详细剧情

长篇影评

1 ) 男主角太装B了,一切都不在掌控中

装B装大了,复合约翰·屈伏塔一贯的角色设定。

2 ) 属于帕尔玛的「元电影」

「元电影」,个人理解为“关于电影的电影”,又或者说是“关于电影幕后制作过程的电影”。

《凶线》从一开场就为观众奉献出两段代入感极强的第一人称长镜头:

这段炫技十足的开场已经成功将观众的注意力吸引,并在潜移默化中帮助观众建立起接下来的观影预期。而正当观众带着预期去观看接下来的故事时,一个无比糟糕的尖叫声把这一切彻底摧毁。而后镜头一转,我们才知晓刚刚的画面仅仅只是一部B级片的拍摄素材,而银幕前的制作人员正为这一糟糕的音效苦恼。

但也正是这个“顽皮”的音效设计,使得观众终于发现这段调度精湛的开场其实是一个经过精心包装的“影中影”结构。并且这段开场还正式确立了影片的故事母题与声音设计母题,也展现出帕尔玛在「元电影」这方面的切入角度:影像中「画面」与「声音」的引导/对立关系,同时也是关于电影作为媒介所能触及到的感官路径的探讨。

一、裂焦镜头、背面投影与分屏

裂焦镜头,即通过特制的“裂焦屈光镜”来造成一种类似深焦大景深的效果,在视觉上能够使得近景与远景两个平面的物体成像都十分清晰。而另一个显著特征便是在两个正焦平面的过渡地带会失焦,即景深不连续。该手法最早出现在《公民凯恩》之中(摄影师是格莱格·托兰德),而在帕尔玛手中被发扬光大,变成了最佳的叙事辅助手段。

很多时候我们观看对话戏,除了正反打以外,还可以通过变焦来切换讲述者与倾听者,有助于观众的视线聚焦于叙述主题。但帕尔玛很多时候偏不这么干,要么他将对话中的两者聚焦于同一视觉平面,要么会添加其他未参与对话的客体,当两者同样清晰时,传统的聚焦手段便被割裂,从而创造出全新的戏剧效果。

而在其他非对话戏的段落里,当裂焦镜头取代变焦镜头后,那种自然的视线引导手段便消失殆尽,用最粗暴直白的方式将信息展现给观众。另一方面,裂焦镜头中被摄制对象的近景远景位置关系也是解读帕尔玛镜头序列的重要线索。当人物处于远景,物件处于近景时,则是在无形中为镜头增添一层「窥视」的效果(第一人称视角下该镜头效果最为突出);而人物处于近景,物件处于远景时,则是直观的指明角色接下来所要做出的选择,亦或是对角色自身命运的最佳暗喻。

背面投影,一种将前景动作与事前已在摄影棚拍摄好的背景胶片投射到摄影中的银幕上,再经由摄影统合在同一底片上的技巧,与正面投影相对。由于早期拍摄外景时会受限于摄影机和录音技术,背面投影被广泛运用于拍摄行驶车辆中人物的对话镜头。而希区柯克也擅长利用背面投影去扩展电影里的世界,并达到追求“自然主义”的目的。尽管随着技术的不断更新,这种技术本身也已经变得十分不自然。那么现在仍然使用背面投影技术肯定是出于某种艺术上的考量,通过这种前后景不协调所造成的空间割裂来让观众回想起古典好莱坞的风格。

其实仔细回看《凶线》,帕尔玛也仅仅是在两处地方运用了背面投影:一处是男主通过录音推导出事故现场的真相;另一处便是男主飙车追赶的段落。前者毫无疑问是符合我之前所说的“艺术考量”的,而后者呢?在这个实景拍摄追车戏已无限制的时代下,帕尔玛为何要选择这种“吃力不讨好”的拍摄技法?是单纯的怀旧,还是另一种形式的“艺术追求”?

分屏镜头,正如字面意思那般,是将银幕上完整的画面分割成不同的几个画面,从而达成美学上或者叙事上的特定需求,原本是电影语法上的的某种形式,最初却是起源于电影早期的技术发展,例如 遮片技术、多重曝光技术等。早期电影对分割画面的尝试可以被看作是 一种对技术手段的试水和画面空间的扩充 ,而进入六七十年代之后的电影,则是真正将分割画面纳入到电影叙事语法的体系中来。这其中最具代表性的就是帕尔玛。

但注意,尽管帕尔玛是分屏手法的大师级人物,但他在运用该手法时却显得非常克制,一部电影只用一两次,这样能最大限度的保证观众对单一手法的新鲜感。在帕尔玛手中,分屏技术打破了时间和空间的界限,在有限、固定且单一性的银幕空间上,呈现了多种空间和多种时间的进程的组合。在某些时刻,两个分裂的叙事空间会在高潮处汇聚到了一起,但分屏画面却依然在持续,取代了传统的正反打手法,空间以一种多视角的表现形式出现在我们面前,并具备了并置的时间特征。通过这种表达,帕尔玛的分屏技术创造出了一种全新的悬疑:传统的剪辑手法像是对观众的提示,造就悬疑的同时也毁掉了悬疑。而分屏技法规避了这一点,通过引入不同的视角,将所有元素都放到画面中来。在这样的时空并置中,人物构成了一种共存性的平等关系。或者是同一人物所进行的活动,但是呈现出来的信息却能更加全方位。对观众来说,这种“麦格芬”既存在又不存在,始于对希区柯克的致敬,但又比希区柯克更加丰满。

