详细剧情

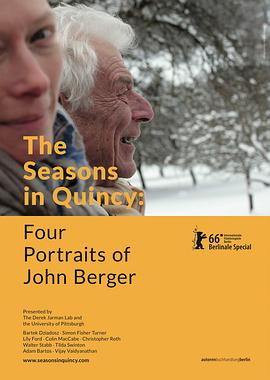

梁文道称:“约翰•伯格是西方左翼浪漫精神的真正传人,一手是投入公共领域的锋锐评论,另一手则是深沉内向的虚构创作。”约翰•伯格于今年1月离世,使得这部纪录片成为他晚年生活弥足珍贵的记录影像。

影片由四部风格迥异的短片构成,串联起一年四季。以约翰·伯格生前所居住过的小镇昆西为背景,用平实的故事以及诗一般的画面,为约翰·伯格褪去艺术家和名人的光环,还原成一位普通的老人,真诚质朴。小村庄中的居民也各有故事。导演也用更多历史影像穿插融合在老人的生活中,给人以诗的穿越感和遐想的空间,是一部非常优美的纪录片。

长篇影评

1 ) 住在阿尔卑斯山的John Berger

这部纪录片分四个部分,有两个主角。处在全片核心的这一位是作家、画家、有时还会出现在很多纪录片里当解说员的John Berger,另一位是近些年经常出现在国际电影节上的女演员Tilda Swinton,也是本片的四位导演之一。两人都来自于伦敦,生日在同一天,父亲都曾参军,却是年龄相差34岁的忘年好友。这部纪录片的标题,也就是两人对话的起点,就在阿尔卑斯山脚下的Quincy,John Berger大部分的时间都住在这里。Swinton从削苹果的方式共情到两人对父亲的回忆,然后在不同的素描画像中感受对方的心境,再到生活中的趣事。展现了一个脱离了艺术家身份的John Berger。跟如今的很多纪录片相比,这部纪录片的规模算是比较简陋,除了两位大名鼎鼎的当事人。但是里面的情感共振还是挺强的,他会说出一些看似平淡随意却让人感受到大量信息的话,例如:“劳动才能让你更好的融入土地。”Swinton读的那首诗很打动我,叫《第七个》,也是John Berger的著作:“如果你要来到这世界上,最好出生七次,……你自己必须是那第七个。也许意识到一切皆是轮回,这位老人才显得如此睿智,有力量。可惜的是,本片上映的第二年,他就去世了,也是在一个冬天,白雪覆盖了阿尔卑斯山。

2 ) 记录

●所有照片都是造访的一种方式,或是缺席的一种表达。

●我觉得我们好像前世就认识或共事过,约好在此世相遇,在同一车站下车,但没有商量好时间。

●每头狮子既属于狮群又独立存在,每头牛归于牛类又个性分明。动物被支配同时也被崇拜,这可能是首个存在主义二元论。

●不确定感和希望有关联。

●纵向的连续性:我们生活在一个可以无限延展的时代,但在昆西小镇,这种延展是纵向的,尽头是死亡。

●只要你懂得倾听,故事会不断向你涌来。

● 很简单地,当你踩下油门,你的机车飞驰出去。顺着你的视线望去,每当遇到障碍物,找到这根线,你会知道你要去向哪里。

3 ) Quote

If you set out in this world, better be born seven times. Once in the house on fire, once in a freezing flood, once in a wild madhouse, once in a field of ripe wheat, once in an empty cloister, and once among pigs in sty. Six babes crying, not enough. You yourself must be the seventh. When you must fight to survive, let your enemies see seven. One, away from work on Sunday. One starting his work on Monday, one who teaches without payment, one who learned to swim by drowning, one who is the seed of a forest, and one whom wild forefathers protect. But all their tricks are not enough, you yourself must be the seventh.

两个年代的出生者——敏感出于:生于战争,反抗战争。

红白格子法兰绒衬衣,红色裤子红色窄皮带,金色短直发。

storyteller rather than a writer。

动物无声有灵,和人类不同,它们是更接近生命本身的。存在于动物中的自然哲学,存在主义,动物对于死亡有理解或感受吗?甚至是人类也不见得明白死亡意味着什么。

影片如何将政治贯穿其中?

the alienation effect——一份utopian假报纸却驱使人们读完,把这种不可能变成可能的假象是一种希望,fake but positive。

在地狱里,团结才重要,而不是在天堂,是不是这样——继而前后播放了毛主席是太阳及对布尔什维克的颂歌,众认同。

左翼,右翼,及茶党。John—political artist:承认围绕在我们身边的地狱以及我们对团结的需要,但人们仍然存在着对感官世界的开放和关注的态度,从未消失,它不只是有受难及绝望;缅怀或记住过去的经历及生活方式,but there is no nostalgia,它不只限于左翼党派叙述事情发展的可能性,也不限于茶党不明确其历史中的偏向,它教我们用一种感官的 情感的 性欲的 神经质的方式来理解,因为政治家们必须掌控这些力量。

