详细剧情

长篇影评

1 ) 跳出家庭与信仰而聚集反战的女人

《我们去哪儿》这个故事以中东地区宗教冲突为背景,虚构了一个信息半封闭的小镇,镇上的男人们受到外界宗教冲突的影响,穆斯林信徒和基督教信徒经常大打出手,还手持枪械。镇里的女性,作为完全不参与外事的穆斯林女性,只能眼睁睁看着自己的儿子或丈夫在冲突中丧生。最终无法忍受生离死别的女人们团结起来,通过一场场啼笑皆非的暗中行动来平息冲突。

电影的开场和结尾画面是严谨的前后呼应式——葬礼、穿黑衣服的女人、哀歌、形体舞台剧化的表演,带来强烈的视觉冲击外,还有听觉的并行,导演纳迪·拉巴基再次植入了法式舞台浪漫戏剧的演出手法,然而却弱化了主题的表达效果,于是不得不通过旁白这种最明显的解说手法来增强因女性浪漫而牺牲的戏剧主题突出点。

在故事情节上,纳迪·拉巴基是个非常会讲故事的女人,她的头脑绝对是法国女人那种浪漫之下思维逻辑连贯强势派的,每一个情节的扣接转折都会早早埋下牵引的线索,就像是那种与人交谈中早就把整个谈话走向和内容都设计好,对方无论说什么都最终要将谈话结果引向自己所要的结局之中。片中基督教男孩之死到被人发现因而引发整个小镇再次点燃宗教冲突这个桥段,是导演兼编剧的纳迪·拉巴基最缜密一笔,且非常具有故事性戏剧性,将整个故事推向高潮。

用自己的性别和身份写故事,别说做电影,除了特殊职业,在现在强调平等和无性别差距的情况下,很容易让人反感生疑。故事中,导演纳迪·拉巴基把男人全部塑造成好战分子,他们的角色定位统一是“勇猛、好战”,就算是前一秒刚和美艳绝伦的女人跳舞喝酒,后一秒可以为了男人间一点不和言语持枪群斗,而女性,片中所有的女人,角色定位统一是“善良的母亲、唯唯诺诺的妻子和沉默寡言的女儿”,她们在日夜的宗教争端中因亲人离散而不顾一切反战反争斗。这种大规模的性别介入定位角色,有点过度戏剧化,这个问题在其另一部作品《焦糖》中更为突出。然而对于此质疑,纳迪·拉巴基说:“用自己的身份和性别来写作和拍电影,我觉得这是一件很可靠的事情,因为对于作者而言,说出自己的话是最重要的。如果我写了一个男性的故事,那么我可能会觉得那就是一桩任务和作业,未必会做得这么透彻。”

一个出生在阿拉伯世界的女性,却在事业和人生中不仅不叹息自己的性别,反倒不在乎运用好自己的性别理解力去完成和成就自己的事业及人生,这是极具莎乐美式的自信和独特。

同时,鉴于导演每次在电影中探讨的话题都大涉世界,而非小情小爱,也不得不就戏剧化导演过度性别介入角色定位的问题。知己知彼的对待自己和所要讲好的话题观点,这个从自身切入来说感受会更真实更容易打动人心。因为对于生命,对于战争,我们不可能想对于小情小爱那样有万花筒看世界的千奇百感,和平和冲突一直是最终反复的动向。

论电影中极具浪漫手法的歌舞音乐和喜剧桥段,确实带入了女性柔美的特色而淡化了冲突,比起用真个篇幅用大手笔特技烟火来营造的战争,这种反战题材有些弱势,却一直顺笔于导演植入角色定位的关键性——女性,不是在墨西哥战争中出来的女游击队,而是以妻子和女儿母亲角度来柔情化解冲突的感受,她们渴望家庭完整的悲伤以柔克刚地穿破冲突和武力,至于歌舞,其实如果这不是一部反战题材电影,它真的可以媲美巴黎大剧院里的歌舞剧或者宝莱坞的香艳歌舞,喜剧的剧情也十分能调侃刻画出小镇里朴实生活画面,没有比喜剧更适合乡村,这个可参考东北二人转!

纳迪是个非常懂得用自身所长或特色来谋划人生的女性,与其说谋划,她那浪漫主义手笔又光彩熠熠夺人眼目。比起探讨哲学或雕塑的法国女人莎乐美,纳迪却又将这份自信和夺人眼目的浪漫运用到了人文关怀里,这与她的出生有关。

片尾最后一幕“我们现在去哪”,棺木因宗教冲突导致不知葬于何处的提问,神来一笔地结束了全片,留下了“我们是谁,我们来自哪,我们要去哪”的哲学探讨,这部全片女性构建画面感的电影又仿佛将高更的画作呈现眼前——“我们现在去哪儿?”