但与帕尔玛的其他分屏不同,《凶线》里的唯一的分屏段落并未承载悬疑要素,在形式和内容上也意外的“单调”。这一段落首先是由一个交代景别关系的裂焦镜头开始(某种程度上也算暗示了裂焦镜头和分屏的内核上是趋近的),左边是详细的电影音效整理工作,而右边只是一则关于州长出席烟火晚会的新闻。在剪辑点的数量上,左边明显是要比右边多的,这样就方便集中观众的注意力到左半画面内。而音效上也暗含后续故事发展的线索(“foot steps”“clock”“thunder”“shot”“body fall”等具体音效),画面更是直观的展现了电影后期制作的内容,与右边的新闻媒体进行对比,一方面是再度切题「元电影」的属性所在,另一方面也稍稍涉及到了媒介自反的内容(从角色对新闻毫不关心的态度也能佐证,亦或是「电影」对「电视」的媒介对抗?)。

二、电影是「视觉」与「听觉」共同整合的艺术

关于电影本身,从首部有声电影《爵士歌手》上映以来,电影就不再仅仅只是纯视觉艺术了。而至于声音如何与画面产生关联,这其中也要遵循某种基本规则。1959年布列松所拍摄的《扒手》也许就是这一规则最典型的案例:在没有人物/人物还未入场的空镜头内,音效可以提前铺垫情绪、传递信号、构建空间。也就是“先声,后视,再感”。让声音去引导观众,促使他们对接下来的画面产生某种预期,而创作者接下来要考虑的,是顺从预期亦或是违背预期,则取决于他们所想要达到的戏剧效果。

先让我们来看看电影9-12分钟这一段男主录制环境音的片段。基本完美沿用了上面讲过的声音引导理念,主角手中跟随声音游走的麦克风便是「由声入画」的过渡物件。在这一段落中,声音和画面仍然是耦合的。除此之外,帕尔玛还安排了五组相似的镜头序列,来引导观众一步步走向剧情的爆发点:

第一组镜头序列:三个镜头由近及远,一步步放大环境缩小人物,并在最后一个镜头内通过前景虚化的树叶来强调某种无形的窥视感,也在暗示危机/事故的到来。

第二组镜头序列:依旧是由近及远的镜头安排,不过这一次是从“被窥视者”的视角为主,继续填充环境,并在最后用裂焦镜头来丰富影像的趣味性。

第三组镜头序列:无特殊变化,仅有过渡作用。

第四组镜头序列:镜头安排仍然无特殊变化,但最后一个镜头再一次出现了前景虚化的树叶,强化窥视感,可以看作危险信号,事故即将发生。

第五组镜头序列:没有使用之前的镜头过渡模式,而是直接切入录音人和声源的裂焦镜头,明示二者之间的符号象征关联,也为后面主角追查真相的行为作视觉铺垫。随后,车祸发生,该段落结束。

在这一段中帕尔玛尽情展现了自己的调度功底,通过镜头序列中不同的细节变动来暗示危机/事故的发生,而且每一组镜头序列中音效都是至关重要的部分,每一组镜头序列的承接都是由音效带动镜头运动,然后再由镜头运动将视线自然引导至目标。

但在此之后,电影剧情上的「视」与「听」被刻意分割:围绕着同一件谋杀,作为画面载体的照片所展现出来的信息是片面的,并在大部分的时间被权贵和媒体所利用;而作为声音载体的录音带,则是主角追寻真相的关键线索。

当电影进行到30分钟处,又出现了「元电影」概念的另一佐证:主角将杂志上的照片以「帧」为单位进行拼贴,最终产生了完整的「胶卷」;第52分钟时,声音与画面最终在「胶卷」上相聚,残缺的信息被拼凑完整,而最终观众所看见的,便是名为「电影」的载体所呈现出来的事实真相。

帕尔玛用两个片段把电影制作工序详细地展现给观众,正如之前所说“一部关于电影幕后制作过程的电影”,除此之外还概括了电影是「声」与「画」共同组成的艺术形式,并将这一母题与影片本身的悬疑类型高度融合,文本与影像在互文中点出这一关系的本质所在:关于「电影」如何以何种形式传递、拆分、整合与隐藏「信息」。

三、重回片头

讲了那么多,现在让我们重新回归到片头,看看帕尔玛是如何通过这样一个片头去展现电影的视觉母题、声音设计母题和故事母题。

一开始便通过指针四次幅度频率不定的摇摆自然带出制片公司、总导演和男女主演员的名字。

注意片头的音效设计:第一次和第二次摆动所配的背景音效都是风声+心跳声,字幕打出制片公司时的音效是较为平缓的,当导演名字出现后,连续出现了三个类似喘息声的音效,正如前面所说,暗示事故/危机的到来。

随后字幕打出的是男主演John Travolta,而这时背景音效取代成车辆失控时的鸣笛声。

随着女主演Nancy Allen的字幕亮相,背景音也转成了影片结尾处那声撕心裂肺的尖叫。

标题大字在银幕上一闪而过,背景音变成枪声和轮胎漏气的声音。

之后便是最妙的设计:片名“BLOW OUT”中的两个单词从屏幕两侧出现,并随着车辆失控打滑的音效不断靠近,就在两个“O”即将重合时,片头结束。

那么这个片头到底秒在哪里?