John是共产主义者,for marxist and artist, nothing is trivial,it embraces all life. 他认为自己最有价值的一本书,the seventh man,指向migrant workers外国来的务工者,发现了这些劳动者很社会化的生活,其实不是pessimism的。

丰收,harvest。

Beverly 种了一院子的树莓—— 去摘一大碗树莓,送给喜欢的人;或者若自己喜欢,就去摘一碗,加一些糖和奶油,或者什么都不要加,找一张beverly的照片放在旁边——because your pleasure would give her pleasure。

冬天牛羊群会被赶到更高海拔的牧地吃草1300-1400 Alpagle. 山谷里的花在那里bloom brighter,the blues are bluer and the yellow are yellower 放牧的人shepherd可以通过牛的铃铛响声判断是哪头牛。

Village,Vally——农民看到的美不一样。the beauty would come from the value of the work which has been put into that landscape and shaped that landscape——detail reviews something of the work done of it细节能够体现对事物的劳作。

John认为,乡间,这个视野会特别开阔的地方,有某种地平线一直存在,永远不会被封闭。因为这种开放——每个季节的特别之处,它不是强加于你的,而是你主动适应栖居。

肖像画,木楼,堆满杂物的画室,金属材料,木料,没有粉刷的屋子。小姑娘陪爸爸印好肖像画,和姐姐唱杯子歌,背景音转为水滴。静止又流动的只是时间。

她们再制作祈福材料,再练杯子歌的技巧,再摘树莓,光线明亮,房屋粗陋。这一大碗红色树莓,她们围在一起,带着母亲的照片和肖像画,坐在草地上吃了起来。

“homeland connects with mother tongue.”

4 ) 速记

第一段是Tilda和伯格的老友记,说到了同天生日和同为军人子女,借由自己家庭经历讲人类经验传递“历史从不自断舌根”。致敬Ways of Seeing

第二段讲人类与动物的观照(恰遇伯格妻子逝世),其中有名与实、语言与存在的问题,一头狮子曾是狮子,引德里达说“我所是的动物”,对它者的探讨,语言(不通)是人与动物之间的一道深渊,海德格尔说语言是存在之屋人通过语言预知死亡然后向死而生,伯格说别闹啦我们作为会死的动物去说动物不理解死亡不是很可笑么。

第三段讲政治与叙事,自由主义经济失败但是意识形态输出成功,以至于毫无alternative,左翼要集合力量,资深老左伯格发问:well在地狱里我们才需要团结,天堂里,不存在的,不是吗?大家尬笑。红色歌曲蒙太奇。

第四段回归昆西乡野,用镜头语言讲人如何生活在自然中,伯格说在乡野你总是有一个horizon,四季不是降临在你身上,而是与你共生inhabit。钢琴配乐new age风。

总结:相约昆西,伯格的哲学课。

5 ) 小记:一些台词

再看《昆西四季》,被片中更多的片段打动。对最近一段时间的自己启发很大,记录于此。

·战争的沉默

I mean, there’s one specific kind of silence which I personally struggled with, which is the idea of not talking to one’s children about such... possibly the inability to hand this on. You know, we talk a lot about handing experience on, “standing on each other’s shoulders”, and so the idea of your experience kind of being cauterized, and not handing it on to your children, such as my father’s generation. That silence is what I’m talking about.… And I suppose that they would say, “well, we fought so that we wouldn’t have to talk to our children about it, we fought so that our children wouldn’t know. But, “history cannot have its tongue cut out.”It doesn’t really work, that silence, because the curiosity and the need to know is still there. And they need to learn. It is not the going into battle that I find most difficult to imagine, it is coming back from battle.

The resistance of the word “inconsequential”. “To protest is to refuse being reduced to a zero and to an enforced silence. Our protests by building a barricade, taking up arms, going on a hunger strike, linking arms, shouting ,and writing, in order to save the present moment, whatever the future holds.”

·叙事,信息,与现代性

And each lion was lion, each ox was ox.

For me, a storyteller is like a passer. I mean that’s very like somebody gets contraband across the frontier. I mean, stories come to you all the time, if you listen if you listen, if you listen.

One of the features of our time is that people worship ideas. And objects, but ideas particularly. Quite arbitrary, without really understanding their meaning. I mean, take modern art. The idea of modernity, this is the criteria by which people judge things without really enquiring what makes things modern, if the thing is really modern.

I think the idea of information is power, that just more information informs a public has been disproved, right? I mean that is to say that the war crimes of the Bush administration or whatever, are just there in plain sight. But it was kind of like when you have such of this excess of information that isn’t organized, it just all becomes a kind of noise... And people are bored like there is too much of it.