宗教信仰也挽救不了的人类战争与冲突,最终归于人性的自我探索和思考,万念粉扎皆因欲念而起。为情感介入进而反思人性反思冲突这一新而现存的角度,细腻真挚的感动而鼓掌。为自身同为女性却无力所为而绝望。

2 ) Against the "Fusha"s

Unity and coexistence are often easier to pronounce than to actually practice. That was the case in Where do we go now? – in which a village nothing but mundane – but with the exception that Muslims and Christians are cohabiting in the same village. Their coexistence, however, are under increasing strain as sectarian conflicts seep into their daily lives, enraging the males in the village.

Sectarian conflict would be one of the most common themes presented in this movie: Indeed, the fist fights, the gun shots, and the screaming all forebode the coming of violence. And this is definitely not the first time that this sort of violence erupted. When a village was surrounded by barbed wires and landmines, with residents getting killed in conflict, we could almost imagine an almost identical past where the fate of this small village was inevitably linked to a larger history.

The barbed wires and landmines form a powerful symbolism on multiple levels – it first, as previously mentioned, signifies previous existence of violence, conflict, and death, but at the same time underwrites the village’s isolation. How did those barbed wires get placed? Don’t they have an isolating effect for the village from the outside world? It leaves much room for speculation, that maybe the reason that Muslims and Christians were able to coexist was the existence of those wires. But ultimately, even the most insurmountable physical barrier succumbed in front of modern technology, which delivered news of those conflicts to the male residents. The theme of technology’s role is worth contemplation – whether their existences fueled sectarian and other types of conflicts? Isn’t it that we’re living in a conflict-ridden world now?

But maybe technology both matters and does not matter. With motivations, be it sectarian or other reasons, people would find ways for violence. If it’s not guns, then knives. It seemed that just as the characters in the film continuously mentioned, they are already cursed. Religious leaders in this film do not play an important role in this film because they’re powerless to rein in their adherents, which would be weird when you think about the supposed role of those leaders. Maybe it’s not because of religious differences that people resort to violence, but a simple us-them mentality made religion an easy scapegoat and fanned violence and contention. When the Father told the Imam “Dear Imam, forgive them, as they don’t know what they’re doing,” it led me questioning why people always attribute religions as the root cause for violence, but not something inherent in us.

And maybe we should reflect on our behaviors in light of that. When the head of the village ceremoniously announced the opening of TV, he used MSA and celebrated how unity could overcome divide, and the lofty ideal of unity and coexistence. But when the test arrived, did he stand up to it? Maybe we should stop those empty talks of ideals, dreams – all unrealistic and would ultimately prove disappointing – and actually focus on human beings – as did the women in this movie. They’re the heroes.

The rich symbolisms in this film are especially impressive. The beginning of the film shows several footages – both Muslim and Christian women cleaning the final resting place of their families, the barbed wires and the minefields. These gradually start to make sense as the movie progresses, and, upon reflection, convey great meaning. The graveyard is an especially potent one, when the Ukranian dancers remarked “even dead, they’re divided.” And when they ultimately Nassim, the question “Where do we go now?” put another layer of emphasis on this piece of land. The question not only indicates a dilemma, but most importantly, may show the uncreativeness when people deal with these issues.

“Where do we go from now?” The question got me thinking. If they’re only going away from this crisis, but not finding a real, creative path, maybe the tragedy would re-enact themselves again in this One Hundred Years of Solitude-like piece of land.

3 ) 小村女人

一个只有一条路通向外界、几乎与世隔绝的小村庄。借助两个年轻人把村子东西卖出去再买回各家所需物品。四周埋着地雷,偶尔会炸死乱跑的羊,像村长说的:这只羊牺牲自己,挽救了一条人命。

村子生活着两个教派的人:穆斯林和基督徒。从临近结尾几名女人挖出早先藏匿的枪支,我更愿意相信他们的亲人是在外面因为教派冲突而死,而不是在村子里。

女人们珍惜小村的和睦。而男人们则很容易因为一件事冲突,就像拉货青年不小心弄折了基督徒的十字架,接着就是清真寺被赶进一群家禽牲畜。更在另一拉货青年在外面被乱枪打死后几欲引发灾难后果。从隐忍的母亲那里得以体现出来,为了阻止灾难,甚至不惜开枪打伤剩余的儿子,只是不想让他也死掉。

对此,女人们想尽诸多办法:电视播放时政新闻时故意吵架,请回了外面的舞女团,借助大麻,最后甚至改信对方教派。这个过程是有趣的,欢笑后面隐藏的也是女人的无奈,就像寡妇对着在自家点打架的一群男人们喊:难道我们女人天生是为你们这些男人哀悼的么?