一、关键视觉元素(表现声音强弱的摇摆指针)、听觉元素(风声、枪声、车辆打滑声和尖叫,而且这些音效是与角色本身挂钩的)和剧情要素(车祸谋杀现场与结尾)的展现:

二、片名中不断靠近两个“O”像是简化后的轮胎,而背景音效也正好对应片中因轮胎漏气的关键情节。

三、考虑到第二点所说的那种「由声入画」的手法,那么两个互相靠近并不断重合的片名也许正是「画面」与「音效」的类比,只有当两者“完全重合”,电影才能将所要表达的信息完全传递给观众。

而上述部分在第一次观影时是很难发觉的,只有重看后才发现片头所潜藏的信息是如此关键,并在形式上与文本内容形成了完美的互文。对于帕尔玛,我只能顶礼膜拜了。

最后聊聊结尾:

很奇怪的是,在之前的帕尔玛电影里,“爱情”这个概念基本都被拿来当作剧情的垫脚石了。《魅影天堂》就是最典型的例子,那部电影里的每一段爱情描写都像是被剧情所裹挟,仓促、机械而套路。尽管我非常中意《魅影天堂》的悲剧结局,但那种震撼跟爱情描写一点关系都没有,不如说爱情戏的粗劣在很大程度上拉低了影片整体的水准。

究其原因,可能是帕尔玛为了不让电影主题偏移而做出的选择,也可能是帕尔玛真心不擅长写爱情戏,亦或是两者皆有。不管怎样,在爱情描写这方面,帕尔玛是真的挺“直男”的(贬义的那种)。

所以在《凶线》里,尽管漫天烟火与背景音乐所营造的氛围是那么忧伤,我仍然把这种桥段的存在看作是帕尔玛为了“煽情”而刻意为之。除了惊叹于视觉效果外,其他的部分(尤其是情感)我还真没什么感受。

直到“尖叫声”的再度亮相:在最后的最后,男主反复听着那段让人痛心不已的录音,并用女主被杀前最后一声刻骨铭心的尖叫替换了之前那个蹩脚的音效,于是《凶线》的剧情在谋杀与爱情上绕了那么一大圈,最后又回到这部“粗制滥造”的B级片上。

正如前文所言,「画面」与「音效」融合后所传递的信息是一致的,但最后的这个情节设计又把这一理论给无情粉碎。当观众经历了全部剧情后,在情感上就形成了一种难以言喻的「声画对立」。承载着爱情记忆的尖叫,在B级电影里被画面扭曲成廉价的感官刺激符号,对于男主的想法,我们永远无从得知;他把这段记忆铭刻在一部B级恐怖片上,电影会承载这段记忆吗?亦或是通过影像的扭曲来遗忘痛苦,我们也只能猜测。于是,此前一直脱节的情绪在这一瞬间终于升华,压抑的情感始终无法宣泄,骨鲠在喉,难以释怀。爱情被赋予了实体,完成了属于「元电影」的叙事回环。

再联想到之前关于“声画分离导致真相被掩盖”的言论,这一次,声画重组所带来的是更深层次的紊乱,不禁让人思考:声与画,到底是谁才能引导并决定我们所感知的真相?

也许是娱乐。

一切只为娱乐,声与画都是被娱乐所裹挟的傀儡,在狂欢的浪潮之下,一切情感反馈都是被提前设置好的,于是那声尖叫最后所承载的悲情也变得毫无意义,意义被观众赋予,被观众所决定,最后又反馈给观众本身。

一切皆是娱乐。

这是我第一次在帕尔玛的电影里看见“真情”。

被「电影」所围绕的真情。

3 ) 完美尖叫

政治惊悚片。帕尔马总有富有创造力的镜头,这部片子中的裂焦镜头多而精妙,Jake和猫头鹰、Jake听到警察和官员谈话、死鱼和女性受害者,都是非常精湛的构图。Jake在工作室里找录音带那一段9*360°的旋转镜头令人印象深刻。Jake在烟花下抱住妓女尸体的镜头明明很俗套,却拍出了超乎常人的美感。 剧作的开端很抓人,一名电影音效师,在桥上采集素材时偶然捕捉到州长开车落水前的枪响,又下水救了车里的妓女。政治迫害和州长召妓的秘密就这样偶然被Jake发觉,而召妓其实也是对手雇佣摄影师曼尼·卡普和妓女设下的圈套。Jake剪下杂志刊登的卡普拍摄的车祸照片,与录音拼凑成了完整证据,且发觉了照片中微微一抹疑似枪械的银光。而敌对势力则抹除了Jake的原录音,并时刻准备除掉三个知情人,销毁全部证据。 竞选对手其实内部不合,原方案是制造召妓丑闻取回照片,但组织中的杀手却擅自行事,直接了解了州长的姓名。杀手善后的手段很老道,偷换了事故车辆上中弹的轮胎,用爆胎混淆视听。为了做掉妓女并掩盖其真实死因,提前连杀两名具有相似体貌特征的女性,再用公用电话报警“自白”,伪造成连环杀手。最后冒充电视主持人,以协助公开真相为由约出妓女,把证据扔进湖里销毁后,在独立日游行的国旗下行凶。虽被及时赶到的Jake反杀,但Jake也永远失去了公开真相的机会。 妓女临死前的真实尖叫成为了新片中正需要的声音素材,而Jake也只能听着妓女临死前的录音怀念亡者,在剪辑室里抽着烟自嘲:真是完美的尖叫啊。

