们再也不会提起,这是我们间的秘密。我会毫无责任地体贴地记住它,答应我,你也会这么做。 ”坦然面对这个世界的一切现象,它们很奇妙,也都很正常。孩子正处青春期的父母,都该认真地读一下这部电影。

难得在法国新浪潮电影中看到惊喜。对成长主题最锋利的解构,母子乱伦,重新审视道德与自由,强大到用一哄笑声泯灭众生之惊愕。

难得在法国新浪潮电影中看到惊喜。对成长主题最锋利的解构,母子乱伦,重新审视道德与自由,强大到用一哄笑声泯灭众生之惊愕。

6 ) 为什么爱因斯坦说,没有好奇心等于行尸走肉?

文章来自公众号:任游子

爱因斯坦说:“谁要是不再有好奇心也不再有惊讶的感觉,谁就无异于行尸走肉,其眼睛是迷糊不清的。”

爱因斯坦通过这句极具形象的话语凸显了好奇心在人生旅途中有多多么重要。

在历史上,很多对人类做出卓越贡献的人都有关于好奇心的小故事。

牛顿对一个苹果产生好奇,从而发现了万有引力。伽利略看吊灯摇晃,好奇发现了单摆。瓦特对烧水壶上冒出的蒸汽好奇,改良了蒸汽机。

我国铁路之父詹天佑,从小就喜欢各种关于机械的玩具。有时,他把家里的钟拆下,研究它是怎么转动和报时的。玩具成为他对机械的兴趣入门。最终,他成为我国著名的铁路工程师,建造了当时洋人也无能力建设的京张铁路。

关于名人与好奇心的故事数不胜数,我不妨来讲一个自己关于好奇心的故事。

当初,我刚搬到某个小区。每天下班后,我就在小区附近寻找从未听或从未品尝的美食。历经一个月的“挑食”,我成功地掌握了小区附近各种特色小吃的地址。

有次,好友刚来西安,为表地主之谊,我每天不重样地带他吃各种美食。一周后,朋友惊讶地问我:“我的天啊,你就想一张特色美食的活地图啊!”

我听了他的赞扬,内心尤为自豪。这一切都来自对特色美食的好奇心。

这时,你就会明白吃货和减肥的鱼和熊掌不可兼得的滋味。

创造的动力来源于好奇心。有了对某种事物的好奇心,便有了源源不断的动力。我要“拆卸组装”,一探究竟。因而,随着对这件事物的了解加深,量变达到质变,将很有可能创造一种新的事物。

好奇心对于人类而言,分为两种,我们分别称为红色性格和蓝色性格。

红色性格的人对各类事情都充满好奇,看到每种产品都想尝试体验,探索其中的奥秘。但是,由于好奇心的宽泛,当他们体验某种产品遇到难度时,很可能就选择放弃,寻找另外可以满足自己好奇心的事物。宽泛而浅薄,这就是红色性格的特征。

蓝色性格的人天生具有专注的优势,当他们对某种产品产生兴趣时,就会一发不可收拾,少则一天,多则十年,非要探究清晰这个产品的功能、材质、原理等,这种好奇心导致的持久探索,蓝色性格的人很容易成为某个领域的专家。狭窄而深邃,这就是蓝色性格的特征。

一般情况下,好奇心的浓厚程度伴随年龄的增长而减少,年龄越大,了解的事情越多,好奇的事情自然减少。所以,年龄越大的人,越缺少活力和创造。

那么,如何规避这种情况呢?

在艺术领域,比如导演和演员,他们每参演一部戏,就等于体验了一种人生,演技也愈发高超。对于一个优质的演员来说,每一部戏都能激发好奇心。这也是很多老演员说要演到老的内在动力。

对于普通大众而言,我们不能像演员一样,提高技能的同时,又体验不同的人生或事物。但我们可以向演员学习,以某一事业为人生主线,确保生存状况良好的前提下,大胆去探索不同的行业。

举例而言,达芬奇,以绘画为主业,但他同时也是天文学家、发明家、建筑学家,还擅长雕刻、音乐、地质等20多个领域。苏东坡是顶级词作家,也是书法家、大画家,皇帝秘书、佛教徒、修道者、慈善家、工程师、发明家。

我们可以称达芬奇和苏东坡是跨界能手。他们的一生因好奇心的彰显,而充满趣味,让人艳羡不已。

这时,反观以公务员等稳定职业自豪的朋友,他们的工作其实琐碎重复又无所事事,这样的一生本身就是悲剧,如同爱因斯坦说的行尸走肉。

你愿意做个庸碌一生的公务员还是对世界充满好奇想要探索的人呢?