In the monopolistic religions, there is this notion of Heaven and Hell. Different interpretations but these two categories. And it’s worth asking the question are the following: It’s in Hell where solidarity is important, not in Heaven, isn’t it?

The two things about John’s work that will always make me think of him as a political artist that really matters now, is that While there is a commitment-an unwavering commitment to a recognition of the hell that surrounds us and the need for solidarity, there is also an openness and attention to the sensual world that never goes away. It isn’t just baleful, it isn’t just suffering or despairing that even though it can lead to more suffering in a certain way, there is a commitment, a total commitment to being alive to the possibility of contingency and experience in the moment. The other thing is , even though there’s a commitment to talking about, preserving or memorializing or at least having a memory of modes of life and experience that have passed away, there is no nostalgia. And that, to me, is a big difference between the possibility of a kind of left storytelling and the Tea Party dressing up with historically inaccurate Revolutionary costumes. So that there’s a commitment to the possibilities of the world before us, in a sensory, sensual, libidinal, neurotic way, ’cause those energies have to be harnessed for the political. And there’s a commitment to memory and having a relationship to the dead that never degenerates into the seduction of nostalgia.

·乡村

Just as with the Internet and web, people live in an endlessly extensive present moment, with collections of the present absolutely unimaginable a little while ago. I mean, enormous extension, positive and negative in this way. But it is of the instant, but it’s as if were geographic and spatial. In the contry, and in a village like Quincy, that extension is vertical, and it’s to do with time. And that’s where the dead take prop. And the idea of children is not only all the natural reasons, but also a question of that continuity, that vertical continuity.

Interesting that for a peasant, the way he reads the landscape is completely different than ours, in the sense that what we would find, like a beautiful landscape, he could find beautiful equally, but for other reasons. That’s to say, the beauty would come from the value of the work that has been put into that landscape, which has shaped that landscape. Detail reveals something of the work done of it.

In the country where you are so open, and some kind of horizon is always there, you’re never shut in. Because you are open, every season has its particularities, some of which you like. In other words, a season isn’t something that befalls you, it is something that you inhabit.

6 ) 如果回忆令人苍老,我愿意

在看完他的纪录片《观看之道》之后,被他的智慧所吸引,想更了解这个人而买了这本书——《我们在此相遇》。

看一本书,就像是远远走来一个人,你嗅到了他身上独特的气味,然后你一步步深入去了解他,被他的睿智所吸引。

就是这个老爷子,成功引起了牛叔的关注。

他年轻的时候当过画家、教过书、当过艺术批评家、写的小说还获过大奖提名。放在现在,就是大家常说的“斜杠青年”。

有人说他很激进,在纪录片《观看之道》里,他的一番言论颠覆了很多人的常识。

他吸引我的地方在于他自身独立的思考。

我们在美术馆或者纪录片里欣赏艺术作品时,约翰·伯格在纪录片里的这种批判性的眼光可以作为借鉴。大致可以归纳为:

1、摄影的普及,让绘画作品随处可见。因为观看地点的变化,我们对于画的看法也会发生变化。

伯格用裁纸刀从波提切利的名画《维纳斯与马尔斯》切割下维纳斯的头像,并宣布:脱离画幅的维纳斯头像,可以仅仅是一幅少女肖像。

2、艺术纪录片或者书本在鼓吹绘画真品如何之好。而伯格认为只有除掉围绕着艺术的虚假的神秘性和强烈的信仰感,它才会显出真相。

3、画是无声静止的,而现代人通过声音和动画篡改了画的原本意义。

不过,伯格在最后说道:“但在最后,我所说,所展示的一切,和其他通过现代复制技术展示及谈论的东西一样,必须由你自己来评判。”

在观看时,他带着你一起思考,观看完之后,他又把思考的主动权抛给你。

蒂尔达拍的这部《昆西四季》,还原了一个晚年的伯格,思维依然清晰。

从70年代开始约翰·伯格和妻子Beverly“隐居”到阿尔卑斯山脚下的昆西小镇。

他回忆起自己的父亲,眼睛里有闪烁的泪光:

“吃早饭时,他会取一只苹果,然后削皮,然后一切四份,挨个削皮,先把苹果核取出来,然后把果皮削下,然后他会把苹果放在盘子的前方给我吃。”

在院子里有去世的妻子Beverly亲手种下的树莓,是她生前最爱。他对两个年轻人说:

“我想让你们去摘树莓,摘一大碗树莓,送给你想送的人,然后,如果你们喜欢,从中取两小碗树莓,如果喜欢就加糖和奶油。然后找一张Beverly的照片,把她放在那里,然后在一旁吃树莓。因为你们的快乐会带给她快乐。”

siff2017

一部激发灵感的纪录片——画面,音乐,真的都很美,内容也属优质。但可能就是淡淡的,什么也留不下吧。Tilda的出镜有时真的是一个出戏和自恋的符号扔在那,也许大部分观众还是爱的。