4 ) Blow Out

5 ) pauline-kael的评论

转载于://scrapsfromtheloft.com/2018/07/17/blow-out-pauline-kael/

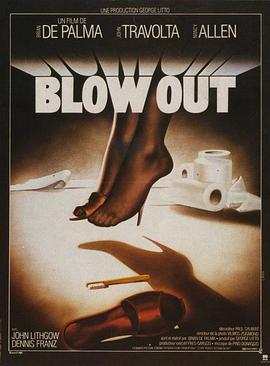

At forty, Brian De Palma has more than twenty years of moviemaking behind him, and he has been growing better and better. Each time a new film of his opens, everything he has done before seems to have been preparation for it. With Blow Out, starring John Travolta and Nancy Allen, which he wrote and directed, he has made his biggest leap yet. If you know De Palma’s movies, you have seen earlier sketches of many of the characters and scenes here, but they served more limited—often satirical—purposes. Blow Out isn’t a comedy or a film of the macabre; it involves the assassination of the most popular candidate for the presidency, so it might be called a political thriller, but it isn’t really a genre film. For the first time, De Palma goes inside his central character—Travolta as Jack, a sound effects specialist. And he stays inside. He has become so proficient in the techniques of suspense that he can use what he knows more expressively. You don’t see set pieces in Blow Out—it flows, and everything that happens seems to go right to your head. It’s hallucinatory, and it has a dreamlike clarity and inevitability, but you’ll never make the mistake of thinking that it’s only a dream. Compared with Blow Out, even the good pictures that have opened this year look dowdy. I think De Palma has sprung to the place that Altman achieved with films such as McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Nashville and that Coppola reached with the two Godfather movies—that is, to the place where genre is transcended and what we’re moved by is an artist’s vision. And Travolta, who appeared to have lost his way after Saturday Night Fever,makes his own leap—right back to the top, where he belongs. Playing an adult (his first), and an intelligent one, he has a vibrating physical sensitivity like that of the very young Brando.

Jack, the sound effects man, who works for an exploitation moviemaker in Philadelphia, is outside the city one night recording the natural rustling sounds. He picks up the talk of a pair of lovers and the hooting of an owl, and then the quiet is broken by the noise of a car speeding across a bridge, a shot, a blowout, and the crash of the car to the water below. He jumps into the river and swims to the car; the driver—a man—is clearly dead, but a girl (Nancy Allen) trapped inside is crying for help. Jack dives down for a rock, smashes a window, pulls her out, and takes her to a hospital. By the time she has been treated and the body of the driver—the governor, who was planning to run for president—has been brought in, the hospital has filled with police and government officials. Jack’s account of the shot before the blowout is brushed aside, and he is given a high-pressure lecture by the dead man’s aide (John McMartin). He’s told to forget that the girl was in the car; it’s better to have the governor die alone—it protects the family from embarrassment. Jack instinctively objects to this cover-up but goes along with it. The girl, Sally, who is sedated and can barely stand, is determined to get away from the hospital; the aide smuggles both her and Jack out, and Jack takes her to a motel. Later, when he matches his tape to the pictures taken by Manny Karp (Dennis Franz), a photographer who also witnessed the crash, he has strong evidence that the governor’s death wasn’t an accident. The pictures, though, make it appear that the governor was alone in the car; there’s no trace of Sally.

Blow Out is a variation on Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966), and the core idea probably comes from the compound joke in De Palma’s 1968 film Greetings: A young man tries to show his girlfriend enlarged photographs that he claims reveal figures on the “grassy knoll,” and he announces, “This will break the Kennedy case wide open.” Bored, she says, “I saw Blow-Up—I know how this comes out. It’s all blurry—you can’t tell a thing.” But there’s nothing blurry in this new film. It’s also a variation on Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), and it connects almost subliminally with recent political events—with Chappaquiddick and with Nelson Rockefeller’s death. And as the film proceeds, and the murderous zealot Burke (John Lithgow) appears, it also ties in with the “clandestine operations” and “dirty tricks” of the Nixon years. It’s a Watergate movie, and on paper it might seem to be just a political melodrama, but it has an intensity that makes it unlike any other political film. If you’re in a vehicle that’s skidding into a snowbank or a guardrail, your senses are awakened, and in the second before you hit, you’re acutely, almost languorously aware of everything going on around you—it’s the trancelike effect sometimes achieved on the screen by slow motion. De Palma keeps our senses heightened that way all through Blow Out; the entire movie has the rapt intensity that he got in the slow-motion sequences in The Fury (1978). Only now, De Palma can do it at normal speed.