爱因斯坦说:“谁要是不再有好奇心也不再有惊讶的感觉,谁就无异于行尸走肉,其眼睛是迷糊不清的。”

爱因斯坦通过这句极具形象的话语凸显了好奇心在人生旅途中有多多么重要。

在历史上,很多对人类做出卓越贡献的人都有关于好奇心的小故事。

牛顿对一个苹果产生好奇,从而发现了万有引力。伽利略看吊灯摇晃,好奇发现了单摆。瓦特对烧水壶上冒出的蒸汽好奇,改良了蒸汽机。

我国铁路之父詹天佑,从小就喜欢各种关于机械的玩具。有时,他把家里的钟拆下,研究它是怎么转动和报时的。玩具成为他对机械的兴趣入门。最终,他成为我国著名的铁路工程师,建造了当时洋人也无能力建设的京张铁路。

关于名人与好奇心的故事数不胜数,我不妨来讲一个自己关于好奇心的故事。

当初,我刚搬到某个小区。每天下班后,我就在小区附近寻找从未听或从未品尝的美食。历经一个月的“挑食”,我成功地掌握了小区附近各种特色小吃的地址。

有次,好友刚来西安,为表地主之谊,我每天不重样地带他吃各种美食。一周后,朋友惊讶地问我:“我的天啊,你就想一张特色美食的活地图啊!”

我听了他的赞扬,内心尤为自豪。这一切都来自对特色美食的好奇心。

这时,你就会明白吃货和减肥的鱼和熊掌不可兼得的滋味。

创造的动力来源于好奇心。有了对某种事物的好奇心,便有了源源不断的动力。我要“拆卸组装”,一探究竟。因而,随着对这件事物的了解加深,量变达到质变,将很有可能创造一种新的事物。

好奇心对于人类而言,分为两种,我们分别称为红色性格和蓝色性格。

红色性格的人对各类事情都充满好奇,看到每种产品都想尝试体验,探索其中的奥秘。但是,由于好奇心的宽泛,当他们体验某种产品遇到难度时,很可能就选择放弃,寻找另外可以满足自己好奇心的事物。宽泛而浅薄,这就是红色性格的特征。

蓝色性格的人天生具有专注的优势,当他们对某种产品产生兴趣时,就会一发不可收拾,少则一天,多则十年,非要探究清晰这个产品的功能、材质、原理等,这种好奇心导致的持久探索,蓝色性格的人很容易成为某个领域的专家。狭窄而深邃,这就是蓝色性格的特征。

一般情况下,好奇心的浓厚程度伴随年龄的增长而减少,年龄越大,了解的事情越多,好奇的事情自然减少。所以,年龄越大的人,越缺少活力和创造。

那么,如何规避这种情况呢?

在艺术领域,比如导演和演员,他们每参演一部戏,就等于体验了一种人生,演技也愈发高超。对于一个优质的演员来说,每一部戏都能激发好奇心。这也是很多老演员说要演到老的内在动力。

对于普通大众而言,我们不能像演员一样,提高技能的同时,又体验不同的人生或事物。但我们可以向演员学习,以某一事业为人生主线,确保生存状况良好的前提下,大胆去探索不同的行业。

举例而言,达芬奇,以绘画为主业,但他同时也是天文学家、发明家、建筑学家,还擅长雕刻、音乐、地质等20多个领域。苏东坡是顶级词作家,也是书法家、大画家,皇帝秘书、佛教徒、修道者、慈善家、工程师、发明家。

我们可以称达芬奇和苏东坡是跨界能手。他们的一生因好奇心的彰显,而充满趣味,让人艳羡不已。

这时,反观以公务员等稳定职业自豪的朋友,他们的工作其实琐碎重复又无所事事,这样的一生本身就是悲剧,如同爱因斯坦说的行尸走肉。

你愿意做个庸碌一生的公务员还是对世界充满好奇想要探索的人呢?