#SIFF# 四季,四个切入点。风格比较混杂,但每个部分都很有洞察力。(是时候把John Berger的中文译名改回来了吧……伯杰~~~)

伯格描述夜里牛铃响,伯格儿子与Tilda乖巧的儿女围坐在一起边吃覆盆子边纪念逝去的母亲…被感动。地狱才需要团结这句话还真妙!有对影迷夫妇带着婴儿来看,婴儿很乖就咿呀见了几声,一叫爸妈就抱着他跑到最后角落。快结束时镜头扫过昆西宁静的草原、温顺的牛羊时婴儿还笑了一声,祥和的一刻

有一句台词叫“这里总有存在的意义”,很荣幸啊。感觉受到了鼓励。伟大的日常教会我们太多了,我很庆幸学到了些皮毛。刚意识到,我们被资本裹挟是从出生开始的,而非进城的那一刻。

因为对约翰伯格一点都不熟悉,而这部纪录片是以散文式的拍摄手法来完成的,每一部分都由不同的导演去完成,因此总体挺“散”的。开头那几部分看得我有点雨里雾里,但是从他们一批作家围坐在一起聚会开始,电影对我来说渐入佳境。最后面那部分还一度使我落泪。喜欢第七个人的那一段话。

我在梦里见到了我的朋友:“朋友,你是从照片里过来的吗?还是坐火车?”去世前一年的伯格爷爷还兴致大好地教17岁小女孩骑摩托车,既振奋又感动,又想到苏珊奈曼谈老年的时候说的:他们向我们展示了人可以走得多远,创造力可以持续多久,为我们树立了如何成长的榜样。

托曲珍的福看到這麼好的片兒。簡直是某種revelation moment。很好奇怎麼做出來這樣一個片子。真喜歡英國的intellectual氣質。最被夏季那段關於動物的觀點打到:十年壽命的羊,或是二十年的馬,對人類來說其實是不死的,因爲整體沒變,死去的不斷被新生的代替。

如今看依旧是温暖安心踏实的感觉,即便他已逝世。

除了对猪的部分有点难以共情,这部纪录片简直看到心里去了。一是形式上的自然灵动,一点也不拘束。二是即便在那么世外桃源的语境里它反而提醒了我伯格身上的战斗性,他始终是在激进运动和思想的前线,而无望几乎是战斗必然的历史前提。最后也是最喜欢看的是他们谈话时肢体语言里掩饰不住的专注和喜悦,都是多好的人多美妙的相遇啊。也可以用法拉奇那句来解释,“共同思考共同反抗,这本身就是一种爱的关系。”

fabulous view of image

蒂尔达念白:如果你将来到这个世界,那你最好出生七次。一次在着火的房子里,一次在冰冷的洪水中,一次在疯狂的精神病院里,一次在成熟的麦田中,一次在无人的修道院里,一次在猪圈的猪中间。这六次出生的婴儿都会哭泣,但这不够,你自己必须成为第七人。当你必须战斗才能生存,让你的敌人看到这七个人

温柔到让人心醉 看着蒂尔达切苹果 每个人简单的白描画像 农场里动物们短暂却安详的生活 大家分食红嫩的覆盆子 不知不觉就流泪了

Sheffield doc / fest Essay film it not doc actually...the most excited part is Q&A section just saw Tilda so close.

「Silence can also be incredibly communicative.」「"If you set out in this world, better be born seven times. Once in a house on fire, once in a freezing flood, once in a wild madhouse, once in a field of ripe wheat, once in an empty cloister, and once among pigs in sty. Six babes crying, not enough. You yourself must be the seventh. When you must fight to survive, let your enemies see seven." — The Seventh by Attila József」

用四個不同形式的短片展現昆西四季不同的面向。tilda控制欲這麼強,導演可能更適合她。

父辈战后创伤、人与动物面面观、左派议论与人的解放、一场昆西之行。人的思想越复杂、成就越多面,也就越难一言道尽。信息量太大,且毫无前置知识。但当你看到一个人能在对家畜抱有同情的同时,又能平静甚至巨细靡遗地谈论一场记忆中的屠宰,并且并未简单导向素食主义时,你就能管窥其思辨之丰富与立体。

犹记得他谈起父亲时眼角的湿润。这是每一个人子无法抗拒的。

看tilda跟约翰伯格唠嗑我能看一天不换台。太享受了。两人聪明又博学的人聊起政治,战争,写作,哲学,父亲,无比的轻松自然而又在某一刻深刻的让人想要掉眼泪。

金马影展上看了这部纪录片一直没有标记,一晃眼,约翰伯格就90岁生日了,一晃眼,他就悄悄离开了人世。