This is where all that preparation comes in. There are rooms seen from above—an overhead shot of Jack surrounded by equipment, another of Manny Karp sprawled on his bed—that recall De Palma’s use of overhead shots in Get to Know Your Rabbit (1972). He goes even further with the split-screen techniques he used in Dressed to Kill (1980); now he even uses dissolves into the split screen—it’s like a twinkle in your thought processes. And the circling camera that he practiced with in Obsession (1976) is joined by circling sound, and Jack—who takes refuge in circuitry—is in the middle. De Palma has been learning how to make every move of the camera signify just what he wants it to, and now he has that knowledge at his fingertips. The pyrotechnics and the whirlybird camera are no longer saying “Look at me”; they give the film authority. When that hooting owl fills the side of the screen and his head spins around, you’re already in such a keyed-up, exalted state that he might be in the seat next to you. The cinematographer, Vilmos Zsigmond, working with his own team of assistants, does night scenes that look like paintings on black velvet so lush you could walk into them, and surreally clear daylight vistas of the city—you see buildings a mile away as if they were in a crystal ball in your hand. The colors are deep, and not tropical, exactly, but fired up, torrid. Blow Out looks a lot like The Fury; it has that heat, but with greater depth and definition. It’s sleek and it glows orange, like the coils of a heater or molten glass—as if the light were coming from behind the screen or as if the screen itself were plugged in. And because the story centers on sounds, there is a great care for silence. It’s a movie made by perfectionists (the editor is De Palma’s longtime associate Paul Hirsch, and the production design is by Paul Sylbert), yet it isn’t at all fussy. De Palma’s good, loose writing gives him just what he needs (it doesn’t hobble him, like some of the writing in The Fury), and having Zsigmond at his side must have helped free him to get right in there with the characters.

De Palma has been accused of being a puppeteer and doing the actors’ work for them. (Sometimes he may have had to.) But that certainly isn’t the case here. Travolta and Nancy Allen are radiant performers, and he lets their radiance have its full effect; he lets them do the work of acting too. Travolta played opposite Nancy Allen in De Palma’s Carrie (1976), and they seemed right as a team; when they act together, they give out the same amount of energy—they’re equally vivid. In Blow Out, as soon as Jack and Sally speak to each other, you feel a bond between them, even though he’s bright and soft-spoken and she looks like a dumb-bunny piece of fluff. In the early scenes, in the hospital and the motel, when the blonde, curly-headed Sally entreats Jack to help her, she’s a stoned doll with a hoarse, sleepy-little-girl voice, like Bette Midler in The Rose—part helpless, part enjoying playing helpless. When Sally is fully conscious, we can see that she uses the cuddly-blonde act for the people she deals with, and we can sense the thinking behind it. But then her eyes cloud over with misery when she knows she has done wrong. Nancy Allen takes what used to be a good-bad-girl stereotype and gives it a flirty iridescence that makes Jack smile the same way we in the audience are smiling. She balances depth and shallowness, caution and heedlessness, so that Sally is always teetering—conning or being conned, and sometimes both. Nancy Allen gives the film its soul; Travolta gives it gravity and weight and passion.

Jack is a man whose talents backfire. He thinks he can do more with technology than he can; he doesn’t allow for the human weirdnesses that snarl things up. A few years earlier, he worked for the police department, but that ended after a horrible accident. He had wired an undercover police officer who was trying to break a crime ring, but the officer sweated, the battery burned him, and, when he tried to rip it off, the gangster he hoped to trap hanged him by the wire. Yet the only way Jack thinks that he can get the information about the governor’s death to the public involves wiring Sally. (You can almost hear him saying “Please, God, let it work this time.”) Sally, who accepts corruption without a second thought, is charmed by Jack because he gives it a second thought. (She probably doesn’t guess how much thought he does give it.) And he’s drawn to Sally because she lives so easily in the corrupt world. He’s encased in technology, and he thinks his machines can expose a murder. He thinks he can use them to get to the heart of the matter, but he uses them as a shield. And not only is his paranoia justified but things are much worse than he imagines—his paranoia is inadequate.

Travolta—twenty-seven now—finally has a role that allows him to discard his teenage strutting and his slobby accents. Now it seems clear that he was so slack-jawed and weak in last year’s Urban Cowboy because he couldn’t draw upon his own emotional experience—the ignorant-kid role was conceived so callowly that it emasculated him as an actor. As Jack, he seems taller and lankier. He has a moment in the flashback about his police work when he sees the officer hanging by the wire. He cries out, takes a few steps away, and then turns and looks again. He barely does anything—yet it’s the kind of screen acting that made generations of filmgoers revere Brando in On the Waterfront: it’s the willingness to go emotionally naked and the control to do it in character. (And, along with that, the understanding of desolation.) Travolta’s body is always in character in this movie; when Jack is alone and intent on what he’s doing, we feel his commitment to the orderly world of neatly labeled tapes—his hands are precise and graceful. Recording the wind in the trees just before the crash of the governor’s car, Jack points his long, thin mike as if he were a conductor with a baton calling forth the sounds of the night; when he first listens to the tape, he waves a pencil in the direction from which each sound came. You can believe that Jack is dedicated to his craft because Travolta is a listener. His face lights up when he hears Sally’s little-girl cooing; his face closes when he hears the complaints of his boss, Sam (Peter Boyden), who makes sleazo “blood” films—he rejects the sound.

At the end, Jack’s feelings of grief and loss suggest that he has learned the limits of technology; it’s like coming out of the cocoon of adolescence. Blow Out is the first movie in which De Palma has stripped away the cackle and the glee; this time he’s not inviting you to laugh along with him. He’s playing it straight and asking you—trusting you—to respond. In The Fury, he tried to draw you into the characters’ emotions by a fantasy framework; in Blow Out, he locates the fantasy material inside the characters’ heads. There was true vitality in the hyperbolic, teasing perversity of his previous movies, but this one is emotionally richer and more rounded. And his rhythms are more hypnotic than ever. It’s easy to imagine De Palma standing very still and wielding a baton, because the images and sounds are orchestrated.