告别了懵懂的孩童时期,孩童世界不复存在,同时又尚未建立起成年人的世界观,对自己的未来充满好奇心。与二战时期的世界相对应。路易马勒把母子之爱拍得干净纯洁,没有一丝低级淫秽,是少年成长间庄重而体贴且值得铭记的一瞬。O娘的故事。加缪。印度支那。爵士乐。死亡。路易马勒惊人的掌控力。

没有想象中那般晦涩 相当通俗 而且影片还探讨了死亡 战争 殖民地 宗教等一系列问题 虽然是讲乱伦的故事 却拍的丝毫没有羞耻感 就像主角的母亲说的 “不需要为这件事感到羞耻或后悔 这是一段记忆中很美很庄严的回忆 但它永远不会再发生”

法国人确实有这个本事,把一切伦常中不正常的东西演绎得非常正常。

法国人的电影看上去总比他们的人显得深刻、复杂……没什么他们不敢拍的,这片子把躁动的青春拍的非常到位,非常,还是深刻……不知道路易斯·马勒算不算新浪潮导演

“我可以建议您把他当成年人对待吗?”“-这是母亲与儿子间怎样的谈话啊!-我也是你的朋友。”正是母亲和家人将罗伦特当成一个成年人对待,认为他能做成约定的承诺,才在母亲与罗伦特做出越界的行为后以一种令人惊异的宽容方式看待已经发生的事,片尾一家人狂笑不止更是突出这一“另类”的成长环境。

很敏感的题材,被导演处理的清新自然,对少年心理变化的掌握游刃有余。

成长的复杂滋味。能在政治环境、阶级讽刺与微妙的母子关系中游刃有余,培养出一种震撼而又令人惆怅的多重情绪,马勒对度的把握实在精妙。

想到导演还拍过一部《雏妓》,厉害。放到现在不就是那个什么几号房间了。

Malle loves to deliver shock value. But in this case the movie is not so much about incest as about adolescent sexual confusion. Worthy.

路易·马勒第11作,也是首部他本人编剧的剧情长片。青春的迷惘骚动与俄狄浦斯阶段的超越。街头撞见母亲与情人段契如[四百击]变奏。三兄弟比较JJ尺寸。菠菜网球(以盘为拍)及红土欢闹比赛。乱伦戏拍得轻松而浪漫,一如母亲无拘无束的洒脱性情。向姑娘求爱失败,转战隔间,翌早全家大笑,妙绝。(8.5/10)

好直白的青春期骚动。打破禁忌,迅速成长,大概每个男人都从恋母开始,这没什么,反而有些美好。这么年轻的妈妈有三个这么大的儿子好帅气呦!

法国资产阶级出身就读于宗教学校的叛逆少年成长史:反殖民反战(印度支那募捐)、反宗教(戏谑恋童gay神父、嫖妓)、反阶级反资本(爱爵士和车赛,亲近工人阶级,嘲讽保皇党资本家后裔是纳粹)、反伦常(尊重母亲外遇,俄狄浦斯情结,蔑视女性伪贞洁)。罗伦特最终打破所有规则,解除束缚与自我和解。

一个宇宙熊孩子躁动怀春成长的故事。。。而且这个故事并不怎么光彩。。。而且发春的对象还是他妈妈。。。。

两个哥哥才是奇葩。

我有時覺得自己還停留在“口腔粘著期”...............p.s.Charlie Parker就是Louis Malle!——“我討厭爵士樂”就是沙文主義泛濫的法國人後來對赴美發展的Louis Malle的集體审判!

复杂大环境下的微妙家庭关系

一些年少时的尴尬记忆。

【且看浪漫之都,青少年如何面对性成长。】有着“教室别恋”的少年懵懂和渴望,夹杂着政治大环境下的微妙家庭关系,还有着“西西里美丽传说”的家庭政治因素。结局一家人哈哈大笑,不知道的幻想着那晚,知情者仿若昨晚事情没有过,一切都很美好,只是情节上有些拖沓。

战后法国 色彩新浪潮 听着大鸟爵士乐打飞机 青春性觉醒 菠菜网球 性感的母亲 愚蠢的教会 路易马勒对颜色的控制真的杰出

8/10。重温。散发着马勒对资产阶级的猛烈触犯:兄长都是坏榜样,他们带着罗伦特早一步跨入成人世界,体验抽烟、喝酒、嫖娼的陋习,而神父对男童的隐藏欲望(把双手放在告解的男童大腿上),罗伦特对跳舞姐妹是女同性恋的调侃以及母子在夜晚派对后屈服于通奸诱惑的偶然性,生动而活泼的嘲讽了宗教价值。