在某评论中经提示:寡妇的扮演者也是本片导演。早先还真忽略了这一点。

---------------------------------------

一句话评论

纳迪·拉巴基在这部电影里提供了一种“消解战争”的方法。毫无疑问,她是真诚而且真挚的。影片中的人物也一样纯洁而美好。这种解决矛盾的途径比任何一种老奸巨猾的解决办法都要行之有效。

——好莱坞报道者

幕后制作

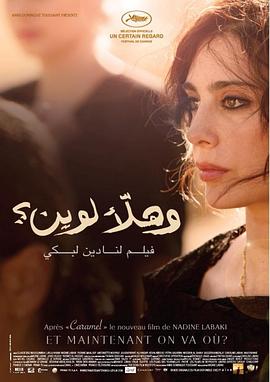

影片入围了2011年戛纳电影节的一种关注单元,并代表黎巴嫩报名参加2012年奥斯卡最佳外语片的角逐。它的故事实实在在地发生过,那是在一个孤立的小山村里,几个不同信仰的妇女,因为不忍心看到人类因为宗教的原因相互残杀而自我牺牲,以唤醒自己男性亲人的良知。虽然有现实的故事打底,但是让纳迪·拉巴基拍摄这部电影的契机并不是这个故事,而是她的的孩子。2008年5月7日,纳迪·拉巴基一边在考虑是不是要个孩子,一边在考虑自己的新片。也是在那一天,贝鲁特发生了大规模的冲突,道路封锁、宵禁和航空管制又一次降临到了这个国家。于是,纳迪·拉巴基便在思量,如何才能让自己的后代免于愚蠢的因为毫无必要的缘由自相残杀。

有人觉得影片涉及到了战争,可是纳迪·拉巴基却觉得恰恰相反。她说:“这部电影是讲述如何避免战争的。在黎巴嫩生活,你一定就能体会到什么叫做生活在恐惧之中。所以怎么样离开这种生活才是必须要考虑的。战争是人类荒谬的举动,所以,让不同信仰的人聚集在一起反战,谈不上是天方夜谭。因为我是女性,所以很能理解女性的感受。所以在《焦糖》和这部电影中使用女性作为主角,能更加清楚地表达出我的思想。因为用自己的身份和性别来写作和拍电影,我觉得这是一件很可靠的事情,因为对于作者而言,说出自己的话是最重要的。如果我写了一个男性的故事,那么我可能会觉得那就是一桩任务和作业,未必会做得这么透彻。”

4 ) 吾等何处去

2、影片叙述的主题并不新鲜,以黎巴嫩及周边地区基督徒与穆斯林的冲突为背景的电影有很多,尤以去年的差一步在“奥外”中登顶的《焦土之城》水准最为突出。可以说《焦土之城》已经将宗教冲突及战争对大众的伤害表现到了撕心裂肺的地步了。没想到,《吾等何处去》选择的叙事视角仍旧新意十足,讲述的故事具备很强的可看性。

3、整体看,美女导演(真的很美)纳迪.拉巴基很擅长讲述这种表象轻松、内涵深刻的电影,整部电影的走向一直掌控在导演的手中,不徐不缓的讲述了一个略显理想化的故事。

4、说它略显理想化是因为我真的十分怀疑现实中是否真的会发生电影中的故事。当然,我真心希望电影是真实事件改编。不过,去年看过《焦土之城》后,我曾经很认真的查阅了黎巴嫩国内宗教冲突的资料。据资料显示,现实中黎巴嫩国内基督徒与穆斯林的冲突之烈、矛盾之深实已到了不可调和的地步,且维持了数十年之久,两个教派信徒的仇恨程度远远超过了我们的想象。从这个角度看,《吾等何处去》中那些可爱可敬的妇女真的不大可能在宗教冲突紧张的地区出现,可能电影想表达的是导演的一种愿望。当然,这也是我们大家希望的。

5、本是同根生,相煎何太急。毕竟任何一种主流教派的本质都是教人向善的,我们真心希望各种信仰的人们都能够和平友善的生活在同一个世界上。

6、影片中那些欢快的音乐节奏活泼,很是好听。

ps:哇!原来居然还真是真实事件改编!!!实在是......太好了!!!

5 ) 谁在庇护谁?