Seeing this film is like experiencing the body of De Palma’s work and seeing it in a new way. Genre techniques are circuitry; in going beyond genre, De Palma is taking some terrifying first steps. He is investing his work with a different kind of meaning. His relation to the terror in Carrie or Dressed to Kill could be gleeful because it was pop and he could ride it out; now he’s in it. When we see Jack surrounded by all the machinery that he tries to control things with, De Palma seems to be giving it a last, long, wistful look. It’s as if he finally understood what technique is for. This is the first film he has made about the things that really matter to him. Blow Out begins with a joke; by the end, the joke has been turned inside out. In a way, the movie is about accomplishing the one task set for the sound effects man at the start: he has found a better scream. It’s a great movie.

The New Yorker, July 27, 1981

6 ) 重解《凶线》:是“政治阴谋”还是帕尔玛的叙述性诡计?

但是,由于我个人觉得在帕尔玛70年代末到80年代初的以悬疑惊悚恐怖元素为卖点的三部影片中,本片的剧情是最强的,其次是《The Fury》,最后才是《Dressed to Kill》。所以这篇影评我将抛开一切技术环节,关于本片各种镜头技巧的华丽运用,我想大家的溢美之词已经够多了,不需要我再来添上一笔。就单纯的谈谈我对本片剧情的理解和看法好了。当然,这一切都纯属个人见解。

首先是本片的剧情,我就不再做详细赘述了。我们都知道,男主角杰克在郊外采集风声样本时,无意中目睹并录下了总统候选人,现任州长乔治麦莱恩车祸死亡的全过程,并救下了和他共乘一辆车的萨丽.....再后来,当杰克重新回放事发现场的录音样本时,才发现原来在车子撞毁之前曾有一声枪响,随着事件的逐步调查,我们才发现,原来是有人用枪射穿了麦莱恩的车胎,才致使车子撞翻到河里的,这一切的事件都表明麦莱恩的死其实一场早有预谋的政治迫害.......

其实对于早已看惯好莱坞商业片的观众而言,这样的故事早已不是什么新鲜事了,反映政治谋杀的,比《凶线》刺激火爆的电影比比皆是,在观看影片的过程中,我甚至觉得悬念的铺陈和剧情的推进实在是太顺汤顺水了,男主角和女主角勾搭上,凶手的暗中破坏,随即男主角又发现女主角其实也参与了事件其中,但随即又告诉我们女主角对事件真相又毫不知情,这一类的梗其实是这类影片中早已玩腻的一套。

但是,令我彻底对本片改观的是,帕尔玛终于在影片快要结束的最后20几分钟里来了一个彻底的大逆转和大颠覆。而这个逆转,正是凶手在火车站谋杀妓女的那一场戏里让我对该片的剧情有了恍然大悟般的体会。

随着影片的进行,我们后来都了解到,麦莱恩的死其实是一场意外。他的政治对手本来想制造一场“性丑闻”事件,也就是后来把事发现场的影片组图高价卖给杂志社的摄影师卡普尔,是他同萨丽合作,让她接近这位高官。再由本片幕后的那位凶手伺机给车做些手脚,让车出点小事故,到时候警察一赶到,照片一拍到,给他冠上个“候选人公然招妓”的丑闻,以起到打压对手的目的。但是由于那名幕后凶手的失误,却导致了麦莱恩的死亡,于是整部影片仿佛成了男主角调查真相,以及那名幕后凶手不断制造麻烦去掩盖真相的过程中产生的一种“角逐”的感觉。

但是,事情真的如此简单吗?那名幕后凶手真的是因为一时的失误而使得麦莱恩死亡,并最后残忍的杀害了女主角萨丽的吗?

我个人并不这么认为。

而剧情的古怪和精妙也正是在此,那名幕后凶手,径直朝车胎开了一枪,而地点偏偏不选在别处,而是车子快要过河的时候。而在影片开头,男主角在桥上采集声音样本时,河边有对男女正在对话,此时的镜头中我们很明显就能发现,护河的栅栏是木制的。在这里实行计划,很明显是叫麦莱恩送死啊,可是,我们在影片的中间部分发现那位幕后主使在给那名幕后凶手打电话的过程中语气不是一般的恼火,很显然他并不想节外生枝,而那名幕后凶手,我们发现他也是一个非常冷静和聪明的人,他知道去把事发车辆的轮胎换掉,也知道把男主角的录音带给洗掉。可是就是这样一个聪明的凶手,这样一场精心策划的政治阴谋,竟然会选择这样一个错误的地点进行?

而奇怪的还不仅仅如此,在影片的后半段过程中,表面上凶手一直在阻挠着男主角进行调查,洗掉他的录音带等等,但是对于本片中最单纯最一无所知的女主角,他却总是大开杀戒。影片中知道真相的三个人中,男主角杰克,摄影师卡普尔和妓女萨丽,作为观众,您认为这三个人中谁最危险呢?明眼人都知道1是男主角杰克,因为他手上不仅有录音证据,还不依不挠的调查真相,2则是摄影师卡普尔,这家伙认钱不认人,手头有了钱他也不会把事件真相公之于众,而排在第三的才是萨丽,表面上萨丽是当时和麦莱恩最接近的人,但事实上她根本一无所知,她最后知道的真相也是男主角杰克不依不挠的告诉她的。而观看影片的过程中,你同样可以发现,萨丽简直就是一个非常天真无脑的女孩儿。

可就是这样一个女孩,为何却首先被那位幕后凶手相中,一直展开追杀呢。我想明眼人都知道第一是该杀了杰克,毁掉一切录音证据,再来干掉摄影师以防节外生枝,最后才解决掉这个傻兮兮的妓女吧。

但是,不管是何种原因,这名幕后凶手不仅第一个就“看中”了萨丽,而且还上演了本片中最为重要的一个环节—“误杀”

当凶手追踪一个外表和服饰酷似萨丽的女子穿过市场,来到车站的时候,伺机下手,但是随后就发现这名女子并不是萨丽,但是事已至此,只能将错就错,把其杀害了。

这个情节看上去很简单,但实则不然。在我刚才提到的也就是影片最后20来分钟里,一场惊人的反转把看上去十分线性和合理性的剧情给彻底搅乱了。也就是这名凶手假扮记者,在车站等待萨丽的过程里,他再一次行凶杀死了一名妓女,而且同样留着卷发,长相也酷似萨丽。 这个情节的安排的巧妙之处在于,这名幕后凶手在事前自己已经给警方拨打了一个电话,装作一名“Psycho killer”说自己杀死了一名女子。很显然,他是想在杀死萨丽以后,让警方把一切线索都归结到一个有着特殊性喜好的变态杀人狂身上。但是这样做的奇怪之处在于,这样的“变态杀人狂”岂不是要闹的更加不可开交,也更加节外生枝吗?而另一个奇怪的点是,这名幕后凶手,在等萨丽的过程中顺手又解决掉一个,到底是再让这个“Psycho killer”的游戏显得更加真实,还是有些多余呢?我是说在一个误杀之后顺手想出来的主意,需要再主动去再谋杀一个局外人,来添加真实性吗?

让我们再来看看这名幕后凶手是怎样杀人的吧,他总是用手表中隐藏的钢丝去勒死受害者。首先这种“武器”的选择就很有问题,而最最令人震撼的是第一场谋杀中,这名凶手在已经勒死受害者后,他又干了些什么呢?他当时在市场顺手拿走了一个冰锥,当他发现自己其实是杀错了人的时候,他还是又继续用冰锥接连刺了受害者数刀。请问这样的杀人方式究竟是政治阴谋中解决掉牺牲品的方式还是享受杀害女性受害者以达到快感的刺激方式呢?

联系一下,影片开头中麦莱恩的死。表面上是这名幕后凶手的一个失误,还是其实他的真正目的并不是针对麦莱恩而是“萨丽”?亦或是“萨丽”这种类型的女性受害人呢?

终上所述,影片中的种种疑点,无不指向这名幕后凶手,表面上作为一名政治家的“幕后黑手”为自己的本职工作,可是,在一次执行任务的过程里,本来只是想单纯的制造一场“性丑闻”事件,谁想到摄影师卡普尔手下的那名“妓女”正是自己偏爱的“受害者类型”。于是,在计划的进行中,本来只想制造一场小小计划的他,还是忍不住把事情弄“大条”了,让车子翻入水中,使麦莱恩和这名妓女都统统死在水中不正好是一箭双雕的好办法吗?

还记得卡普尔的那句话吗?他说自己不懂水性。可是计划的唯一不完美之处就在于男主角杰克的出现。

但是,布莱恩德帕尔玛始终没能告诉我们真正的答案。一切的情节设置都可以看作是一场出了“乱子”的政治谋害事件背后引发的一连串效应。

但是,影片的开头大家还记得吗,是一场紧张的B级恐怖片里女子被变态杀手所杀的情景,但是直到业余的演员发出的不专业的尖叫声时才破了梗。而杰克正是B级恐怖片的录音师,当他遇到了麦莱恩的死之后,所有人都说这只是一个意外,而他却偏偏要调查事情的真相,曾经做过警察的他对这种政治阴谋事件欲罢不能。以至于,他忽略了电视上正在播出的第一名死者的新闻报道。

可是,当影片的结尾,萨丽的尖叫声恰好配合在这样一部B级恐怖片里作为配音的时候,这尖叫声是如此完美,这就是被无情杀手所谋害的单纯女性临死前最刻骨铭心的最后一声尖叫。请问,她的死究竟是因为“政治”还是一场最单纯的“变态杀人”游戏呢?

35mm Im crying... absolutely amazing QAQ (每次进入没有办法100%认真看片 焦虑/轻度抑郁 学术没有心思的时候就把高潮戏翻出来看一遍 每次都会有想大哭一场的程度 以后再被问到最喜欢的电影是什么 就是这部了 无法取代了暂时)

simplistic hollywood remake of Antonioni's Blow up. It does has it's moments though.