村里的人来自不同家庭,拥有不同信仰,男人们总是分党结对,远没有那一群妇女来的团结。但无论男人,女人,塔克拉的杂货店和艾玛的咖啡馆都是每天要去的地方。在这个两个小空间,让男人们走得越来越远,而女人们也因此格外团结。外界的耳濡目染和内部的小矛盾很快也让男人们站在了对立面,冲突一触即发。

女人们为此想了各种荒谬而可笑的方式——冒充圣母显灵、邀请乌克兰舞女。可这一切并没有让男人们的关系得到改善,反而更加恶化。而纳西姆的死也为女人们提供了一个契机。可悲的是他的死亡并没有由小乡村日渐加深的宗教冲突所导致的。而是借此告诉观众,在这个与世隔绝的村庄之外,每天有各种持枪或者更严重的暴力冲突在轮番上演。如果村民继续愚昧下去,终有一天会酿成同样的悲剧。

这塔克拉第一次怀疑起她所信仰的神灵,这个悲伤愤怒的女人质问圣母为什么没有保护好自己的儿子。也是从这一刻开始她彻底抛弃了原来的信念,在她的世界里有一种东西坍塌了。所以才有了最后的大反攻,女人们似乎终于赢得了一次胜利。(对这个部分的强调让另一个《人妻冲冲冲》的译名更为贴切。)

当最后抬着棺木不知所措的男人喊出“WHERE DO WE GO”时,一切显得无比可笑。或许冲突在这个小山村会消失,但我并不认为这群愚蠢的男人真正了解了妻子们的用心。

6 ) 非常一般嘛

整片一句话就能归纳下来:还是妇女同志觉悟高。当然如果妇女同志们真的有如影片所描述的影响力的话,国际关系理论界早就被女性主义国际关系理论一统天下了吧。

虽如此,本片还是有值得夸奖的地方的。幽默的地方还真是颇自然不造作。女主某些个角度看还是不错的。

想要渴望和平~就得破除宗教!

沉重并轻松着 更多的是欢乐和几个穆斯林老太太的可爱。

小鸟 给我传递个爱的信息

砰的一声枪响,隐忍的母亲塔克拉打断的不只是自己唯一剩下的儿子的腿,更是打响了这群女人们反战的号角。

真好

让我想起了很多年前写过的《曲解贺拉斯之誓》

有点小惊艳。

Nadine Labaki自編自導自演的。電影如同她的臉也如同那支動聽的插曲一樣譲人过目难忘。

导演用幽默笑料,欢快歌舞和夸张的戏剧冲突来处理这个严肃的宗教冲突问题,的确很出色,让观众在大笑之后仍深陷沉重的悲剧气氛和思考中,配乐和摄影都太美了。

想看[2011-12-14],终于趁着戛纳补课看完了。概念先行且几乎只有政治宣传般的生硬故事也是……但是拍得实在太好玩了,减轻了不少嫌恶感。最后迷幻趴体加宗教互换的梗简直笑尿了,生生拉回及格线。歌舞段落虽尬得要死,但是用法(尤其剪辑和时间观念上)比较值得一说。

重看,早就探讨过剩的宗教冲突,在举重若轻的喜剧感演绎之下,焕发出了新的光彩,面对即将到来的腥风血雨,勇敢迈步守护危巢,以优雅姿态面对残忍,如同手握玫瑰迎击枪炮,用无声的嘲讽给这个暴戾无趣的世界最温柔的一击。拉巴基无论生活流铺垫还是法式幽默全都信手拈来,非常有才。

力作,和平就这样被女人创造了。

看完猜这个导演是个水瓶座,这么严肃的题材(异宗互戕)还玩幽默还歌舞,然后发现导演就是那个漂亮女主演。她以刻板的性别印象为基础释放了一种近乎幼稚的和平(幼稚总是内在于理想主义),但提出的是真问题:一个丧子的母亲和圣母对峙,人类如何与敌人共处,文明的坚硬也许就在那点母性的不忍里。

怎样做到艺术性和娱乐性并重?这部电影给出了答案。放映之后的问答环节有一个有趣的知识点: 这部电影在黎巴嫩的票房为史上第三,仅次于大船和蓝色外星人。

她们在最荒诞的现实面前做到了最极致的优雅,在善的光辉中,她们才是这土地上赤脚行走的神。

媽媽老婆站起來!! 結局的殺手鐧實在始料未及,雖然議題是沉重的,戲中卻不時出現幽默與歌舞來詮釋,非常地合拍。這些婆婆媽媽大部分都是從路上找來的素人演員,但交出了一場場精采的好戲阿!

为了避免被冲动蒙蔽的男人们陷入愚蠢而无谓的战争,善良而聪明的女人们绞尽脑汁啊

影片用一种轻快的方式去解决宗教之间的冲突问题,尽管不那么实际,却让人在内心悲痛过后给人希望。女导演视角下的女性电影,时而欢快,时而悲伤,时而温情,让人忘记沉重的现实~

只有电影才会这样吧,在复杂的宗教信仰民族等冲突问题上都能化解的那么天真,也许是女导演的缘故,骨子里善良的像少了根筋。影片在形式上的杂糅上虽让电影更具观赏性了,但依旧只是浮于表面的形式,很有趣也很杂乱,就像印度神婆上身的歌舞,本来沉重的现实也跟着变成童话般的超现实了。★★★

有的时候信仰可以毁灭世界,而拯救它的,是妇人之仁。 PS:编+导+演的纳迪.拉巴基真是个才女!