惊魂记浴室尖叫,西北偏北俯拍,夺魂索布假景,窃听大阴谋窃听,“放大”声音。这些他者印记加上开头戏中戏长镜和九圈360度长镜,以及野外录音剪辑处理,技巧让人跪服。故事依旧是由技术复制时代对人的异化起,但没有达到期待高度。从寻找尖叫到想摆脱尖叫,楼顶烟火忆起新桥恋人。

本片可谓迷影堆彻类作品中成就最高的一部。河边录音和简报成影等几段专业操作实在太酷了!虽然观者已知创意源头来自安东的放大和科波拉的大窃听但丝毫不影响我们对它的欣赏和喜爱。另个重要迷影源头当然是希区柯克。投河救人的第一次与拯救失败的第二次显然照搬迷魂记。但个人对于用高调悬念手法(观众全知而角色不知)去处理最后一幕持保留看法。希区曾解释自己的悬念错用:过于残酷让小男孩被炸死,并非错误症结的所在。真正败笔在于观众的紧张情绪没有得到有效释放。在他们已知炸弹被带上了车,也知炸弹可能在几点爆炸的情况下,唯一合理的悬疑终结手段就是让炸弹被发现并被转移到安全处引爆。换句话说,此处情节设计虽然很写实,但却破坏了悬念的结构,没有满足和调动观众正常的心理需求……男孩之于炸弹如此,莎莉之于拯救也应是如此!三星半。

拼接希区柯克,奥菲尔斯,科波拉,安东尼奥尼各个的一部分,放置到自我感动的故事里,真是帕尔马的平实优点和缺点,那个旋转的长镜头确实很炫......

拍摄手法传承希区柯克,情节及节奏则有Blow-up的影子。剪辑、配乐和镜头设计都极有看头。缺点在于影片的形式远大于内容,人物二维化,表演脸谱化,以致结尾失连,前后情绪脱节。

华丽的技巧,十足的紧张感,开场戏中戏两个帕尔玛最拿手的长镜拼贴,结局烟花灿烂与斯人已逝的对比,一个原本普通的故事被打造得足够精彩。

3+...考虑到出产年份,这片还是很高质量大制作的...大家都推崇烟火场景,我倒觉得上帝视角拍屈伏塔开车穿过一片古建筑更有感...

感觉那个时期的布莱恩·德·帕尔玛电影都是剧本和故事很普通,但是技术很牛逼。

技法依旧神乎其神,印象最深的是听录音时通过主观视角拼贴还原案发事件,以及那个N圈的旋转镜头。音乐是败笔,无处不在的配乐塞得太满了,既然有那么牛逼的镜头语言实在没必要再靠这一招渲染气氛和情绪,少而精才是王道,成功之例可见于《惊魂记》。高潮部分慢镜+去掉背景音也有些肉麻了。

太厉害!虽然剧情和立意有点弱,但瑕不掩瑜,从技术层面来看简直棒呆,太开眼,调度、运镜、构图…快要玩出花来了,不拘一格,各种炫目和惊叹,特拉沃尔塔口音太重了,一听便知,论声效的重要性,最真实的反应源于惨烈可怖的现实体验,绝妙的呼应和衔接,又一个神结尾,为帕尔玛的硬实力献上膝盖。

从《放大》到希区柯克,精彩的环节还是在的,甚至前--六分之五都很好啊,但是最后部分突然搂不住了是怎么回事,拍high了吗?满溢的配乐,汹涌的情感,都让我招架不住啊。。。(另外豆瓣这个又名: 爆裂剪辑 是怎么回事。。。

整体看来,味道很怪,有希区柯克的味道,但有不仅限于希区柯克,凶杀氛围营造的很赞,很有味道,故事层层递进,但是有点闷,最后来个前后呼应,也算文章平淡做法。看到最后,在那漫天烟花下,男主角抱着死去的女主角失声痛哭时,让我给这部电影加上了爱情的标签

#蓝光重刷计划# 布莱恩·德·帕尔玛接过希区柯克的衣钵,看到不少致敬大师的影子,同时也把自己的风格发挥到的淋漓尽致,我倒是很爱这种留白式做减法的叙事,比如最后那个“最棒的尖叫”,更让人觉得意味深长。

De Palma对剪辑、摄影、配乐、音响等技法的运用出色至极,开场的段落给人一种惊艳之感!而结尾与开头的呼应也使影片更令人回味。

德·帕尔玛媒介自反最好的一部。此前Blow-up讲过了画面,Conversation又讲了声音,本片的巧思之处在于,从声音切入来讲声画的同步。从而将一个后肯尼迪之死时代的政治阴谋故事,嫁接到电影的后期制作过程上,继而达成一个漂亮的元电影回环。

四星半,偷师希区柯克和安东尼奥尼,德帕尔马是新好莱坞中最娴熟的改装主义者、技术控达人。強烈且可感知的摄影机存在,凶杀场面是典型的希区柯克在场,双屏、剪辑、音效、长摇镜头等等,不遗余力的改造强化电影的表现力,把旧有的类型和题材重新包装改造,加入更加现代的视角和技法融入到整个叙事当中。他从过去抵达现代。

1.录音师的真相求索之路,悬疑惊悚版[放大]。2.帕尔玛的镜头调度令人着迷,如片首戏中戏的杀手主观长镜、剪辑室9圈旋转长镜及大量大俯角镜。3.浴室尖叫致敬[精神病患者],高潮以脸上映照的烟花五彩闪光彰显惶惑凄楚心境,同质于[夺魂索]。4.地铁追逐戏如[情枭的黎明]预演。5.大桥收音分镜。(8.5/10)

和所有的“迪庞马”片的毛病一样:虎头蛇尾。开篇slasher/giallo的致敬惊艳,“谜题”的铺陈设置貌似妙笔连连,到现象的重构时有趣的细节已被抛弃,最终的解决只能用“导演在找借口结束本片"来解释。和模仿对象Blow Up比较两片的结构完全一样,只不过一个是上坡一个是下坡

他妈的,居然是转圈长镜头